Difference between revisions of "User:Jhurley/sandbox"

(→Advection-Dispersion-Reaction Equation) |

(→The VI Diagnosis Toolkit Components) |

||

| (898 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | ==Assessing Vapor Intrusion (VI) Impacts in Neighborhoods with Groundwater Contaminated by Chlorinated Volatile Organic Chemicals (CVOCs)== | |

| − | + | The VI Diagnosis Toolkit<ref name="JohnsonEtAl2020">Johnson, P.C., Guo, Y., Dahlen, P., 2020. The VI Diagnosis Toolkit for Assessing Vapor Intrusion Pathways and Mitigating Impacts in Neighborhoods Overlying Dissolved Chlorinated Solvent Plumes. ESTCP Project ER-201501, Final Report. [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/a0d8bafd-c158-4742-b9fe-5f03d002af71 Project Website] [[Media: ER-201501.pdf | Final Report.pdf]]</ref> is a set of tools that can be used individually or in combination to assess vapor intrusion (VI) impacts at one or more buildings overlying regional-scale dissolved chlorinated solvent-impacted groundwater plumes. The strategic use of these tools can lead to confident and efficient neighborhood-scale VI pathway assessments. | |

| − | |||

<div style="float:right;margin:0 0 2em 2em;">__TOC__</div> | <div style="float:right;margin:0 0 2em 2em;">__TOC__</div> | ||

'''Related Article(s):''' | '''Related Article(s):''' | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | ''' | + | *[[Vapor Intrusion (VI)]] |

| − | * | + | *[[Vapor Intrusion – Sewers and Utility Tunnels as Preferential Pathways]] |

| − | * | + | |

| + | '''Contributor(s):''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Paul C. Johnson, Ph.D. | ||

| + | *Paul Dahlen, Ph.D. | ||

| + | *Yuanming Guo, Ph.D. | ||

'''Key Resource(s):''' | '''Key Resource(s):''' | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | + | *The VI Diagnosis Toolkit for Assessing Vapor Intrusion Pathways and Impacts in Neighborhoods Overlying Dissolved Chlorinated Solvent Plumes, ESTCP Project ER-201501, Final Report<ref name="JohnsonEtAl2020"/> |

| − | [[ | + | |

| − | Groundwater | + | *CPM Test Guidelines: Use of Controlled Pressure Method Testing for Vapor Intrusion Pathway Assessment, ESTCP Project ER-201501, Technical Report<ref name="JohnsonEtAl2021">Johnson, P.C., Guo, Y., Dahlen, P., 2021. CPM Test Guidelines: Use of Controlled Pressure Method Testing for Vapor Intrusion Pathway Assessment. ESTCP ER-201501, Technical Report. [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/a0d8bafd-c158-4742-b9fe-5f03d002af71 Project Website] [[Media: ER-201501_Technical_Report.pdf | Technical_Report.pdf]]</ref> |

| + | |||

| + | *VI Diagnosis Toolkit User Guide, ESTCP Project ER-201501<ref name="JohnsonEtAl2022">Johnson, P.C., Guo, Y., and Dahlen, P., 2022. VI Diagnosis Toolkit User Guide, ESTCP ER-201501, User Guide. [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/a0d8bafd-c158-4742-b9fe-5f03d002af71 Project Website] [[Media: ER-201501_User_Guide.pdf | User_Guide.pdf]]</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Introduction== | ||

