User:Jhurley/sandbox

Assessing Vapor Intrusion (VI) Impacts in Neighborhoods with Groundwater Contaminated by Chlorinated Volatile Organic Chemicals (CVOCs)

The VI Diagnosis Toolkit[1] is a set of tools that can be used individually or in combination to assess vapor intrusion (VI) impacts at one or more buildings overlying regional-scale dissolved chlorinated solvent-impacted groundwater plumes. The strategic use of these tools can lead to confident and efficient neighborhood-scale VI pathway assessments.

Related Article(s):

Contributor(s):

- Paul C. Johnson, Ph.D.

- Paul Dahlen, Ph.D.

- Yuanming Guo, Ph.D.

Key Resource(s):

- The VI Diagnosis Toolkit for Assessing Vapor Intrusion Pathways and Impacts in Neighborhoods Overlying Dissolved Chlorinated Solvent Plumes, ESTCP Project ER-201501, Final Report[1]

- CPM Test Guidelines: Use of Controlled Pressure Method Testing for Vapor Intrusion Pathway Assessment, ESTCP Project ER-201501, Technical Report[2]

- VI Diagnosis Toolkit User Guide, ESTCP Project ER-201501[3]

Introduction

Most federal, state, and local regulatory guidance for assessing and mitigating the vapor intrusion pathway reflects USEPA’s Technical Guide for Assessing and Mitigating the Vapor Intrusion Pathway from Subsurface Vapor Sources to Indoor Air[4]. The paradigm outlined by that guidance includes: 1) a preliminary and mostly qualitative analysis that looks for site conditions that suggest vapor intrusion might occur (e.g., the presence of vapor-forming chemicals in close proximity to buildings); 2) a multi-step and more detailed quantitative screening analysis that involves site-specific data collection and their comparison to screening levels to identify buildings of potential VI concern; and 3) selection and design of mitigation systems or continued monitoring, as needed. With respect to (2), regulatory guidance typically recommends consideration of “multiple lines of evidence” in decision-making[4][5], with typical lines-of-evidence being groundwater, soil gas, sub-slab soil gas, and/or indoor air concentrations. Of those, soil gas measurements and/or measured short-term indoor air concentrations can be weighted heavily, and therefore decision making might not be completed without them. Effective evaluation of VI risk from sub-slab and/or soil gas measurements would require an unknown building-specific attenuation factor, but there is also uncertainty as to whether or not indoor air data is representative of maximum and/or long-term average indoor concentrations. Indoor air data can be confounded by indoor contaminant sources because the number of samples is typically small, indoor concentrations can vary with time, and because a number of household products can emit the chemicals being measured. When conducting VI pathway assessments in neighborhoods where it is impractical to assess all buildings, the EPA recommends following a “worst first” investigational approach.

The limitations of this approach, as practiced, are the following:

- Decisions are rarely made without indoor air data and generally, seasonal sampling is required, delaying decision-making.

- The collection of a robust indoor air data set that adequately characterizes long-term indoor air concentrations could take years given the typical frequency of data collection and the most common methods of sample collection (e.g., 24-hour samples). Therefore, indoor air sampling might continue indefinitely at some sites.

- The “worst first” buildings might not be identified correctly by the logic outlined in USEPA’s 2015 guidance and the most impacted buildings might not even be located over a groundwater plume. Recent studies have shown VI impacts in homes as a result of sewer and other subsurface piping connections, which are not explicitly considered nor easily characterized through conventional VI pathway assessment[6][7][8][9][10].

- The presumptive remedy for VI mitigation (sub-slab depressurization) may not be effective for all VI scenarios (e.g., those involving vapor migration to indoor spaces via sewer connections).

The VI Diagnosis Toolkit components were developed considering these limitations as well as more recent knowledge gained through research, development, and validation projects funded by SERDP and ESTCP.

The VI Diagnosis Toolkit Components

The primary components of the VI Diagnosis Toolkit and their uses include:

- External VI source strength screening to identify buildings most likely to be impacted by VI at levels warranting building-specific testing.

- Indoor air source screening to locate and remove indoor air sources that might confound building specific VI pathway assessment.

- Controlled pressurization method (CPM) testing to quickly (in a few days or less) measure the worst-case indoor air impact likely to be caused by VI under natural conditions in specific buildings. CPM tests can also be used to identify the presence of indoor air sources and diagnose active VI pathways.

