Difference between revisions of "User:Jhurley/sandbox"

(→Introduction) |

(→Introduction) |

||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

[[File:AbioMCredFig2.png | thumb |400px|Figure 2. General mechanism for the reduction of NACs/MCs.]] | [[File:AbioMCredFig2.png | thumb |400px|Figure 2. General mechanism for the reduction of NACs/MCs.]] | ||

| + | [[File:AbioMCredFig3.png | thumb |400px|Figure 3. Schematic of natural attenuation of MCs-impacted soils through chemical reduction.]] | ||

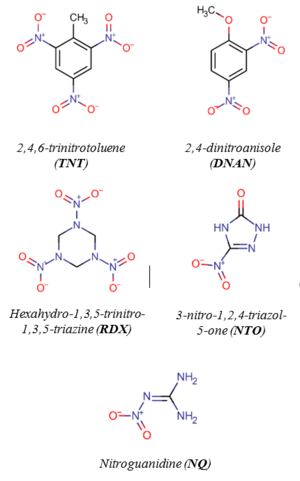

Although the chemical structures of MCs can vary significantly (Figure 1), most of them contain at least one nitro functional group (-NO<sub>2</sub>), which is susceptible to reductive transformation<ref name="Spain2000">Spain, J.C., Hughes, J.B., and Knackmuss, H.J., 2000. Biodegradation of Nitroaromatic Compounds and Explosives. CRC Press, 456 pages. ISBN: 9780367398491</ref>. Of the MCs shown in Figure 1, 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (TNT), 2,4-dinitroanisole (DNAN), and 3-nitro-1,2,4-triazol-5-one (NTO)<ref name="Harris1996">Harris, N.J., and Lammertsma, K., 1996. Tautomerism, Ionization, and Bond Dissociations of 5-Nitro-2,4-dihydro-3H-1,2,4-triazolone. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 118(34), pp. 8048–8055. [https://doi.org/10.1021/ja960834a DOI: 10.1021/ja960834a]</ref> are nitroaromatic compounds (NACs) and hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine (RDX) and nitroguanidine (NQ) are nitramines. The structural differences may result in different reactivities and reaction pathways. Reduction of NACs results in the formation of aromatic amines (i.e., anilines) with nitroso and hydroxylamine compounds as intermediates (Figure 2)<ref name="Schwarzenbach2016"/>. | Although the chemical structures of MCs can vary significantly (Figure 1), most of them contain at least one nitro functional group (-NO<sub>2</sub>), which is susceptible to reductive transformation<ref name="Spain2000">Spain, J.C., Hughes, J.B., and Knackmuss, H.J., 2000. Biodegradation of Nitroaromatic Compounds and Explosives. CRC Press, 456 pages. ISBN: 9780367398491</ref>. Of the MCs shown in Figure 1, 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (TNT), 2,4-dinitroanisole (DNAN), and 3-nitro-1,2,4-triazol-5-one (NTO)<ref name="Harris1996">Harris, N.J., and Lammertsma, K., 1996. Tautomerism, Ionization, and Bond Dissociations of 5-Nitro-2,4-dihydro-3H-1,2,4-triazolone. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 118(34), pp. 8048–8055. [https://doi.org/10.1021/ja960834a DOI: 10.1021/ja960834a]</ref> are nitroaromatic compounds (NACs) and hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine (RDX) and nitroguanidine (NQ) are nitramines. The structural differences may result in different reactivities and reaction pathways. Reduction of NACs results in the formation of aromatic amines (i.e., anilines) with nitroso and hydroxylamine compounds as intermediates (Figure 2)<ref name="Schwarzenbach2016"/>. | ||

Revision as of 10:08, 7 March 2022

Abiotic Reduction of Munitions Constituents

Munition compounds (MCs) often contain one or more nitro (-NO2) functional groups which makes them susceptible to abiotic reduction, i.e., transformation by accepting electrons from a chemical electron donor. In soil and groundwater, the most prevalent electron donors are natural organic carbon and iron minerals. Understanding the kinetics and mechanisms of abiotic reduction of MCs by carbon and iron constituents in soil is not only essential for evaluating the environmental fate of MCs but also key to developing cost-efficient remediation strategies. This article summarizes the recent advances in our understanding of MC reduction by carbon and iron based reductants.