| + | Most federal, state, and local regulatory guidance for assessing and mitigating the [[Vapor Intrusion (VI) | vapor intrusion]] pathway reflects USEPA’s ''Technical Guide for Assessing and Mitigating the Vapor Intrusion Pathway from Subsurface Vapor Sources to Indoor Air''<ref name="USEPA2015">USEPA, 2015. OSWER Technical Guide for Assessing and Mitigating the Vapor Intrusion Pathway from Subsurface Vapor Sources to Indoor Air. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response, OSWER Publication No. 9200.2-154, 267 pages. [https://www.epa.gov/vaporintrusion/technical-guide-assessing-and-mitigating-vapor-intrusion-pathway-subsurface-vapor USEPA Website] [[Media: USEPA2015.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref>. The paradigm outlined by that guidance includes: 1) a preliminary and mostly qualitative analysis that looks for site conditions that suggest vapor intrusion might occur (e.g., the presence of vapor-forming chemicals in close proximity to buildings); 2) a multi-step and more detailed quantitative screening analysis that involves site-specific data collection and their comparison to screening levels to identify buildings of potential VI concern; and 3) selection and design of mitigation systems or continued monitoring, as needed. With respect to (2), regulatory guidance typically recommends consideration of “multiple lines of evidence” in decision-making<ref name="USEPA2015"/><ref>NJDEP, 2021. Vapor Intrusion Technical Guidance, Version 5.0. New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, Trenton, NJ. [https://dep.nj.gov/srp/guidance/vapor-intrusion/vig/ Website] [[Media: NJDEP2021.pdf | Guidance Document.pdf]]</ref>, with typical lines-of-evidence being groundwater, soil gas, sub-slab soil gas, and/or indoor air concentrations. Of those, soil gas measurements and/or measured short-term indoor air concentrations can be weighted heavily, and therefore decision making might not be completed without them. Effective evaluation of VI risk from sub-slab and/or soil gas measurements would require an unknown building-specific attenuation factor, but there is also uncertainty as to whether or not indoor air data is representative of maximum and/or long-term average indoor concentrations. Indoor air data can be confounded by indoor contaminant sources because the number of samples is typically small, indoor concentrations can vary with time, and because a number of household products can emit the chemicals being measured. When conducting VI pathway assessments in neighborhoods where it is impractical to assess all buildings, the EPA recommends following a “worst first” investigational approach. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The limitations of this approach, as practiced, are the following: | ||

| + | *Decisions are rarely made without indoor air data and generally, seasonal sampling is required, delaying decision-making. | ||

| + | *The collection of a robust indoor air data set that adequately characterizes long-term indoor air concentrations could take years given the typical frequency of data collection and the most common methods of sample collection (e.g., 24-hour samples). Therefore, indoor air sampling might continue indefinitely at some sites. | ||

| + | *The “worst first” buildings might not be identified correctly by the logic outlined in USEPA’s 2015 guidance and the most impacted buildings might not even be located over a groundwater plume. Recent studies have shown [[Vapor Intrusion – Sewers and Utility Tunnels as Preferential Pathways |VI impacts in homes as a result of sewer and other subsurface piping connections]], which are not explicitly considered nor easily characterized through conventional VI pathway assessment<ref> Beckley, L, McHugh, T., 2020. A Conceptual Model for Vapor Intrusion from Groundwater Through Sewer Lines. Science of the Total Environment, 698, Article 134283. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134283 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134283] [[Media: BeckleyMcHugh2020.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref><ref name="GuoEtAl2015">Guo, Y., Holton, C., Luo, H., Dahlen, P., Gorder, K., Dettenmaier, E., Johnson, P.C., 2015. Identification of Alternative Vapor Intrusion Pathways Using Controlled Pressure Testing, Soil Gas Monitoring, and Screening Model Calculations. Environmental Science and Technology, 49(22), pp. 13472–13482. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.5b03564 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b03564]</ref><ref name="McHughEtAl2017">McHugh, T., Beckley, L., Sullivan, T., Lutes, C., Truesdale, R., Uppencamp, R., Cosky, B., Zimmerman, J., Schumacher, B., 2017. Evidence of a Sewer Vapor Transport Pathway at the USEPA Vapor Intrusion Research Duplex. Science of the Total Environment, pp. 598, 772-779. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.04.135 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.04.135] [[Media: McHughEtAl2017.pdf | Open Access Manuscipt]]</ref><ref name="McHughBeckley2018">McHugh, T., Beckley, L., 2018. Sewers and Utility Tunnels as Preferential Pathways for Volatile Organic Compound Migration into Buildings: Risk Factors and Investigation Protocol. ESTCP ER-201505, Final Report. [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/f12abf80-5273-4220-b09a-e239d0188421 Project Website] [[Media: 2018b-McHugh-ER-201505_Conceptual_Model.pdf | Final Report.pdf]]</ref><ref name="RiisEtAl2010">Riis, C., Hansen, M.H., Nielsen, H.H., Christensen, A.G., Terkelsen, M., 2010. Vapor Intrusion through Sewer Systems: Migration Pathways of Chlorinated Solvents from Groundwater to Indoor Air. Seventh International Conference on Remediation of Chlorinated and Recalcitrant Compounds, May, Monterey, CA. Battelle Memorial Institute. ISBN 978-0-9819730-2-9. [https://www.battelle.org/conferences/battelle-conference-proceedings Website] [[Media: 2010-Riis-Migratioin_pathways_of_Chlorinated_Solvents.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref>. | ||

| + | *The presumptive remedy for VI mitigation (sub-slab depressurization) may not be effective for all VI scenarios (e.g., those involving vapor migration to indoor spaces via sewer connections). | ||

