Difference between revisions of "User:Jhurley/sandbox"

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

==Introduction== | ==Introduction== | ||

| + | [[File: Plasma4PFASFig1.png | thumb |700px|Figure 1. Plasmas generated within liquids (Courtesy of Plasma Research Laboratory, Clarkson University)]] | ||

Plasma processing plays an essential role in various industrial applications such as semiconductor fabrication, polymer functionalization, chemical synthesis, agriculture and food safety, health industry, and hazardous waste management<ref name="VanVeldhuizen2002">Van Veldhuizen, E.M., and Rutgers, W.R., 2002. Pulsed Positive Corona Streamer Propagation and Branching. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics, 35(17), p.2169. [https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/35/17/313 DOI: 10.1088/0022-3727/35/17/313]</ref><ref name="Yang">Yang, Y., Cho, Y.I. and Fridman, A., 2012. Plasma Discharge in Liquid: Water Treatment and Applications. CRC press. ISBN: 978-1-4398-6623-8 [https://doi.org/10.1201/b11650 DOI: 10.1201/b11650]</ref><ref name="Rezaei2019">Rezaei, F., Vanraes, P., Nikiforov, A., Morent, R., and De Geyter, N., 2019. Applications of Plasma-Liquid Systems: A Review. Materials, 12(17), article 2751, 69 pp. [https://doi.org/10.3390/ma12172751 DOI: 10.3390/ma12172751] [https://www.mdpi.com/1996-1944/12/17/2751 Open access article].</ref><ref name="Herianto2021">Herianto, S., Hou, C.Y., Lin, C.M., and Chen, H.L., 2021. Nonthermal plasma-activated water: A comprehensive review of this new tool for enhanced food safety and quality. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 20(1), pp. 583-626. [https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4337.12667 DOI: 10.1111/1541-4337.12667]</ref>. Plasma is a gaseous state of matter consisting of charged particles, metastable-state molecules or atoms, and free radicals. Depending on the energy or temperature of the electrons, compared with the temperature of the background gas, plasmas can be classified as thermal or non-thermal. In thermal plasma, an example of which is an electrical arc, individual species’ temperatures typically exceed several thousand kelvins (K). Non-thermal plasmas are formed using less power with temperatures ranging from ambient to approximately 1000 K<ref name="Jiang2014">Jiang, B., Zheng, J., Qiu, S., Wu, M., Zhang, Q., Yan, Z. and Xue, Q., 2014. Review on Electrical Discharge Plasma Technology for Wastewater Remediation. Chemical Engineering Journal, 236, pp. 348–368. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2013.09.090 DOI: 10.1016/j.cej.2013.09.090]</ref>. An example of a non-thermal plasma is a dielectric barrier discharge used for commercial ozone generation. | Plasma processing plays an essential role in various industrial applications such as semiconductor fabrication, polymer functionalization, chemical synthesis, agriculture and food safety, health industry, and hazardous waste management<ref name="VanVeldhuizen2002">Van Veldhuizen, E.M., and Rutgers, W.R., 2002. Pulsed Positive Corona Streamer Propagation and Branching. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics, 35(17), p.2169. [https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/35/17/313 DOI: 10.1088/0022-3727/35/17/313]</ref><ref name="Yang">Yang, Y., Cho, Y.I. and Fridman, A., 2012. Plasma Discharge in Liquid: Water Treatment and Applications. CRC press. ISBN: 978-1-4398-6623-8 [https://doi.org/10.1201/b11650 DOI: 10.1201/b11650]</ref><ref name="Rezaei2019">Rezaei, F., Vanraes, P., Nikiforov, A., Morent, R., and De Geyter, N., 2019. Applications of Plasma-Liquid Systems: A Review. Materials, 12(17), article 2751, 69 pp. [https://doi.org/10.3390/ma12172751 DOI: 10.3390/ma12172751] [https://www.mdpi.com/1996-1944/12/17/2751 Open access article].</ref><ref name="Herianto2021">Herianto, S., Hou, C.Y., Lin, C.M., and Chen, H.L., 2021. Nonthermal plasma-activated water: A comprehensive review of this new tool for enhanced food safety and quality. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 20(1), pp. 583-626. [https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4337.12667 DOI: 10.1111/1541-4337.12667]</ref>. Plasma is a gaseous state of matter consisting of charged particles, metastable-state molecules or atoms, and free radicals. Depending on the energy or temperature of the electrons, compared with the temperature of the background gas, plasmas can be classified as thermal or non-thermal. In thermal plasma, an example of which is an electrical arc, individual species’ temperatures typically exceed several thousand kelvins (K). Non-thermal plasmas are formed using less power with temperatures ranging from ambient to approximately 1000 K<ref name="Jiang2014">Jiang, B., Zheng, J., Qiu, S., Wu, M., Zhang, Q., Yan, Z. and Xue, Q., 2014. Review on Electrical Discharge Plasma Technology for Wastewater Remediation. Chemical Engineering Journal, 236, pp. 348–368. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2013.09.090 DOI: 10.1016/j.cej.2013.09.090]</ref>. An example of a non-thermal plasma is a dielectric barrier discharge used for commercial ozone generation. | ||