Related Article(s):

Contributor(s):

- Dr. Jimmy Murillo-Gelvez

- Paula Andrea Cárdenas-Hernández

- Dr. Pei Chiu

Key Resource(s):

- Schwarzenbach, Gschwend, and Imboden, 2016. Environmental Organic Chemistry, 3rd ed.[1]

Introduction

Legacy and insensitive MCs (Figure 1.) are susceptible to reductive transformation in soil and groundwater. Many redox-active constituents in the subsurface, especially those containing organic carbon, Fe(II), and sulfur can mediate MC reduction. Specific examples include Fe(II)-organic complexes[2][3][4][5][6], iron oxides in the presence of aqueous Fe(II)[7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17], magnetite[12][14][18][19][20], Fe(II)-bearing clays[21][22][23][24][25][26][27], hydroquinones (as surrogates of natural organic matter)[4][28][29][30][31][32][33], dissolved organic matter[34][35][36], black carbon[37][38][39][40][41][42], and sulfides[43][44]. These geo-reductants may control the fate and half-lives of MCs in the environment and can be used to promote MC degradation in soil and groundwater through enhanced natural attenuation[45].

Although the chemical structures of MCs can vary significantly (Figure 1), most of them contain at least one nitro functional group (-NO2), which is susceptible to reductive transformation[46]. Of the MCs shown in Figure 1, 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (TNT), 2,4-dinitroanisole (DNAN), and 3-nitro-1,2,4-triazol-5-one (NTO)[47] are nitroaromatic compounds (NACs) and hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine (RDX) and nitroguanidine (NQ) are nitramines. The structural differences may result in different reactivities and reaction pathways. Reduction of NACs results in the formation of aromatic amines (i.e., anilines) with nitroso and hydroxylamine compounds as intermediates (Figure 2)[1].

Although the final reduction products are different for non-aromatic MCs, the reduction process often starts with the transformation of the -NO2 moiety, either through de-nitration (e.g., RDX

Application of Plasma for the Treatment of PFAS-Contaminated Water

Several research groups have investigated the use of plasma to treat and remove PFAS from contaminated water[48][49][50][51][52][53][54][55][56]. Of those studies, the Enhanced Contact (EC) plasma reactor developed by researchers at Clarkson University is one of the most promising in terms of treatment time, cost, the range of PFAS treated and scale up/throughput. Their process has been shown to degrade PFOA, PFOS, and other PFAS in a variety of PFAS-impacted water sources.

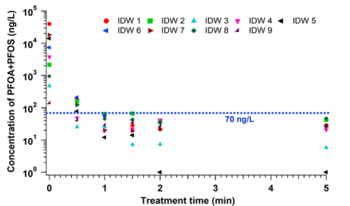

In the EC plasma reactor (Figure 2), argon gas is continuously pumped through the solution to form a layer of foam and thus concentrate PFAS at the gas-liquid interface where plasma is formed. The process is able to lower the concentrations of PFOA and PFOS in groundwater obtained from multiple DoD sites to below Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s) lifetime health advisory level (HAL) of 70 parts per trillion (70 nanogram per liter, ng/L)[58] within 1 minute of treatment (Figure 3) with energy requirements much lower than those of alternative technologies (~2-6 kWh/m3 for plasma vs. 5000 kWh/m3 for persulfate, photochemical oxidation and sonolytic processes and 132 kWh/m3 for electrochemical oxidation)[57][59]. The EC plasma reactor owes its high efficacy to the plasma reactor design, in particular to the gas bubbling through submerged diffusers to transport PFAS to the plasma-liquid interface and thus minimize bulk liquid limitations.