| + | |||

| + | The '''VI Diagnosis Toolkit''' components were developed considering these limitations as well as more recent knowledge gained through research, development, and validation projects funded by SERDP and ESTCP. | ||

| − | == | + | ==The VI Diagnosis Toolkit Components== |

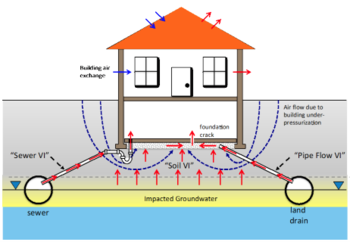

| − | + | [[File:DahlenFig1.png|thumb|350px|Figure 1. Vapor intrusion pathway conceptualization considering “alternate VI pathways”, including “pipe flow | |

| − | | | + | VI” and “sewer VI” pathways<ref name="JohnsonEtAl2020"/>.]] |

| − | + | The primary components of the VI Diagnosis Toolkit and their uses include: | |

| − | + | *'''External VI source strength screening''' to identify buildings most likely to be impacted by VI at levels warranting building-specific testing. | |

| − | + | *'''Indoor air source screening''' to locate and remove indoor air sources that might confound building specific VI pathway assessment. | |

| − | + | *'''Controlled pressurization method (CPM)''' testing to quickly (in a few days or less) measure the worst-case indoor air impact likely to be caused by VI under natural conditions in specific buildings. CPM tests can also be used to identify the presence of indoor air sources and diagnose active VI pathways. | |

| − | + | *'''Passive indoor sampling''' for determining long-term average indoor air concentrations under natural VI conditions and/or for verifying mitigation system effectiveness in buildings that warrant VI mitigation. | |

| − | + | *'''Comprehensive VI conceptual model development and refinement''' to ensure that appropriate monitoring, investigation, and mitigation strategies are being selected (Figure 1). | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Expanded discussions for each of these are given below. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | '''External VI source strength screening''' identifies those buildings that warrant more intrusive building-specific assessments, using data collected exterior to the buildings. The use of groundwater and/or soil gas concentration data for building screening has been part of VI pathway assessments for some time and their use is discussed in many regulatory guidance documents. Typically, the measured concentrations are compared to relevant screening levels derived via modeling or empirical analyses from indoor air concentrations of concern. | |

| − | + | More recently it has been discovered that VI impacts can occur via sewer and other subsurface piping connections in areas where vapor migration through the soil would not be expected to be significant, and this could also occur in buildings that do not sit over contaminated groundwater<ref name="RiisEtAl2010"/><ref name="GuoEtAl2015"/><ref name="McHughEtAl2017"/><ref name="McHughBeckley2018"/>. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Therefore, in addition to groundwater and soil gas sampling, external data collection that includes and extends beyond the area of concern should include manhole vapor sampling (e.g., sanitary sewer, storm sewer, land-drain). Video surveys from sanitary sewers, storm sewers, and/or land-drains can also be used to identify areas of groundwater leakage into utility corridors and lateral connections to buildings that are conduits for vapor transport. During these investigations, it is important to recognize that utility corridors can transmit both impacted water and vapors beyond groundwater plume boundaries, so extending investigations into areas adjacent to groundwater plume boundaries is necessary. | |

| − | + | Using projected indoor air concentrations from modeling and empirical data analyses, and distance screening approaches, external source screening can identify areas and buildings that can be ruled out, or conversely, those that warrant building-specific testing. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Demonstration of neighborhood-scale external VI source screening using groundwater, depth, sewer, land drain, and video data is documented in the ER-201501 final report<ref name="JohnsonEtAl2020"/>. | |

| − | [[ | + | '''Indoor air source screening''' seeks to locate and remove indoor air sources<ref>Doucette, W.J., Hall, A.J., Gorder, K.A., 2010. Emissions of 1,2-Dichloroethane from Holiday Decorations as a Source of Indoor Air Contamination. Ground Water Monitoring and Remediation, 30(1), pp. 67-73. [https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6592.2009.01267.x doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6592.2009.01267.x] </ref> that might confound building specific VI pathway assessment. Visual inspections and written surveys might or might not identify significant indoor air sources, so these should be complemented with use of portable analytical instruments<ref>McHugh, T., Kuder, T., Fiorenza, S., Gorder, K., Dettenmaier, E., Philp, P., 2011. Application of CSIA to Distinguish Between Vapor Intrusion and Indoor Sources of VOCs. Environmental Science and Technology, 45(14), pp. 5952-5958. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es200988d doi: 10.1021/es200988d]</ref><ref name="BeckleyEtAl2014">Beckley, L., Gorder, K., Dettenmaier, E., Rivera-Duarte, I., McHugh, T., 2014. On-Site Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry (GC/MS) Analysis to Streamline Vapor Intrusion Investigations. Environmental Forensics, 15(3), pp. 234–243. [https://doi.org/10.1080/15275922.2014.930941 doi: 10.1080/15275922.2014.930941]</ref>. |