Revision as of 11:59, 1 February 2022

PFAS Treatment by Electrical Discharge Plasma

Plasma-based water treatment is a technology that, using only electricity, converts water into a mixture of highly reactive species including OH•, O, H•, HO2•, O2•‒, H2, O2, H2O2 and aqueous electrons (e‒aq), called a plasma[1][2]. These highly reactive species rapidly and non-selectively degrade volatile organic compounds (VOCs)[3], 1,4-dioxane[4][5], and a broad spectrum of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) including perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS), and short-chain PFAS[6][7][8]. A plasma reactor can simultaneously oxidize and reduce organics by producing a mixture of hydroxyl radicals and aqueous electrons, the latter of which act as strong reducing agents and could be the key species in removing PFAS and other non-oxidizable compounds. Additionally, the plasma process produces no residual waste and requires no chemical additions, although adding surfactants or injecting inert gas into the liquid phase can increase interfacial PFAS concentrations, exposing more of the PFAS to the plasma and therefore increasing removal efficiency.

Related Article(s):

Contributor(s):

- Dr. Selma Mededovic Thagard

- Dr. Thomas Holsen

- Dr. Stephen Richardson, P.E

- Poonam Kulkarni, P.E.

- Dr. Blossom Nzeribe

Key Resource(s):

- PFAS – Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances: 12.2 Field-Implemented Liquids Treatment Technologies. Interstate Technology Regulatory Council (ITRC). See also: 12.5 Limited Application and Developing Liquids Treatment Technologies.

- Physico-Chemical Processes for the Treatment of Per- And Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS): A review28[9]

- Low Temperature Plasma for Biology, Hygiene, and Medicine: Perspective and Roadmap[10]

Introduction

Plasma processing plays an essential role in various industrial applications such as semiconductor fabrication, polymer functionalization, chemical synthesis, agriculture and food safety, health industry, and hazardous waste management[11][12][13][14]. Plasma is a gaseous state of matter consisting of charged particles, metastable-state molecules or atoms, and free radicals. Depending on the energy or temperature of the electrons, compared with the temperature of the background gas, plasmas can be classified as thermal or non-thermal. In thermal plasma, an example of which is an electrical arc, individual species’ temperatures typically exceed several thousand kelvins (K). Non-thermal plasmas are formed using less power with temperatures ranging from ambient to approximately 1000 K[15]. An example of a non-thermal plasma is a dielectric barrier discharge used for commercial ozone generation.