In 2019, a mobile plasma treatment system (Figure 4) was successfully demonstrated for the treatment of PFAS-contaminated groundwater at the fire-training area at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base[60].

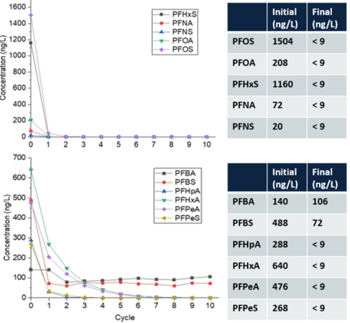

Over 300 gallons of PFAS-impacted groundwater were treated at a maximum flowrate of 1.1 gallons per minute (gpm) resulting in ≥90% reduction (mean percent removal of 99.7%) of long-chain PFAAs (fluorocarbon chain ≥ 6) and PFAS precursors in a single pass through the reactor (Figure 5) at a treatment cost of $7.30/1000 gallons[60]. As expected, the removal of short-chain PFAS was slower due to their lower potential for interfacial adsorption compared to long-chain PFAS. However, post-field laboratory studies revealed that the addition of a cationic surfactant such as CTAB (cetrimonium bromide) minimizes bulk liquid transport limitations for short-chain PFAS by electrostatically interacting with these compounds and transporting them to the plasma-liquid interface where they are degraded[56]. Both bench and pilot-scale EC plasma-based process have been extended for the treatment of PFAS in membrane concentrate, ion exchange brine, and landfill leachate[61][62].

As a part of a currently-funded ESTCP project (ESTCP ER20-5535)[63], the Clarkson University team with the support of GSI Environmental Inc. is evaluating the effectiveness of their plasma process in treating diluted aqueous film-forming foams (AFFFs) as well as the benefits of pre-oxidation of PFAS precursors in high concentration AFFF solutions in terms of post-oxidation plasma treatment time, destruction efficiency and cost.

Advantages and Limitations of the Technology for PFAS Treatment

Advantages:

- High removal rates of long-chain PFAS (C5-C8) due to the production of versatile reactive species

- Requires no chemical additions and produces no residual waste

- Total organic carbon (TOC) concentration and other non-surfactant co-contaminants do not influence the process efficiency

- The process is mobile and scalable

- Versatile: can be used in batch and continuous systems

Limitations:

- Limited removal of short-chain PFAS due to their inability to concentrate at plasma-liquid interfaces. Addition of surfactants such as CTAB improves their removal and degradation rates.

- Excessive foaming caused by bubbling argon gas through a solution containing high (>10 mg/L) concentrations of long-chain (surfactant) PFAS may interfere with the formation of plasma.

Summary

PFAS are susceptible to plasma treatment because the hydrophobic PFAS accumulates at the gas-liquid interface, exposing more of the PFAS to the plasma. Plasma-based treatment of PFAS contaminated water successfully degrades PFOA and PFOS to below the EPA health advisory level of 70 ppt and accomplishes the near complete destruction of other PFAS within a short treatment time. PFAS concentration reductions of ≥90% and post-treatment concentrations below laboratory detection levels are common for long chain PFAS and precursors. The lack of sensitivity of plasma to co-contaminants, coupled with high PFAS removal and defluorination efficiencies, makes plasma-based water treatment a promising technology for the remediation of PFAS-contaminated water. The plasma treatment process is currently developed for ex situ application and can also be integrated into a treatment train[64].