| − | + | The advantage of portable analytical tools is that they allow practitioners to expeditiously test indoor air concentrations under natural conditions in each room of the building. Concentrations in any room in excess of relevant screening levels trigger more sampling in that room to identify if an indoor source is present in that room. Removal of a suspected source and subsequent room testing can identify if that object or product was the source of the previously measured concentrations. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | '''Building-specific controlled pressurization method (CPM) testing''' directly measures the worst case indoor air impact, but it can also be used to determine contributing VI pathways and to identify indoor air sources<ref>McHugh, T.E., Beckley, L., Bailey, D., Gorder, K., Dettenmaier, E., Rivera-Duarte, I., Brock, S., MacGregor, I.C., 2012. Evaluation of Vapor Intrusion Using Controlled Building Pressure. Environmental Science and Technology, 46(9), pp. 4792–4799. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es204483g doi: 10.1021/es204483g]</ref><ref name="BeckleyEtAl2014"/><ref name="GuoEtAl2015"/><ref name="HoltonEtAl2015">Holton, C., Guo, Y., Luo, H., Dahlen, P., Gorder, K., Dettenmaier, E., Johnson, P.C., 2015. Long-Term Evaluation of the Controlled Pressure Method for Assessment of the Vapor Intrusion Pathway. Environmental Science and Technology, 49(4), pp. 2091–2098. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es5052342 doi: 10.1021/es5052342]</ref><ref name="JohnsonEtAl2020"/><ref name="GuoEtAl2020a">Guo, Y., Dahlen, P., Johnson, P.C., 2020a. Development and Validation of a Controlled Pressure Method Test Protocol for Vapor Intrusion Pathway Assessment. Environmental Science and Technology, 54(12), pp. 7117-7125. [https://dx.doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.0c00811 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c00811]</ref>. In CPM testing, blowers/fans installed in a doorway(s) or window(s) are set-up to exhaust indoor air to outdoor, which causes the building to be under pressurized relative to the atmosphere. This induces air movement from the subsurface into the test building via openings in the foundation and/or subsurface piping networks with or without direct connections to indoor air. This is similar to what happens intermittently under natural conditions when wind, indoor-outdoor temperature differences, and/or use of appliances that exhaust air from the structure (e.g. dryer exhaust) create an under-pressurized building condition. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The blowers/fans can also be used to blow outdoor air into the building, thereby creating a building over-pressurization condition. A positive pressure difference CPM test suppresses VI pathways; therefore, chemicals detected in indoor air above outdoor air concentrations during this condition are attributed to indoor contaminant sources which facilitates the identification of any such indoor air sources. | |

| − | + | Data collected during CPM testing, when combined with screening level VI modeling, can be used to identify which VI chemical migration pathways are significant contributors to indoor air impacts<ref name="GuoEtAl2015"/>. CPM testing guidelines were developed and validated under ESTCP Project ER-201501<ref name="GuoEtAl2020a"/><ref name="JohnsonEtAl2021"/>. | |

| − | + | '''Passive samplers''' can be used to measure long term average indoor air concentrations under natural conditions and during VI mitigation system operation. They will provide more confident assessment of long term average concentrations than an infrequent sequence of short term grab samples. Long term average concentrations can also be determined by long term active sampling (e.g., by slowly pulling air through a thermal desorption (TD) tube). However, passive sampling has the advantage that additional equipment and expertise is not required for sampler deployment and recovery. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Use of passive samplers in indoor air under time-varying concentration conditions was demonstrated and validated by comparing against intensive active sampling in ESTCP Project ER-201501<ref name="JohnsonEtAl2020"/><ref name="GuoEtAl2021">Guo, Y., O’Neill, H., Dahlen, P., and Johnson, P.C. 2021. Evaluation of Passive Diffusive-Adsorptive Samplers for Use in Assessing Time-Varying Indoor Air Impacts Resulting from Vapor Intrusion. Groundwater Monitoring and Remediation, 42(1), pp. 38-49. [https://doi.org/10.1111/gwmr.12481 doi: 10.1111/12481]</ref>. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | :: | ||