Plasma that is applied in water treatment (Figure 1) is typically non-thermal, which offers high-energy process efficiency and selectivity[15][16]. Since the 1980s when the first plasma reactor was utilized to oxidize a dye[17], over a hundred different plasma reactors have been developed to treat a range of contaminants of environmental importance including biological species. Examples include treatment of pharmaceuticals, volatile organic compounds (VOCs), 1,4-dioxane, herbicides, pesticides, warfare agents, bacteria, yeasts and viruses using direct-in-liquid discharges with and without bubbles and discharges in a gas over and contacting the surface of a liquid. Different excitation sources including AC, nanosecond pulsed and DC voltages have been utilized to produce pulsed corona, corona-like, spark, arc, and glow discharges, among other discharge types. Many reviews of plasma processing for water treatment applications have recently been published[18][19].

Plasma-based water treatment (PWT) owes its strong oxidation and disinfection capabilities to the production of reactive oxidative species (ROS), primarily OH radicals, atomic oxygen, singlet oxygen and hydrogen peroxide. The process also produces reductive species such as solvated electrons and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) when nitrogen and oxygen are present in the discharge. This process has the advantage of synergistic effects of high electric fields, UV/VUV light emissions and in some cases shockwave formation in a liquid. It requires no chemical additions, and can be optimized for batch or continuous processing.

Fundamentals of Sediment Risk Assessment

Whereas there is strong evidence of anthropogenic impacts on the benthic community at many sediment sites, the degree of toxicity (or even its presence or absence) cannot be predicted with absolute certainty using contaminant concentrations alone[20]. A sediment ERA should include lines of evidence (LOEs) derived from several different investigations[21]. One common approach to develop several of these LOEs in a decision framework is the triad approach. Triad-based assessment frameworks require evidence based on sediment chemistry, toxicity, and benthic community structure (possibly including evidence of bioaccumulation) to designate sediment as toxic and requiring management or control[22]. In some decision frameworks, particularly those used to establish and rank risks in national or regional programs, all components of the triad are carried out simultaneously, with the various LOEs combined to support weight of evidence (WOE) decision making. In other frameworks, LOEs are tiered to minimize costs by collecting only the data required to make a decision and leaving some potential consequences and uncertainties unresolved.

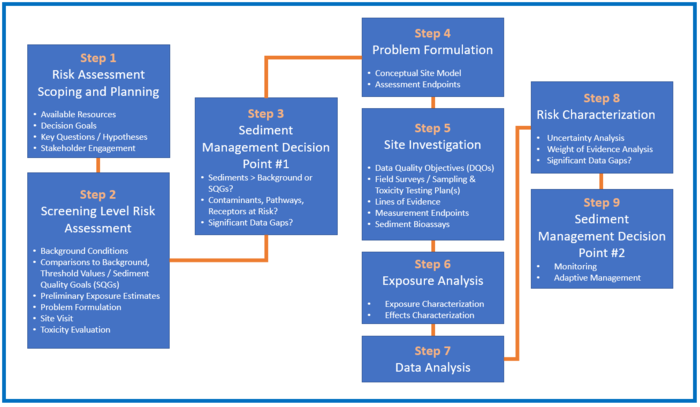

Figure 1 provides an overview of a sediment risk assessment process. The first step, and a fundamental requirement, in sediment risk assessment, involves scoping and planning prior to undertaking work. This is important for optimizing the available assessment resource and conducting an assessment at the appropriate level of detail that is transparent and free, to the extent possible, of any bias or preconceived beliefs concerning the outcome[23].

Screening-Level Risk Assessment (SLRA)

Technical guidance in many countries strongly encourages sediment risk assessment to begin with a Screening-Level Risk Assessment (SLRA)[24][25][26]. The SLRA is a simplified risk assessment conducted using limited data and often assuming certain, generally conservative and generic, sediment characteristics, sediment contaminant levels, and exposure parameters in the absence of sufficient readily available information[27][28][29][30].

The analysis is often semi-quantitative, and typically includes comparisons of various chemical and physical sediment conditions to threshold limits established in national or international regulations or by generally accepted scientific interpretations. US technical guidance encourages the comparison of contaminant measurements in water, sediment, or soil to National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) sediment screening quick reference tables, or SQuiRT cards, which list quality guidelines from a range of sources, based on differing narrative intent[31].