- Passive indoor sampling for determining long-term average indoor air concentrations under natural VI conditions and/or for verifying mitigation system effectiveness in buildings that warrant VI mitigation.

- Comprehensive VI conceptual model development and refinement to ensure that appropriate monitoring, investigation, and mitigation strategies are being selected.

Expanded discussions for each of these are given below.

External VI source strength screening identifies those buildings that warrant more intrusive building-specific assessments, using data collected exterior to the buildings. The use of groundwater and/or soil gas concentration data for building screening has been part of VI pathway assessments for some time and their use is discussed in many regulatory guidance documents. Typically, the measured concentrations are compared to relevant screening levels derived via modeling or empirical analyses from indoor air concentrations of concern.

More recently it has been discovered that VI impacts can occur via sewer and other subsurface piping connections in areas where vapor migration through the soil would not be expected to be significant, and this could also occur in buildings that do not sit over contaminated groundwater[10][7][8][9].

Therefore, in addition to groundwater and soil gas sampling, external data collection that includes and extends beyond the area of concern should include manhole vapor sampling (e.g., sanitary sewer, storm sewer, land-drain). Video surveys from sanitary sewers, storm sewers, and/or land-drains can also be used to identify areas of groundwater leakage into utility corridors and lateral connections to buildings that are conduits for vapor transport. During these investigations, it is important to recognize that utility corridors can transmit both impacted water and vapors beyond groundwater plume boundaries, so extending investigations into areas adjacent to groundwater plume boundaries is necessary.

Using projected indoor air concentrations from modeling and empirical data analyses, and distance screening approaches, external source screening can identify areas and buildings that can be ruled out, or conversely, those that warrant building-specific testing.

Demonstration of neighborhood-scale external VI source screening using groundwater, depth, sewer, land drain, and video data is documented in the ER-201501 final report[1].

Indoor air source screening seeks to locate and remove indoor air sources[11] that might confound building specific VI pathway assessment. Visual inspections and written surveys might or might not identify significant indoor air sources, so these should be complemented with use of portable analytical instruments[12][13].

The advantage of portable analytical tools is that they allow practitioners to expeditiously test indoor air concentrations under natural conditions in each room of the building. Concentrations in any room in excess of relevant screening levels trigger more sampling in that room to identify if an indoor source is present in that room. Removal of a suspected source and subsequent room testing can identify if that object or product was the source of the previously measured concentrations.

Building-specific controlled pressurization method (CPM) testing directly measures the worst case indoor air impact, but it can also be used to determine contributing VI pathways and to identify indoor air sources[14][13][7][15][1][16]. In CPM testing, blowers/fans installed in a doorway(s) or window(s) are set-up to exhaust indoor air to outdoor, which causes the building to be under pressurized relative to the atmosphere. This induces air movement from the subsurface into the test building via openings in the foundation and/or subsurface piping networks with or without direct connections to indoor air. This is similar to what happens intermittently under natural conditions when wind, indoor-outdoor temperature differences, and/or use of appliances that exhaust air from the structure (e.g. dryer exhaust) create an under-pressurized building condition.

The blowers/fans can also be used to blow outdoor air into the building, thereby creating a building over-pressurization condition. A positive pressure difference CPM test suppresses VI pathways; therefore, chemicals detected in indoor air above outdoor air concentrations during this condition are attributed to indoor contaminant sources which facilitates the identification of any such indoor air sources.

Data collected during CPM testing, when combined with screening level VI modeling, can be used to identify which VI chemical migration pathways are significant contributors to indoor air impacts[7].

Nationwide, the liability due to contaminated sediments is estimated in the trillions of dollars. Stakeholders are assessing and developing remedial strategies for contaminated sediment sites in major harbors and waterways throughout the U.S. The mobility of contaminants in surface water is a primary transport and risk mechanism[17][18][19]; therefore, long-term monitoring of both particulate- and dissolved-phase contaminant concentration prior to, during, and following remedial action is necessary to document remedy effectiveness. Source control and total maximum daily load (TMDL) actions generally require costly manual monitoring of dissolved and particulate contaminant concentrations in surface water. The magnitude of cost for these actions is a strong motivation to implement efficient methods for long-term source control and remedial monitoring.