| − | |||

| − | The | + | The purpose of maintaining an evergreen '''comprehensive VI conceptual model''' is to ensure that the most complete and up-to-date understanding of the site is informing decisions related to future sampling, data interpretation, and the need for and design of mitigation systems. The VI conceptual model can also serve as an effective communication tool in stakeholder discussions. |

| − | + | Use of these tools for residential neighborhoods and in non-residential buildings overlying chlorinated solvent groundwater plumes is documented comprehensively in a series of peer reviewed articles<ref name="JohnsonEtAl2020"/><ref name="JohnsonEtAl2021"/><ref name="JohnsonEtAl2022"/><ref name="GuoEtAl2015"/><ref name="GuoEtAl2020a"/><ref name="GuoEtAl2020b">Guo, Y., Dahlen, P., Johnson, P.C. 2020b. Temporal variability of chlorinated volatile organic compound vapor concentrations in a residential sewer and land drain system overlying a dilute groundwater plume. Science of the Total Environment, 702, Article 134756. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134756 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134756] [[Media: GuoEtAl2020b.pdf | Open Access Manuscript]]</ref><ref name="GuoEtAl2021"/><ref name="HoltonEtAl2015"/>. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | :: | ||

| − | + | ==Summary== | |

| + | In summary, the VI Diagnosis Toolkit provides a set of tools that can lead to quicker, more confident, and more cost effective neighborhood-scale VI pathway and impact assessments. Toolkit components and their use can complement conventional methods for assessing and mitigating the vapor intrusion pathway. | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | + | <references /> | |

| − | <references/> | ||

==See Also== | ==See Also== | ||

| − | *[ | + | *[https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4000681 Evaluation of Radon and Building Pressure Differences as Environmental Indicators for Vapor Intrusion Assessment] |

| − | + | *[https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/es4024767 Temporal Variability of Indoor Air Concentrations under Natural Conditions in a House Overlying a Dilute Chlorinated Solvent Groundwater Plume] | |

| − | *[https:// | + | *[https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/e0d00662-c333-4560-8ae7-60f20b0e714b Integrated Field-Scale, Lab-Scale, and Modeling Studies for Improving Our Ability to Assess the Groundwater to Indoor Air Pathway at Chlorinated Solvent Impacted Sites] |

| − | |||

| − | *[https:// | ||

Revision as of 22:20, 18 July 2024

Assessing Vapor Intrusion (VI) Impacts in Neighborhoods with Groundwater Contaminated by Chlorinated Volatile Organic Chemicals (CVOCs)

The VI Diagnosis Toolkit[1] is a set of tools that can be used individually or in combination to assess vapor intrusion (VI) impacts at one or more buildings overlying regional-scale dissolved chlorinated solvent-impacted groundwater plumes. The strategic use of these tools can lead to confident and efficient neighborhood-scale VI pathway assessments.

Related Article(s):

Contributor(s):

- Paul C. Johnson, Ph.D.

- Paul Dahlen, Ph.D.

- Yuanming Guo, Ph.D.

Key Resource(s):

- The VI Diagnosis Toolkit for Assessing Vapor Intrusion Pathways and Impacts in Neighborhoods Overlying Dissolved Chlorinated Solvent Plumes, ESTCP Project ER-201501, Final Report[1]

- CPM Test Guidelines: Use of Controlled Pressure Method Testing for Vapor Intrusion Pathway Assessment, ESTCP Project ER-201501, Technical Report[2]

- VI Diagnosis Toolkit User Guide, ESTCP Project ER-201501[3]

Introduction

Most federal, state, and local regulatory guidance for assessing and mitigating the vapor intrusion pathway reflects USEPA’s Technical Guide for Assessing and Mitigating the Vapor Intrusion Pathway from Subsurface Vapor Sources to Indoor Air[4]. The paradigm outlined by that guidance includes: 1) a preliminary and mostly qualitative analysis that looks for site conditions that suggest vapor intrusion might occur (e.g., the presence of vapor-forming chemicals in close proximity to buildings); 2) a multi-step and more detailed quantitative screening analysis that involves site-specific data collection and their comparison to screening levels to identify buildings of potential VI concern; and 3) selection and design of mitigation systems or continued monitoring, as needed. With respect to (2), regulatory guidance typically recommends consideration of “multiple lines of evidence” in decision-making[4][5], with typical lines-of-evidence being groundwater, soil gas, sub-slab soil gas, and/or indoor air concentrations. Of those, soil gas measurements and/or measured short-term indoor air concentrations can be weighted heavily, and therefore decision making might not be completed without them. Effective evaluation of VI risk from sub-slab and/or soil gas measurements would require an unknown building-specific attenuation factor, but there is also uncertainty as to whether or not indoor air data is representative of maximum and/or long-term average indoor concentrations. Indoor air data can be confounded by indoor contaminant sources because the number of samples is typically small, indoor concentrations can vary with time, and because a number of household products can emit the chemicals being measured. When conducting VI pathway assessments in neighborhoods where it is impractical to assess all buildings, the EPA recommends following a “worst first” investigational approach.