The screening level approach is intended to minimize the chances of concluding that there is no risk when, in fact, risk may exist. Thus, the results of an SLRA may indicate contaminants or sediments in certain locations in the original study area initially thought to be of concern are acceptable (i.e., contaminant levels are below threshold levels), or that contaminant levels are high enough to indicate immediate action without further assessment (e.g., contaminant levels are well above probable-effects guidelines). In other cases, or at other locations, SLRA may indicate the need for further examination. Further study may apply site-specific, rather than generic and conservative assumptions, to reduce uncertainty.

Detailed Risk Assessment

Detailed sediment risk assessment is conducted when SLRA results indicate one or more sediment contaminants exceed background conditions or regulatory threshold limits. For some contaminants, such as the dioxins and other persistent, bioaccumulative, and toxic substances (PBTs), technical guidance may mandate further examination, regardless of whether threshold levels are exceeded[32][33]. Detailed sediment risk assessment typically follows a three-step framework similar to that described for ecological risk assessment - problem formulation, exposure analysis, and risk characterization[34].

US sediment management guidance describes a detailed risk assessment process similar to that followed for US ecological risk assessment[24]. The first step is problem formulation. It involves defining chemical and physical conditions, delineating the spatial footprint of the sediment area to be examined, and identifying the human uses and ecological features of the sediment. Historical data are included in this initial step to better understand the results of biota, sediment, and water sampling as well as laboratory toxicity testing results. The SLRA is often included as a part of problem formulation.

The second step is exposure analysis. This step includes the identification of pathways by which human and aquatic organisms might directly or indirectly contact contaminants in the sediment. The exposure route (i.e., ingestion, dermal, or inhalation of particulates or gaseous emissions) and both the frequency and duration of contact (i.e., hourly, daily, or seasonally) are determined for each contaminant exposure pathway and human and ecological receptor. The environmental fate of the contaminant, factors affecting uptake, and the overall exposure dose are included in the calculation of the level of contaminant exposure. The exposure analysis also includes an effects assessment, whereby the biological response and associated level required to manifest different biological responses are determined for each contaminant.

The third step is risk-characterization. It involves calculating the risks for each human and ecological receptor posed by each sediment contaminant, as well as the cumulative risk associated with the combined exposure to all contaminants exerting similar biological effects. An uncertainty analysis is often included in this step of the risk assessment to convey where knowledge or data are lacking regarding the presence of the contaminant in the sediment, the biological response associated with exposure to the contaminant, or the behavior of the receptor with respect to contact with the sediment. A sensitivity analysis also may be conducted to convey the range of exposures (lowest, typical, and worst-case) and risks associated with changes in key assumptions and parameter values used in the exposure calculations and effects assessment.

Key Considerations

Stakeholder Engagement

Stakeholder involvement is widely acknowledged as an important element of dredged material management[35], sediment remediation[36], and other environmental and sediment related activities[37][38].

Sediment management, particularly at the river basin scale, involves a wide variety of different environmental, governmental, and societal issues[39]. Incorporating these different views, interests, and perspectives into a form that builds consensus for whatever actions and goals are in mind (e.g., commercial ports and shipping, navigation, flood protection, or habitat restoration) necessitates a formal stakeholder engagement process[40].

Results from a three-year (2008-2010) Sediment and Society research project funded by the Norwegian Research Council point to three important challenges that must be resolved for successful stakeholder engagement: (1) how to include people who have important management information and local knowledge, but not much influence in the decision-making process; (2) how to secure resources to ensure participation and (3) how to engage and motivate stakeholders to participate early in the sediment remediation planning process[36].

Conceptual Site Model

The preparation of a conceptual site model (CSM) is a fundamental component of problem formulation and the first step in detailed sediment risk assessment. The CSM is a narrative and/or illustrative representation of the physical, chemical and biological processes that control the transport, migration and actual or potential impacts of sediment contamination to human and/or ecological receptors[41][42]. The CSM should include a “food web” because the aquatic food web is an important exposure pathway by which contaminants in the sediment reach humans and pelagic aquatic life[43].