Traditional surface water monitoring requires mobilization of field teams to manually collect discrete water samples, send samples to laboratories, and await laboratory analysis so that a site evaluation can be conducted. These traditional methods are well known to have inherent cost and safety concerns and are of limited use (due to safety concerns and standby requirements for resources) in capturing the effects of episodic events (e.g., storms) that are important to consider in site risk assessment and remedy selection. Automated water samplers are commercially available but still require significant field support and costly laboratory analysis. Further, automated samplers may not be suitable for analytes with short hold-times and temperature requirements.

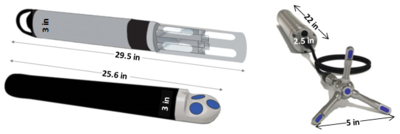

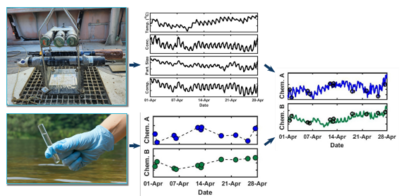

Optically-based characterization of surface water contaminants is a cost-effective alternative to traditional discrete water sampling methods. Unlike discrete water sampling, which typically results in sparse data at low resolution, and therefore, is of limited use in determining mass loading, OPTICS (OPTically-based In-situ Characterization System) provides continuous data and allows for a complete understanding of water quality and contaminant transport in response to natural processes and human impacts[20][21][22][23][24][25]. The OPTICS tool integrates commercial off-the-shelf in situ aquatic sensors (Figure 1), periodic discrete surface water sample collection, and a multi-parameter statistical prediction model[26][27] to provide high temporal and/or spatial resolution characterization of surface water chemicals of potential concern (COPCs) (Figure 2).

Technology Overview

The principle behind OPTICS is based on the relationship between optical properties of natural waters and the particles and dissolved material contained within them[28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35]. Surface water COPCs such as heavy metals and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are hydrophobic in nature and tend to sorb to materials in the water column, which have unique optical signatures that can be measured at high-resolution using in situ, commercially available aquatic sensors[36][37][38][39]. Therefore, high-resolution concentrations of COPCs can be accurately and robustly derived from in situ measurements using statistical methods.

The OPTICS method is analogous to the commonly used empirical derivation of total suspended solids concentration (TSS) from optical turbidity using linear regression[40]. However, rather than deriving one response variable (TSS) from one predictor variable (turbidity), OPTICS involves derivation of one response variable (e.g., PCB concentration) from a suite of predictor variables (e.g., turbidity, temperature, salinity, and fluorescence of chlorophyll-a) using multi-parameter statistical regression. OPTICS is based on statistical correlation – similar to the turbidity-to-TSS regression technique. The method does not rely on interpolation or extrapolation.

The OPTICS technique utilizes partial least-squares (PLS) regression to determine a combination of physical, optical, and water quality properties that best predicts chemical contaminant concentrations with high variance. PLS regression is a statistically based method combining multiple linear regression and principal component analysis (PCA), where multiple linear regression finds a combination of predictors that best fit a response and PCA finds combinations of predictors with large variance[26][27]. Therefore, PLS identifies combinations of multi-collinear predictors (in situ, high-resolution physical, optical, and water quality measurements) that have large covariance with the response values (discrete surface water chemical contaminant concentration data from samples that are collected periodically, coincident with in situ measurements). PLS combines information about the variances of both the predictors and the responses, while also considering the correlations among them. PLS therefore provides a model with reliable predictive power.

OPTICS in situ measurement parameters include, but are not limited to current velocity, conductivity, temperature, depth, turbidity, dissolved oxygen, and fluorescence of chlorophyll-a and dissolved organic matter. Instrumentation for these measurements is commercially available, robust, deployable in a wide variety of configurations (e.g., moored, vessel-mounted, etc.), powered by batteries, and records data internally and/or transmits data in real-time. The physical, optical, and water quality instrumentation is compact and self-contained. The modularity and automated nature of the OPTICS measurement system enables robust, long-term, autonomous data collection for near-continuous monitoring.