References

- ^ 1.0 1.1 Schwarzenbach, R.P., Gschwend, P.M., and Imboden, D.M., 2016. Environmental Organic Chemistry, 3rd Edition. John Wiley and Sons, Ltd, 1024 pages. ISBN: 978-1-118-76723-8

- ^ Naka, D., Kim, D., and Strathmann, T.J., 2006. Abiotic Reduction of Nitroaromatic Compounds by Aqueous Iron(II)−Catechol Complexes. Environmental Science and Technology 40(9), pp. 3006–3012. DOI: 10.1021/es060044t

- ^ Naka, D., Kim, D., Carbonaro, R.F., and Strathmann, T.J., 2008. Abiotic reduction of nitroaromatic contaminants by iron(II) complexes with organothiol ligands. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 27(6), pp. 1257–1266. DOI: 10.1897/07-505.1

- ^ 4.0 4.1 Hartenbach, A.E., Hofstetter, T.B., Aeschbacher, M., Sander, M., Kim, D., Strathmann, T.J., Arnold, W.A., Cramer, C.J., and Schwarzenbach, R.P., 2008. Variability of Nitrogen Isotope Fractionation during the Reduction of Nitroaromatic Compounds with Dissolved Reductants. Environmental Science and Technology 42(22), pp. 8352–8359. DOI: 10.1021/es801063u

- ^ Kim, D., Duckworth, O.W., and Strathmann, T.J., 2009. Hydroxamate siderophore-promoted reactions between iron(II) and nitroaromatic groundwater contaminants. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 73(5), pp. 1297–1311. DOI: 10.1016/j.gca.2008.11.039

- ^ Kim, D., and Strathmann, T.J., 2007. Role of Organically Complexed Iron(II) Species in the Reductive Transformation of RDX in Anoxic Environments. Environmental Science and Technology, 41(4), pp. 1257–1264. DOI: 10.1021/es062365a

- ^ Colón, D., Weber, E.J., and Anderson, J.L., 2006. QSAR Study of the Reduction of Nitroaromatics by Fe(II) Species. Environmental Science and Technology, 40(16), pp. 4976–4982. DOI: 10.1021/es052425x

- ^ Luan, F., Xie, L., Li, J., and Zhou, Q., 2013. Abiotic reduction of nitroaromatic compounds by Fe(II) associated with iron oxides and humic acid. Chemosphere, 91(7), pp. 1035–1041. DOI: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.01.070

- ^ Gorski, C.A., Edwards, R., Sander, M., Hofstetter, T.B., and Stewart, S.M., 2016. Thermodynamic Characterization of Iron Oxide–Aqueous Fe2+ Redox Couples. Environmental Science and Technology, 50(16), pp. 8538–8547. DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.6b02661

- ^ Fan, D., Bradley, M.J., Hinkle, A.W., Johnson, R.L., and Tratnyek, P.G., 2016. Chemical Reactivity Probes for Assessing Abiotic Natural Attenuation by Reducing Iron Minerals. Environmental Science and Technology, 50(4), pp. 1868–1876. DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.5b05800

- ^ Jones, A.M., Kinsela, A.S., Collins, R.N., and Waite, T.D., 2016. The reduction of 4-chloronitrobenzene by Fe(II)-Fe(III) oxide systems - correlations with reduction potential and inhibition by silicate. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 320, pp. 143–149. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.08.031

- ^ 12.0 12.1 Klausen, J., Troeber, S.P., Haderlein, S.B., and Schwarzenbach, R.P., 1995. Reduction of Substituted Nitrobenzenes by Fe(II) in Aqueous Mineral Suspensions. Environmental Science and Technology, 29(9), pp. 2396–2404. DOI: 10.1021/es00009a036

- ^ Strehlau, J.H., Stemig, M.S., Penn, R.L., and Arnold, W.A., 2016. Facet-Dependent Oxidative Goethite Growth As a Function of Aqueous Solution Conditions. Environmental Science and Technology, 50(19), pp. 10406–10412. DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.6b02436

- ^ 14.0 14.1 Elsner, M., Schwarzenbach, R.P., and Haderlein, S.B., 2004. Reactivity of Fe(II)-Bearing Minerals toward Reductive Transformation of Organic Contaminants. Environmental Science and Technology, 38(3), pp. 799–807. DOI: 10.1021/es0345569

- ^ Colón, D., Weber, E.J., and Anderson, J.L., 2008. Effect of Natural Organic Matter on the Reduction of Nitroaromatics by Fe(II) Species. Environmental Science and Technology, 42(17), pp. 6538–6543. DOI: 10.1021/es8004249

- ^ Stewart, S.M., Hofstetter, T.B., Joshi, P. and Gorski, C.A., 2018. Linking Thermodynamics to Pollutant Reduction Kinetics by Fe2+ Bound to Iron Oxides. Environmental Science and Technology, 52(10), pp. 5600–5609. DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.8b00481 Open access article.