The CSM provides an early opportunity for critical examination of the interactions between sediment and the water column and the influence of groundwater inputs, surface runoff, and hydrodynamics. For example, there are situations where impacts in the aquatic food web can be driven by ongoing inputs to the water column from upstream sources, but mistakenly connected to polluted sediments. Other considerations included in a CSM can be socio-economic and include linkages to the ecosystem services provided by sediments[44][45], or the social, economic and environmental impacts of sediment management alternatives. In such a case, when risk assessment seeks to compare risks of various management actions (including no action), the CSM can be termed a sustainability CSM, or SustCSM[46][47]. At a minimum, however, the purpose of the CSM is to illustrate the scope of the risk assessment and guide the quantification of exposure and risk.

Environmental Fate

An important consideration in exposure analysis is the determination of the bioavailable fraction of the contaminant in the sediment. There are two considerations. First, the adverse condition may be buried deep enough in sediments to be below the biologically available zone; typically, conditions in sediment below a depth of 5 cm will not contact burrowing benthic organisms[48]. If there is no prospect for the adverse condition to come closer to the surface, then the risk assessment could conclude the risk of exposure is insignificant. The second consideration relates to chemistry and the factors involved in the binding to sediment particles or the chemical form of the substance in the sediment[49]. However, these assumptions should be examined in the context of climate change, and the likelihood of more frequent and extreme events, putting burial at risk, higher temperatures and changing biogeochemical conditions, which may alter environmental fate of contaminants, compared to historical studies.

The above contaminant bioavailability considerations are important factors influencing assumptions in the risk assessment about contaminant exposure[50][51]. There have been recent advances in the use of sorbent amendments applied to contaminated sediments that alter sediment geochemistry, increase contaminant binding, and reduce contaminant exposure risks to people and the environment[52]. Passive sampling techniques have emerged to quantify chemical binding to sediment and determine the freely dissolved concentration that is bioavailable.

Assessment and Measurement Endpoints

Assessment and measurement endpoints used in sediment risk assessment are comparable to those described in USEPA ecological risk assessment guidance[24][53][54][55][56]. A sediment risk assessment, and ecological risk assessments more broadly, must have clearly defined endpoints that are socially and biologically relevant, accessible to prediction and measurement, and susceptible to the hazard being assessed[53].

Assessment endpoints for humans include both carcinogenic and noncarcinogenic effects. Due to their assumed higher levels of exposure, human receptors used in sediment risk assessment typically include recreational, commercial, and subsistence fishermen, i.e., people who might be at increased risk from eating fish or contacting the sediment or water on a regular basis such as indigenous peoples, immigrants from fishing cultures, and subsistence fishers who rely upon fish as a major source of protein. Special considerations are given to women of child-bearing age, pregnant women and young children. Assessment endpoints for ecological receptors focus on benthic organisms, resident fish, piscivorous and other predatory birds and marine mammals. Endpoints typically include mortality, reproductive success and population susceptibility to disease or similar adverse chronic conditions.

Measurement endpoints are related quantitatively to each assessment endpoint. Whenever practical, multiple measurement endpoints are chosen to provide additional lines of evidence for each assessment endpoint. For example, for humans, it might be possible to measure contaminant levels in both food items and human blood or tissue. For predatory fish, birds and mammals, it might be possible to measure contaminants in both prey and predator tissues. Measurement endpoints can be selected to assess non-chemical stressors as well, such as habitat alteration and water turbidity. Typically, measurement endpoints are compared to measurements at a reference site to ascertain the degree of departure from local natural or background conditions.

Sediment Toxicity Testing

Sediment bioassays are an integral part of effects characterization when assessing the risks posed by contaminated sediments and developing sediment quality guidelines[57][58]. The selection of appropriate sediment bioassays is dependent on the questions being addressed, the physical and chemical characteristics of the sediment matrix, the nature of the contaminant(s) of concern, and preferences of the supervising regulatory authority for the test method and test organisms[59]. Bioassay procedures have been standardized in several countries, and it is not unusual for different test methods to be required in different countries for the same sediment management purpose[60]. Guidance documents in Australia, Canada, Europe and the US cover the wide range of sediment bioassay procedures most often used in risk assessment[61][62][63][64][65].