The limitations of this approach, as practiced, are the following:

- Decisions are rarely made without indoor air data and generally, seasonal sampling is required, delaying decision-making.

- The collection of a robust indoor air data set that adequately characterizes long-term indoor air concentrations could take years given the typical frequency of data collection and the most common methods of sample collection (e.g., 24-hour samples). Therefore, indoor air sampling might continue indefinitely at some sites.

- The “worst first” buildings might not be identified correctly by the logic outlined in USEPA’s 2015 guidance and the most impacted buildings might not even be located over a groundwater plume. Recent studies have shown VI impacts in homes as a result of sewer and other subsurface piping connections, which are not explicitly considered nor easily characterized through conventional VI pathway assessment[6][7][8][9][10].

- The presumptive remedy for VI mitigation (sub-slab depressurization) may not be effective for all VI scenarios (e.g., those involving vapor migration to indoor spaces via sewer connections).

The VI Diagnosis Toolkit components were developed considering these limitations as well as more recent knowledge gained through research, development, and validation projects funded by SERDP and ESTCP.

The VI Diagnosis Toolkit Components

The primary components of the VI Diagnosis Toolkit and their uses include:

- External VI source strength screening to identify buildings most likely to be impacted by VI at levels warranting building-specific testing.

- Indoor air source screening to locate and remove indoor air sources that might confound building specific VI pathway assessment.

- Controlled pressurization method (CPM) testing to quickly (in a few days or less) measure the worst-case indoor air impact likely to be caused by VI under natural conditions in specific buildings. CPM tests can also be used to identify the presence of indoor air sources and diagnose active VI pathways.

- Passive indoor sampling for determining long-term average indoor air concentrations under natural VI conditions and/or for verifying mitigation system effectiveness in buildings that warrant VI mitigation.

- Comprehensive VI conceptual model development and refinement to ensure that appropriate monitoring, investigation, and mitigation strategies are being selected (Figure 1).

Expanded discussions for each of these are given below.

External VI source strength screening identifies those buildings that warrant more intrusive building-specific assessments, using data collected exterior to the buildings. The use of groundwater and/or soil gas concentration data for building screening has been part of VI pathway assessments for some time and their use is discussed in many regulatory guidance documents. Typically, the measured concentrations are compared to relevant screening levels derived via modeling or empirical analyses from indoor air concentrations of concern.

More recently it has been discovered that VI impacts can occur via sewer and other subsurface piping connections in areas where vapor migration through the soil would not be expected to be significant, and this could also occur in buildings that do not sit over contaminated groundwater[10][7][8][9].

Therefore, in addition to groundwater and soil gas sampling, external data collection that includes and extends beyond the area of concern should include manhole vapor sampling (e.g., sanitary sewer, storm sewer, land-drain). Video surveys from sanitary sewers, storm sewers, and/or land-drains can also be used to identify areas of groundwater leakage into utility corridors and lateral connections to buildings that are conduits for vapor transport. During these investigations, it is important to recognize that utility corridors can transmit both impacted water and vapors beyond groundwater plume boundaries, so extending investigations into areas adjacent to groundwater plume boundaries is necessary.

Using projected indoor air concentrations from modeling and empirical data analyses, and distance screening approaches, external source screening can identify areas and buildings that can be ruled out, or conversely, those that warrant building-specific testing.

Demonstration of neighborhood-scale external VI source screening using groundwater, depth, sewer, land drain, and video data is documented in the ER-201501 final report[1].

Indoor air source screening seeks to locate and remove indoor air sources[11] that might confound building specific VI pathway assessment. Visual inspections and written surveys might or might not identify significant indoor air sources, so these should be complemented with use of portable analytical instruments[12][13].