- ^ Klupinski, T.P., Chin, Y.P., and Traina, S.J., 2004. Abiotic Degradation of Pentachloronitrobenzene by Fe(II): Reactions on Goethite and Iron Oxide Nanoparticles. Environmental Science and Technology, 38(16), pp. 4353–4360. DOI: 10.1021/es035434j

- ^ Heijman, C.G., Holliger, C., Glaus, M.A., Schwarzenbach, R.P., and Zeyer, J., 1993. Abiotic Reduction of 4-Chloronitrobenzene to 4-Chloroaniline in a Dissimilatory Iron-Reducing Enrichment Culture. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 59(12), pp. 4350–4353. DOI: 10.1128/aem.59.12.4350-4353.1993 Open access article.

- ^ Gorski, C.A., and Scherer, M.M., 2009. Influence of Magnetite Stoichiometry on FeII Uptake and Nitrobenzene Reduction. Environmental Science and Technology, 43(10), pp. 3675–3680. DOI: 10.1021/es803613a

- ^ Gorski, C.A., Nurmi, J.T., Tratnyek, P.G., Hofstetter, T.B. and Scherer, M.M., 2010. Redox Behavior of Magnetite: Implications for Contaminant Reduction. Environmental Science and Technology, 44(1), pp. 55–60. DOI: 10.1021/es9016848

- ^ Hofstetter, T.B., Neumann, A., and Schwarzenbach, R.P., 2006. Reduction of Nitroaromatic Compounds by Fe(II) Species Associated with Iron-Rich Smectites. Environmental Science and Technology, 40(1), pp. 235–242. DOI: 10.1021/es0515147

- ^ Schultz, C. A., and Grundl, T.J., 2000. pH Dependence on Reduction Rate of 4-Cl-Nitrobenzene by Fe(II)/Montmorillonite Systems. Environmental Science and Technology 34(17), pp. 3641–3648. DOI: 10.1021/es990931e

- ^ Luan, F., Gorski, C.A., and Burgos, W.D., 2015. Linear Free Energy Relationships for the Biotic and Abiotic Reduction of Nitroaromatic Compounds. Environmental Science and Technology, 49(6), pp. 3557–3565. DOI: 10.1021/es5060918

- ^ Luan, F., Liu, Y., Griffin, A.M., Gorski, C.A. and Burgos, W.D., 2015. Iron(III)-Bearing Clay Minerals Enhance Bioreduction of Nitrobenzene by Shewanella putrefaciens CN32. Environmental Science and Technology, 49(3), pp. 1418–1426. DOI: 10.1021/es504149y

- ^ Hofstetter, T.B., Schwarzenbach, R.P. and Haderlein, S.B., 2003. Reactivity of Fe(II) Species Associated with Clay Minerals. Environmental Science and Technology, 37(3), pp. 519–528. DOI: 10.1021/es025955r

- ^ Neumann, A., Hofstetter, T.B., Lüssi, M., Cirpka, O.A., Petit, S., and Schwarzenbach, R.P., 2008. Assessing the Redox Reactivity of Structural Iron in Smectites Using Nitroaromatic Compounds As Kinetic Probes. Environmental Science and Technology, 42(22), pp. 8381–8387. DOI: 10.1021/es801840x