In general, sediment toxicity tests focus on either (acute) lethality in whole organisms (typically benthic infaunal species such as amphipods and polychaetes) following short-term or acute exposures (<14 days) or (chronic) sublethal responses (e.g., reduced growth or reproduction or both) following longer-term exposures[58]. It is not unusual in sediment risk assessment to rely on more than one sediment bioassay. Both acute and chronic tests involving either solid-phase or pore-water sediment fractions can be useful to discern the contributions of different contaminants in whole sediment by examining the response of different endpoints in different test organisms[62][63]. The application of more specialized techniques such as toxicity identification evaluations (TIEs) have also proved useful to help identify contaminants or contaminant classes most likely responsible for toxicity and to exclude potentially confounding factors such as ammonia[66][67].

Uncertainty

As part of the overall analysis of risk from exposure to certain sediment conditions, it is generally understood there is a moderate degree of uncertainty associated with sampling and the environmental fate of contaminants; an order of magnitude of uncertainty associated with ecological exposure and dose-response; and greater than an order of magnitude of uncertainty associated with the quantification of potential human health effects[68]. The sources of uncertainty and significance to sediment risk assessment can vary widely, thereby affecting confidence in the decisions made based on risk assessment[69][70].

Consequently, technical guidance in several countries encourages including a quantitative uncertainty analysis in sediment risk assessment[24][25][71][72]. The aim of uncertainty analysis is to express either quantitatively or qualitatively the limitations inherent in predicting exposures and effects and, ultimately, the level of overall risk posed by sediment conditions[73]. Sediment risk assessment increasingly relies on a weight-of-evidence process to improve the certainty of conclusions about whether or not impairment exists due to sediment contamination, and, if so, which stressors and biological species (or ecological responses) are of greatest concern[74]. Recent advancements, including the use of Bayesian networks and geographic information systems, also help capture the range of variability in both measured and predicted exposures and responses[75][76][77]. The level of sophistication applied to the uncertainty analysis is a subjective consideration and often decided by regulatory pressures, public perceptions and the likely cost (not only economic, but also social and environmental) of mitigating or removing the contamination.

Role in Sediment Management

Whether or not remediation of contaminated sediments is warranted depends on the magnitude of direct or indirect health risks to humans, ecological threats to aquatic biota, and the extent of risk reduction that can be achieved by removal or containment of the contamination[78]. As all sediment management also introduces risk pathways, such as sediment re-suspension leading to contaminant release, possible impacts due to land, water and energy usage, and risk to workers, remedial decision-making should also consider the risks posed by the remedial process. There are two types of remediation risks inherent in sediment remediation - engineering and biological. Sediment remedy implementation risks are predominantly short-term engineering issues associated with applying the remedy such as worker and community health and safety, equipment failures, and accident rates[79]. Sediment residual risks are predominantly longer-term changes in exposure and effects to humans, aquatic biota, and wildlife after the remedy has been implemented[79].

In addition to evaluating sediment conditions prior to remediation, sediment risk assessment can be useful to understand how the engineering risks, the contaminant exposure pathways, and which human and wildlife populations are at risk might change with different remediation options[80]. Decision tools such as multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA), or sustainability assessment[81][82], for example, incorporate elements from sediment risk assessment to support remediation decision making[83]. Sediment risk assessment also plays an important role in the implementation of monitored natural recovery (MNR) as a remediation strategy[84]. Insofar as ecological recovery is affected by surface‐sediment‐contaminant concentrations, the primary recovery processes for MNR are natural sediment burial and transformation of the contaminant to less toxic forms by biological or chemical processes[85].