The advantage of portable analytical tools is that they allow practitioners to expeditiously test indoor air concentrations under natural conditions in each room of the building. Concentrations in any room in excess of relevant screening levels trigger more sampling in that room to identify if an indoor source is present in that room. Removal of a suspected source and subsequent room testing can identify if that object or product was the source of the previously measured concentrations.

Building-specific controlled pressurization method (CPM) testing directly measures the worst case indoor air impact, but it can also be used to determine contributing VI pathways and to identify indoor air sources[14][13][7][15][1][16]. In CPM testing, blowers/fans installed in a doorway(s) or window(s) are set-up to exhaust indoor air to outdoor, which causes the building to be under pressurized relative to the atmosphere. This induces air movement from the subsurface into the test building via openings in the foundation and/or subsurface piping networks with or without direct connections to indoor air. This is similar to what happens intermittently under natural conditions when wind, indoor-outdoor temperature differences, and/or use of appliances that exhaust air from the structure (e.g. dryer exhaust) create an under-pressurized building condition.

The blowers/fans can also be used to blow outdoor air into the building, thereby creating a building over-pressurization condition. A positive pressure difference CPM test suppresses VI pathways; therefore, chemicals detected in indoor air above outdoor air concentrations during this condition are attributed to indoor contaminant sources which facilitates the identification of any such indoor air sources.

Data collected during CPM testing, when combined with screening level VI modeling, can be used to identify which VI chemical migration pathways are significant contributors to indoor air impacts[7]. CPM testing guidelines were developed and validated under ESTCP Project ER-201501[16][2].

Passive samplers can be used to measure long term average indoor air concentrations under natural conditions and during VI mitigation system operation. They will provide more confident assessment of long term average concentrations than an infrequent sequence of short term grab samples. Long term average concentrations can also be determined by long term active sampling (e.g., by slowly pulling air through a thermal desorption (TD) tube). However, passive sampling has the advantage that additional equipment and expertise is not required for sampler deployment and recovery.

Use of passive samplers in indoor air under time-varying concentration conditions was demonstrated and validated by comparing against intensive active sampling in ESTCP Project ER-201501[1][17].

The purpose of maintaining an evergreen comprehensive VI conceptual model is to ensure that the most complete and up-to-date understanding of the site is informing decisions related to future sampling, data interpretation, and the need for and design of mitigation systems. The VI conceptual model can also serve as an effective communication tool in stakeholder discussions.

Use of these tools for residential neighborhoods and in non-residential buildings overlying chlorinated solvent groundwater plumes is documented comprehensively in a series of peer reviewed articles[1][2][3][7][16][18][17][15].

Summary

In summary, the VI Diagnosis Toolkit provides a set of tools that can lead to quicker, more confident, and more cost effective neighborhood-scale VI pathway and impact assessments. Toolkit components and their use can complement conventional methods for assessing and mitigating the vapor intrusion pathway.

References

- ^ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Johnson, P.C., Guo, Y., Dahlen, P., 2020. The VI Diagnosis Toolkit for Assessing Vapor Intrusion Pathways and Mitigating Impacts in Neighborhoods Overlying Dissolved Chlorinated Solvent Plumes. ESTCP Project ER-201501, Final Report. Project Website Final Report.pdf

- ^ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Johnson, P.C., Guo, Y., Dahlen, P., 2021. CPM Test Guidelines: Use of Controlled Pressure Method Testing for Vapor Intrusion Pathway Assessment. ESTCP ER-201501, Technical Report. Project Website Technical_Report.pdf

- ^ 3.0 3.1 Johnson, P.C., Guo, Y., and Dahlen, P., 2022. VI Diagnosis Toolkit User Guide, ESTCP ER-201501, User Guide. Project Website User_Guide.pdf

- ^ 4.0 4.1 USEPA, 2015. OSWER Technical Guide for Assessing and Mitigating the Vapor Intrusion Pathway from Subsurface Vapor Sources to Indoor Air. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response, OSWER Publication No. 9200.2-154, 267 pages. USEPA Website Report.pdf

- ^ NJDEP, 2021. Vapor Intrusion Technical Guidance, Version 5.0. New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, Trenton, NJ. Website Guidance Document.pdf

- ^ Beckley, L, McHugh, T., 2020. A Conceptual Model for Vapor Intrusion from Groundwater Through Sewer Lines. Science of the Total Environment, 698, Article 134283. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134283 Open Access Article

- ^ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Guo, Y., Holton, C., Luo, H., Dahlen, P., Gorder, K., Dettenmaier, E., Johnson, P.C., 2015. Identification of Alternative Vapor Intrusion Pathways Using Controlled Pressure Testing, Soil Gas Monitoring, and Screening Model Calculations. Environmental Science and Technology, 49(22), pp. 13472–13482. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b03564