OPTICS measurements are provided at a significantly reduced cost relative to traditional monitoring techniques used within the environmental industry. Cost performance analysis shows that monitoring costs are reduced by more than 85% while significantly increasing the temporal and spatial resolution of sampling. The reduced cost of monitoring makes this technology suitable for a number of environmental applications including, but not limited to site baseline characterization, source control evaluation, dredge or stormflow plume characterization, and remedy performance monitoring. OPTICS has been successfully demonstrated for characterizing a wide variety of COPCs: mercury, methylmercury, copper, lead, PCBs, dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) and its related compounds (collectively, DDX), and 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD or dioxin) in a number of different environmental systems ranging from inland lakes and rivers to the coastal ocean. To date, OPTICS has been limited to surface water applications. Additional applications (e.g., groundwater) would require further research and development.

Applications

An OPTICS study was conducted at Berry’s Creek Study Area (BCSA), New Jersey in 2014 and 2015 to understand COPC sources and transport mechanisms for development of an effective remediation plan. OPTICS successfully extended periodic discrete surface water samples to continuous, high-resolution measurements of PCBs, mercury, and methylmercury to elucidate COPC sources and transport throughout the BCSA tidal estuary system. OPTICS provided data at resolution sufficient to investigate COC variability in the context of physical processes. The results (Figure 3) facilitated focused and effective site remediation and management decisions that could not be determined based on periodic discrete samples alone, despite over seven years of monitoring at different locations throughout the system over a range of different seasons, tidal phases, and environmental conditions. The BCSA OPTICS methodology and its results have undergone official peer review overseen by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), and those results have been published in peer-reviewed literature[20].

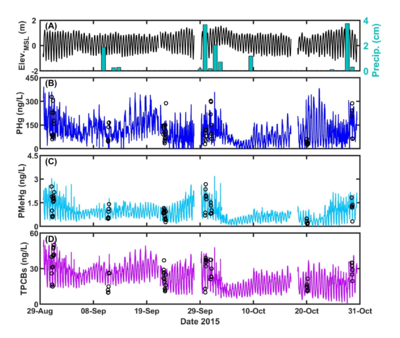

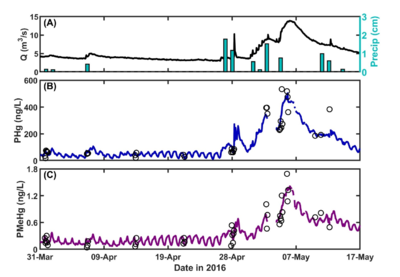

OPTICS was applied at the South River, Virginia in 2016 to quantify sources of legacy mercury in the system that are contributing to recontamination and continued elevated mercury concentrations in fish tissue. OPTICS provided information necessary to identify mechanisms for COPC redistribution and to quantify the relative contribution of each mechanism to total mass transport of mercury and methylmercury in the system. Continuous, high-resolution COPC data afforded by OPTICS helped resolve baseflow daily cycling that had never before been observed at the South River (Figure 4) and provided data at temporal resolution necessary to verify storm-induced particle-bound COC resuspension and mobilization through bank interaction. The results informed source control and remedy design and monitoring efforts. Methodology and results from the South River have been published in peer-reviewed literature[21].

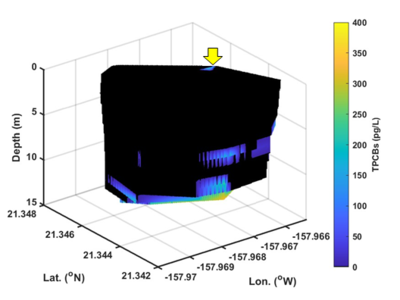

The U.S. Department of Defense’s Environmental Security Technology Certification Program (ESTCP) supported an OPTICS demonstration study at the Pearl Harbor Sediment Site, Hawaii, to determine whether stormwater from Oscar 1 Pier outfall is a contributing source of PCBs to Decision Unit (DU) N-2 (ESTCP Project ER21-5021). High spatial resolution results afforded by ship-based, mobile OPTICS monitoring suggested that PCBs were discharged from the outfall, remained in suspension, and dispersed elsewhere before settling (Figure 5). More details regarding this study were presented by Chang et al. in 2024[22].