- ^ Hofstetter, T.B., Neumann, A., Arnold, W.A., Hartenbach, A.E., Bolotin, J., Cramer, C.J., and Schwarzenbach, R.P., 2008. Substituent Effects on Nitrogen Isotope Fractionation During Abiotic Reduction of Nitroaromatic Compounds. Environmental Science and Technology, 42(6), pp. 1997–2003. DOI: 10.1021/es702471k

- ^ Schwarzenbach, R.P., Stierli, R., Lanz, K., and Zeyer, J., 1990. Quinone and Iron Porphyrin Mediated Reduction of Nitroaromatic Compounds in Homogeneous Aqueous Solution. Environmental Science and Technology, 24(10), pp. 1566–1574. DOI: 10.1021/es00080a017

- ^ Tratnyek, P.G., and Macalady, D.L., 1989. Abiotic Reduction of Nitro Aromatic Pesticides in Anaerobic Laboratory Systems. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 37(1), pp. 248–254. DOI: 10.1021/jf00085a058

- ^ Hofstetter, T.B., Heijman, C.G., Haderlein, S.B., Holliger, C. and Schwarzenbach, R.P., 1999. Complete Reduction of TNT and Other (Poly)nitroaromatic Compounds under Iron-Reducing Subsurface Conditions. Environmental Science and Technology, 33(9), pp. 1479–1487. DOI: 10.1021/es9809760

- ^ Murillo-Gelvez, J., Hickey, K.P., Di Toro, D.M., Allen, H.E., Carbonaro, R.F., and Chiu, P.C., 2019. Experimental Validation of Hydrogen Atom Transfer Gibbs Free Energy as a Predictor of Nitroaromatic Reduction Rate Constants. Environmental Science and Technology, 53(10), pp. 5816–5827. DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.9b00910

- ^ Niedźwiecka, J.B., Drew, S.R., Schlautman, M.A., Millerick, K.A., Grubbs, E., Tharayil, N. and Finneran, K.T., 2017. Iron and Electron Shuttle Mediated (Bio)degradation of 2,4-Dinitroanisole (DNAN). Environmental Science and Technology, 51(18), pp. 10729–10735. DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.7b02433

- ^ Kwon, M.J., and Finneran, K.T., 2006. Microbially Mediated Biodegradation of Hexahydro-1,3,5-Trinitro-1,3,5- Triazine by Extracellular Electron Shuttling Compounds. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 72(9), pp. 5933–5941. DOI: 10.1128/AEM.00660-06 Open access article.

- ^ Dunnivant, F.M., Schwarzenbach, R.P., and Macalady, D.L., 1992. Reduction of Substituted Nitrobenzenes in Aqueous Solutions Containing Natural Organic Matter. Environmental Science and Technology, 26(11), pp. 2133–2141. DOI: 10.1021/es00035a010

- ^ Luan, F., Burgos, W.D., Xie, L., and Zhou, Q., 2010. Bioreduction of Nitrobenzene, Natural Organic Matter, and Hematite by Shewanella putrefaciens CN32. Environmental Science and Technology, 44(1), pp. 184–190. DOI: 10.1021/es901585z

- ^ Murillo-Gelvez, J., di Toro, D.M., Allen, H.E., Carbonaro, R.F., and Chiu, P.C., 2021. Reductive Transformation of 3-Nitro-1,2,4-triazol-5-one (NTO) by Leonardite Humic Acid and Anthraquinone-2,6-disulfonate (AQDS). Environmental Science and Technology, 55(19), pp. 12973–12983. DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.1c03333

- ^ Oh, S.-Y., Son, J.G., and Chiu, P.C., 2013. Biochar-Mediated Reductive Transformation of Nitro Herbicides and Explosives. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 32(3), pp. 501–508. DOI: 10.1002/etc.2087 Open access article.