- ^ 8.0 8.1 McHugh, T., Beckley, L., Sullivan, T., Lutes, C., Truesdale, R., Uppencamp, R., Cosky, B., Zimmerman, J., Schumacher, B., 2017. Evidence of a Sewer Vapor Transport Pathway at the USEPA Vapor Intrusion Research Duplex. Science of the Total Environment, pp. 598, 772-779. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.04.135 Open Access Manuscipt

- ^ 9.0 9.1 McHugh, T., Beckley, L., 2018. Sewers and Utility Tunnels as Preferential Pathways for Volatile Organic Compound Migration into Buildings: Risk Factors and Investigation Protocol. ESTCP ER-201505, Final Report. Project Website Final Report.pdf

- ^ 10.0 10.1 Riis, C., Hansen, M.H., Nielsen, H.H., Christensen, A.G., Terkelsen, M., 2010. Vapor Intrusion through Sewer Systems: Migration Pathways of Chlorinated Solvents from Groundwater to Indoor Air. Seventh International Conference on Remediation of Chlorinated and Recalcitrant Compounds, May, Monterey, CA. Battelle Memorial Institute. ISBN 978-0-9819730-2-9. Website Report.pdf

- ^ Doucette, W.J., Hall, A.J., Gorder, K.A., 2010. Emissions of 1,2-Dichloroethane from Holiday Decorations as a Source of Indoor Air Contamination. Ground Water Monitoring and Remediation, 30(1), pp. 67-73. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6592.2009.01267.x

- ^ McHugh, T., Kuder, T., Fiorenza, S., Gorder, K., Dettenmaier, E., Philp, P., 2011. Application of CSIA to Distinguish Between Vapor Intrusion and Indoor Sources of VOCs. Environmental Science and Technology, 45(14), pp. 5952-5958. doi: 10.1021/es200988d

- ^ 13.0 13.1 Beckley, L., Gorder, K., Dettenmaier, E., Rivera-Duarte, I., McHugh, T., 2014. On-Site Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry (GC/MS) Analysis to Streamline Vapor Intrusion Investigations. Environmental Forensics, 15(3), pp. 234–243. doi: 10.1080/15275922.2014.930941

- ^ McHugh, T.E., Beckley, L., Bailey, D., Gorder, K., Dettenmaier, E., Rivera-Duarte, I., Brock, S., MacGregor, I.C., 2012. Evaluation of Vapor Intrusion Using Controlled Building Pressure. Environmental Science and Technology, 46(9), pp. 4792–4799. doi: 10.1021/es204483g

- ^ 15.0 15.1 Holton, C., Guo, Y., Luo, H., Dahlen, P., Gorder, K., Dettenmaier, E., Johnson, P.C., 2015. Long-Term Evaluation of the Controlled Pressure Method for Assessment of the Vapor Intrusion Pathway. Environmental Science and Technology, 49(4), pp. 2091–2098. doi: 10.1021/es5052342

- ^ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Guo, Y., Dahlen, P., Johnson, P.C., 2020a. Development and Validation of a Controlled Pressure Method Test Protocol for Vapor Intrusion Pathway Assessment. Environmental Science and Technology, 54(12), pp. 7117-7125. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c00811

- ^ 17.0 17.1 Guo, Y., O’Neill, H., Dahlen, P., and Johnson, P.C. 2021. Evaluation of Passive Diffusive-Adsorptive Samplers for Use in Assessing Time-Varying Indoor Air Impacts Resulting from Vapor Intrusion. Groundwater Monitoring and Remediation, 42(1), pp. 38-49. doi: 10.1111/12481

- ^ Guo, Y., Dahlen, P., Johnson, P.C. 2020b. Temporal variability of chlorinated volatile organic compound vapor concentrations in a residential sewer and land drain system overlying a dilute groundwater plume. Science of the Total Environment, 702, Article 134756. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134756 Open Access Manuscript

See Also

- Evaluation of Radon and Building Pressure Differences as Environmental Indicators for Vapor Intrusion Assessment

- Temporal Variability of Indoor Air Concentrations under Natural Conditions in a House Overlying a Dilute Chlorinated Solvent Groundwater Plume

- Integrated Field-Scale, Lab-Scale, and Modeling Studies for Improving Our Ability to Assess the Groundwater to Indoor Air Pathway at Chlorinated Solvent Impacted Sites