Summary

OPTICS provides:

- High resolution surface water chemical contaminant characterization

- Cost-effective monitoring and assessment

- Versatile and modular monitoring with capability for real-time telemetry

- Data necessary for development and validation of conceptual site models

- A key line of evidence for designing and evaluating remedies.

Because OPTICS monitoring involves deployment of autonomous sampling instrumentation, a substantially greater volume of data can be collected using this technique compared to traditional sampling, and at a far lower cost. A large volume of data supports evaluation of chemical contaminant concentrations over a range of spatial and temporal scales, and the system can be customized for a variety of environmental applications. OPTICS helps quantify contaminant mass flux and the relative contribution of local transport and source areas to net contaminant transport. OPTICS delivers a strong line of evidence for evaluating contaminant sources, fate, and transport, and for supporting the design of a remedy tailored to address site-specific, risk-driving conditions. The improved understanding of site processes aids in the development of mitigation measures that minimize site risks.

References

- ^ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Johnson, P.C., Guo, Y., Dahlen, P., 2020. The VI Diagnosis Toolkit for Assessing Vapor Intrusion Pathways and Mitigating Impacts in Neighborhoods Overlying Dissolved Chlorinated Solvent Plumes. ESTCP Project ER-201501, Final Report. Project Website Final Report.pdf

- ^ Johnson, P.C., Guo, Y., Dahlen, P., 2021. CPM Test Guidelines: Use of Controlled Pressure Method Testing for Vapor Intrusion Pathway Assessment. ESTCP ER-201501, Technical Report. Project Website Technical_Report.pdf

- ^ Johnson, P.C., Guo, Y., and Dahlen, P., 2022. VI Diagnosis Toolkit User Guide, ESTCP ER-201501, User Guide. Project Website User_Guide.pdf

- ^ 4.0 4.1 USEPA, 2015. OSWER Technical Guide for Assessing and Mitigating the Vapor Intrusion Pathway from Subsurface Vapor Sources to Indoor Air. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response, OSWER Publication No. 9200.2-154, 267 pages. USEPA Website Report.pdf

- ^ NJDEP, 2021. Vapor Intrusion Technical Guidance, Version 5.0. New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, Trenton, NJ. Website Guidance Document.pdf

- ^ Beckley, L, McHugh, T., 2020. A Conceptual Model for Vapor Intrusion from Groundwater Through Sewer Lines. Science of the Total Environment, 698, Article 134283. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134283 Open Access Article

- ^ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Guo, Y., Holton, C., Luo, H., Dahlen, P., Gorder, K., Dettenmaier, E., Johnson, P.C., 2015. Identification of Alternative Vapor Intrusion Pathways Using Controlled Pressure Testing, Soil Gas Monitoring, and Screening Model Calculations. Environmental Science and Technology, 49(22), pp. 13472–13482. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b03564

- ^ 8.0 8.1 McHugh, T., Beckley, L., Sullivan, T., Lutes, C., Truesdale, R., Uppencamp, R., Cosky, B., Zimmerman, J., Schumacher, B., 2017. Evidence of a Sewer Vapor Transport Pathway at the USEPA Vapor Intrusion Research Duplex. Science of the Total Environment, pp. 598, 772-779. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.04.135 Open Access Manuscipt

- ^ 9.0 9.1 McHugh, T., Beckley, L., 2018. Sewers and Utility Tunnels as Preferential Pathways for Volatile Organic Compound Migration into Buildings: Risk Factors and Investigation Protocol. ESTCP ER-201505, Final Report. Project Website Final Report.pdf

- ^ 10.0 10.1 Riis, C., Hansen, M.H., Nielsen, H.H., Christensen, A.G., Terkelsen, M., 2010. Vapor Intrusion through Sewer Systems: Migration Pathways of Chlorinated Solvents from Groundwater to Indoor Air. Seventh International Conference on Remediation of Chlorinated and Recalcitrant Compounds, May, Monterey, CA. Battelle Memorial Institute. ISBN 978-0-9819730-2-9. Website Report.pdf

- ^ Doucette, W.J., Hall, A.J., Gorder, K.A., 2010. Emissions of 1,2-Dichloroethane from Holiday Decorations as a Source of Indoor Air Contamination. Ground Water Monitoring and Remediation, 30(1), pp. 67-73. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6592.2009.01267.x