- ^ Oh, S.-Y., and Chiu, P.C., 2009. Graphite- and Soot-Mediated Reduction of 2,4-Dinitrotoluene and Hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine. Environmental Science & Technology, 43(18), pp. 6983–6988. DOI: 10.1021/es901433m

- ^ Xu, W., Pignatello, J.J., and Mitch, W.A., 2015. Reduction of Nitroaromatics Sorbed to Black Carbon by Direct Reaction with Sorbed Sulfides. Environmental Science and Technology, 49(6), pp. 3419–3426. DOI: 10.1021/es5045198

- ^ Oh, S.-Y., Cha, D.K., and Chiu, P.C., 2002. Graphite-Mediated Reduction of 2,4-Dinitrotoluene with Elemental Iron. Environmental Science and Technology, 36(10), pp. 2178–2184. DOI: 10.1021/es011474g

- ^ Amezquita-Garcia, H.J., Razo-Flores, E., Cervantes, F.J., and Rangel-Mendez, J.R., 2013. Activated carbon fibers as redox mediators for the increased reduction of nitroaromatics. Carbon, 55, pp. 276–284. DOI: 10.1016/j.carbon.2012.12.062

- ^ Xin, D., Girón, J., Fuller, M.E., and Chiu, P.C., 2022. Abiotic Reduction of 3-Nitro-1,2,4-triazol-5-one (NTO) and Other Munitions Constituents by Wood-Derived Biochar through Its Rechargeable Electron Storage Capacity. Environmental Science: Processes and Impacts, 24(2), pp. 316-329. DOI: 10.1039/D1EM00447F

- ^ Hojo, M., Takagi, Y. and Ogata, Y., 1960. Kinetics of the Reduction of Nitrobenzenes by Sodium Disulfide. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 82(10), pp. 2459–2462. DOI: 10.1021/ja01495a017

- ^ Zeng, T., Chin, Y.P., and Arnold, W.A., 2012. Potential for Abiotic Reduction of Pesticides in Prairie Pothole Porewaters. Environmental Science and Technology, 46(6), pp. 3177–3187. DOI: 10.1021/es203584d

- ^ US EPA, 2012. A Citizen’s Guide to Monitored Natural Attenuation. EPA document 542-F-12-014. Free download.

- ^ Spain, J.C., Hughes, J.B., and Knackmuss, H.J., 2000. Biodegradation of Nitroaromatic Compounds and Explosives. CRC Press, 456 pages. ISBN: 9780367398491

- ^ Harris, N.J., and Lammertsma, K., 1996. Tautomerism, Ionization, and Bond Dissociations of 5-Nitro-2,4-dihydro-3H-1,2,4-triazolone. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 118(34), pp. 8048–8055. DOI: 10.1021/ja960834a

- ^ Hayashi, R., Obo, H., Takeuchi, N., and Yasuoka, K., 2015. Decomposition of Perfluorinated Compounds in Water by DC Plasma within Oxygen Bubbles. Electrical Engineering in Japan, 190(3), pp.9-16. DOI: 10.1002/eej.22499 Open access article.

- ^ Matsuya, Y., Takeuchi, N., Yasuoka, K., 2014. Relationship Between Reaction Rate of Perfluorocarboxylic Acid Decomposition at a Plasma-Liquid Interface and Adsorbed Amount. Electrical Engineering in Japan, 188(2), pp.1-8. DOI: 10.1002/eej.22526 Open access article.

- ^ Stratton, G.R., Dai, F., Bellona, C.L., Holsen, T.M., Dickenson, E.R., and Mededovic Thagard, S., 2017. Plasma-Based Water Treatment: Efficient Transformation of Perfluoroalkyl Substances in Prepared Solutions and Contaminated Groundwater. Environmental Science and Technology, 51(3), pp.1643-1648. DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.6b04215

- ^ Takeuchi, N., Kitagawa, Y., Kosugi, A., Tachibana, K., Obo, H., and Yasuoka, K., 2013. Plasma-Liquid Interfacial Reaction in Decomposition of Perfluoro Surfactants. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics, 47(4), p.045203. DOI: 10.1088/0022-3727/47/4/045203

- ^ Yasuoka, K., Sasaki, K., and Hayashi, R., 2011. An Energy-Efficient Process for Decomposing Perfluorooctanoic and Perfluorooctane Sulfonic Acids Using DC Plasmas Generated within Gas Bubbles. Plasma Sources Science and Technology, 20(3), p. 034009. DOI: 10.1088/0963-0252/20/3/034009

- ^ Yasuoka, K., Sasaki, K., Hayashi, R., Kosugi, A., and Takeuchi, N., 2010. Degradation of Perfluoro Compounds and F- Recovery in Water Using Discharge Plasmas Generated within Gas Bubbles. International Journal of Plasma Environmental Science and Technology, 4(2), 113–117. Open access article.

- ^ Lewis, A.J., Joyce, T., Hadaya, M., Ebrahimi, F., Dragiev, I., Giardetti, N., Yang, J., Fridman, G., Rabinovich, A., Fridman, A.A., McKenzie, E.R., and Sales, C.M., 2020. Rapid Degradation of PFAS in Aqueous Solutions by Reverse Vortex Flow Gliding Arc Plasma. Environmental Science: Water Research and Technology, 6(4), pp.1044-1057. DOI: 10.1039/c9ew01050e

- ^ Saleem, M., Biondo, O., Sretenović, G., Tomei, G., Magarotto, M., Pavarin, D., Marotta, E. and Paradisi, C., 2020. Comparative Performance Assessment of Plasma Reactors for the Treatment of PFOA; Reactor Design, Kinetics, Mineralization and Energy Yield. Chemical Engineering Journal, 382, p.123031. DOI: 10.1016/j.cej.2019.123031

- ^ 56.0 56.1 Palma, D., Papagiannaki, D., Lai, M., Binetti, R., Sleiman, M., Minella, M. and Richard, C., 2021. PFAS Degradation in Ultrapure and Groundwater Using Non-Thermal Plasma. Molecules, 26(4), p. 924. DOI: 10.3390/molecules26040924 Open access article.

- ^ 57.0 57.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedSingh2019a - ^ US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), 2016. Lifetime Health Advisories and Health Effects Support Documents for Perfluorooctanoic Acid and Perfluorooctane Sulfonate. Federal Register, Notices, 81(101), p. 33250-33251. Free download.

- ^ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedNzeribe2019 - ^ 60.0 60.1 60.2 Nau-Hix, C., Multari, N., Singh, R.K., Richardson, S., Kulkarni, P., Anderson, R.H., Holsen, T.M. and Mededovic Thagard, S., 2021. Field Demonstration of a Pilot-Scale Plasma Reactor for the Rapid Removal of Poly-and Perfluoroalkyl Substances in Groundwater. ACS ES&T Water, 1(3), pp. 680-687. DOI: 10.1021/acsestwater.0c00170

- ^ Singh, R.K., Multari, N., Nau-Hix, C., Woodard, S., Nickelsen, M., Mededovic Thagard, S. and Holsen, T.M., 2020. Removal of Poly- And Per-Fluorinated Compounds from Ion Exchange Regenerant Still Bottom Samples in a Plasma Reactor. Environmental Science and Technology, 54(21), pp.13973-13980. DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.0c02158

- ^ Singh, R.K., Brown, E., Mededovic Thagard, S., and Holsen, T.M., 2021. Treatment of PFAS-Containing Landfill Leachate Using an Enhanced Contact Plasma Reactor. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 408, p.124452. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124452

- ^ Mededovic, S., 2020. An Innovative Plasma Technology for Treatment of AFFF Rinsate from Firefighting Delivery Systems. Environmental Security Technology Certification Program (ESTCP), Project ER20-5355. Project Overview

- ^ Richardson, S., 2021. Nanofiltration Followed by Electrical Discharge Plasma for Destruction of PFAS and Co-occurring Chemicals in Groundwater: A Treatment Train Approach. Environmental Security Technology Certification Program (ESTCP), Project Number ER21-5136. Project Overview