- ^ McHugh, T., Kuder, T., Fiorenza, S., Gorder, K., Dettenmaier, E., Philp, P., 2011. Application of CSIA to Distinguish Between Vapor Intrusion and Indoor Sources of VOCs. Environmental Science and Technology, 45(14), pp. 5952-5958. doi: 10.1021/es200988d

- ^ 13.0 13.1 Beckley, L., Gorder, K., Dettenmaier, E., Rivera-Duarte, I., McHugh, T., 2014. On-Site Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry (GC/MS) Analysis to Streamline Vapor Intrusion Investigations. Environmental Forensics, 15(3), pp. 234–243. doi: 10.1080/15275922.2014.930941

- ^ McHugh, T.E., Beckley, L., Bailey, D., Gorder, K., Dettenmaier, E., Rivera-Duarte, I., Brock, S., MacGregor, I.C., 2012. Evaluation of Vapor Intrusion Using Controlled Building Pressure. Environmental Science and Technology, 46(9), pp. 4792–4799. doi: 10.1021/es204483g

- ^ Holton, C., Guo, Y., Luo, H., Dahlen, P., Gorder, K., Dettenmaier, E., Johnson, P.C., 2015. Long-Term Evaluation of the Controlled Pressure Method for Assessment of the Vapor Intrusion Pathway. Environmental Science and Technology, 49(4), pp. 2091–2098. doi: 10.1021/es5052342

- ^ Guo, Y., Dahlen, P., Johnson, P.C., 2020a. Development and Validation of a Controlled Pressure Method Test Protocol for Vapor Intrusion Pathway Assessment. Environmental Science and Technology, 54(12), pp. 7117-7125. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c00811

- ^ Thibodeaux, L.J., 1996. Environmental Chemodynamics: Movement of Chemicals in Air, Water, and Soil, 2nd Edition, Volume 110 of Environmental Science and Technology: A Wiley-Interscience Series of Texts and Monographs. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 624 pages. ISBN: 0-471-61295-2

- ^ United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), 2005. Contaminated Sediment Remediation Guidance for Hazardous Waste Sites. Office of Superfund Remediation and Technology Innovation Report, EPA-540-R-05-012. Report.pdf

- ^ Lick, W., 2008. Sediment and Contaminant Transport in Surface Waters. CRC Press. 416 pages. doi: 10.1201/9781420059885

- ^ 20.0 20.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedChangEtAl2019 - ^ 21.0 21.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedChangEtAl2018 - ^ 22.0 22.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedChangEtAl2024 - ^ Bergamaschi, B.A., Fleck, J.A., Downing, B.D., Boss, E., Pellerin, B., Ganju, N.K., Schoellhamer, D.H., Byington, A.A., Heim, W.A., Stephenson, M., Fujii, R., 2011. Methyl mercury dynamics in a tidal wetland quantified using in situ optical measurements. Limnology and Oceanography, 56(4), pp. 1355-1371. doi: 10.4319/lo.2011.56.4.1355 Open Access Article

- ^ Bergamaschi, B.A., Fleck, J.A., Downing, B.D., Boss, E., Pellerin, B.A., Ganju, N.K., Schoellhamer, D.H., Byington, A.A., Heim, W.A., Stephenson, M., Fujii, R., 2012. Mercury Dynamics in a San Francisco Estuary Tidal Wetland: Assessing Dynamics Using In Situ Measurements. Estuaries and Coasts, 35, pp. 1036-1048. doi: 10.1007/s12237-012-9501-3 Open Access Article

- ^ Bergamaschi, B.A., Krabbenhoft, D.P., Aiken, G.R., Patino, E., Rumbold, D.G., Orem, W.H., 2012. Tidally driven export of dissolved organic carbon, total mercury, and methylmercury from a mangrove-dominated estuary. Environmental Science and Technology, 46(3), pp. 1371-1378. doi: 10.1021/es2029137 Open Access Article

- ^ 26.0 26.1 de Jong, S., 1993. SIMPLS: an alternative approach to partial least squares regression. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems, 18(3), pp. 251-263. doi: 10.1016/0169-7439(93)85002-X

- ^ 27.0 27.1 Rosipal, R. and Krämer, N., 2006. Overview and Recent Advances in Partial Least Squares, In: Subspace, Latent Structure, and Feature Selection: Statistical and Optimization Perspectives Workshop, Revised Selected Papers (Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Volume 3940), Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany. pp. 34-51. doi: 10.1007/11752790_2

- ^ Boss, E. and Pegau, W.S., 2001. Relationship of light scattering at an angle in the backward direction to the backscattering coefficient. Applied Optics, 40(30), pp. 5503-5507. doi: 10.1364/AO.40.005503

- ^ Boss, E., Twardowski, M.S., Herring, S., 2001. Shape of the particulate beam spectrum and its inversion to obtain the shape of the particle size distribution. Applied Optics, 40(27), pp. 4884-4893. doi:10/1364/AO.40.004885

- ^ Babin, M., Morel, A., Fournier-Sicre, V., Fell, F., Stramski, D., 2003. Light scattering properties of marine particles in coastal and open ocean waters as related to the particle mass concentration. Limnology and Oceanography, 48(2), pp. 843-859. doi: 10.4319/lo.2003.48.2.0843 Open Access Article

- ^ Coble, P., Hu, C., Gould, R., Chang, G., Wood, M., 2004. Colored dissolved organic matter in the coastal ocean: An optical tool for coastal zone environmental assessment and management. Oceanography, 17(2), pp. 50-59. doi: 10.5670/oceanog.2004.47 Open Access Article

- ^ Sullivan, J.M., Twardowski, M.S., Donaghay, P.L., Freeman, S.A., 2005. Use of optical scattering to discriminate particle types in coastal waters. Applied Optics, 44(9), pp. 1667–1680. doi: 10.1364/AO.44.001667

- ^ Twardowski, M.S., Boss, E., Macdonald, J.B., Pegau, W.S., Barnard, A.H., Zaneveld, J.R.V., 2001. A model for estimating bulk refractive index from the optical backscattering ratio and the implications for understanding particle composition in case I and case II waters. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 106(C7), pp. 14,129-14,142. doi: 10/1029/2000JC000404 Open Access Article

- ^ Chang, G.C., Barnard, A.H., McLean, S., Egli, P.J., Moore, C., Zaneveld, J.R.V., Dickey, T.D., Hanson, A., 2006. In situ optical variability and relationships in the Santa Barbara Channel: implications for remote sensing. Applied Optics, 45(15), pp. 3593–3604. doi: 10.1364/AO.45.003593

- ^ Slade, W.H. and Boss, E., 2015. Spectral attenuation and backscattering as indicators of average particle size. Applied Optics, 54(24), pp. 7264-7277. doi: 10/1364/AO.54.007264 Open Access Article

- ^ Agrawal, Y.C. and Pottsmith, H.C., 2000. Instruments for particle size and settling velocity observations in sediment transport. Marine Geology, 168(1-4), pp. 89-114. doi: 10.1016/S0025-3227(00)00044-X

- ^ Boss, E., Pegau, W.S., Gardner, W.D., Zaneveld, J.R.V., Barnard, A.H., Twardowski, M.S., Chang, G.C., Dickey, T.D., 2001. Spectral particulate attenuation and particle size distribution in the bottom boundary layer of a continental shelf. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 106(C5), pp. 9509-9516. doi: 10.1029/2000JC900077 Open Access Article

- ^ Boss, E., Pegau, W.S., Lee, M., Twardowski, M., Shybanov, E., Korotaev, G. Baratange, F., 2004. Particulate backscattering ratio at LEO 15 and its use to study particle composition and distribution. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 109(C1), Article C01014. doi: 10.1029/2002JC001514 Open Access Article

- ^ Briggs, N.T., Slade, W.H., Boss, E., Perry, M.J., 2013. Method for estimating mean particle size from high-frequency fluctuations in beam attenuation or scattering measurement. Applied Optics, 52(27), pp. 6710-6725. doi: 10.1364/AO.52.006710 Open Access Article

- ^ Rasmussen, P.P., Gray, J.R., Glysson, G.D., Ziegler, A.C., 2009. Guidelines and procedures for computing time-series suspended-sediment concentrations and loads from in-stream turbidity-sensor and streamflow data. In: Techniques and Methods, Book 3: Applications of Hydraulics, Section C: Sediment and Erosion Techniques, Ch. 4. 52 pages. U.S. Geological Survey. Open Access Article