Since risk reduction is the long‐term goal of contaminated sediment management[86], predicting the rate at which contaminant exposures and risks are mitigated by sedimentation and degradation over time can be aided by including parameters in the risk assessment that calculate the rate of contaminant removal or decay in the sediment. Evaluating sediment management options in terms of risk reduction involves assessing risks under the diverse set of conditions that include the current state of the site as well as the conditions that would occur both during the implementation work and long after the work is complete and the ecosystem stabilizes[87][88].

Summary

Effective sediment risk assessment begins with an initial scoping and planning exercise. The work proceeds to a SLRA and, if warranted, detailed risk assessment using a process comparable to ecological risk assessment. The key elements of sediment risk assessment must include a well‐designed and site‐specific CSM; a transparent and well‐thought‐out biological and chemical data collection and analysis plan; carefully selected reference sites and decision criteria; and an explicit discussion of uncertainty. If the risk assessment concludes that unacceptable risks exist, risk‐management strategies must be evaluated, selected, implemented, and their success evaluated.

Sediment risk assessments are designed to simulate and predict plausible interactions between contaminants or other stressors and both ecological and human receptors. The intent is to derive meaningful insights that provide conclusions that are both rational and protective, in that they err on the side of over-estimating the likely environmental risks. Although conservative assumptions should always be used early in the sediment risk assessment process, final decisions should be supported by refined, realistic estimates of risk provided by site‐specific data and sound analytical approaches. It is increasingly evident after nearly 50 years of application that sediment risk assessment is most useful when supported by a well‐designed, site‐specific, and tiered assessment process[89].

References

- ^ Sunka, P., Babický, V., Clupek, M., Lukes, P., Simek, M., Schmidt, J., and Cernak, M., 1999. Generation of Chemically Active Species by Electrical Discharges in Water. Plasma Sources Science and Technology, 8(2), pp. 258-265. DOI: 10.1088/0963-0252/8/2/006

- ^ Mededovic Thagard, S., Takashima, K., and Mizuno, A., 2009. Chemistry of the Positive and Negative Electrical Discharges Formed in Liquid Water and Above a Gas-Liquid Surface. Plasma Chemistry and Plasma Processing, 29(6), pp.455-473. DOI: 10.1007/s11090-009-9195-x

- ^ Du, C., Gong, X., and Lin, Y., 2019. Decomposition of volatile organic compounds using corona discharge plasma technology. Journal of the Air and Waste Management Association, 69(8), pp.879-899. DOI: 10.1080/10962247.2019.1582441 Open access article.

- ^ Xiong, Y., Zhang, Q., Wandell, R., Bresch, S., Wang, H., Locke, B.R. and Tang, Y., 2019. Synergistic 1,4-Dioxane Removal by Non-Thermal Plasma Followed by Biodegradation. Chemical Engineering Journal, 361, pp.519-527. DOI: 10.1016/J.CEJ.2018.12.094

- ^ Ni, G.H., Zhao, Y., Meng, Y.D., Wang, X.K., and Toyoda, H., 2013. Steam plasma jet for treatment of contaminated water with high-concentration 1,4-dioxane organic pollutants. Europhysics Letters, 101(4), p.45001. DOI: 10.1209/0295-5075/101/45001

- ^ Stratton, G.R., Bellona, C.L., Dai, F., Holsen, T.M. and Mededovic Thagard, S., 2015. Plasma-Based Water Treatment: Conception and Application of a New General Principle for Reactor Design. Chemical Engineering Journal, 273, pp.543-550. DOI: 10.1016/j.cej.2015.03.059

- ^ Singh, R.K., Multari, N., Nau-Hix, C., Anderson, R.H., Richardson, S.D., Holsen, T.M. and Mededovic Thagard, S., 2019. Rapid Removal of Poly- and Perfluorinated Compounds from Investigation-Derived Waste (IDW) in a Pilot-Scale Plasma Reactor. Environmental Science and Technology, 53(19), pp.11375-11382. DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.9b02964

- ^ Singh, R.K., Fernando, S., Baygi, S.F., Multari, N., Mededovic Thagard, S., and Holsen, T.M., 2019. Breakdown Products from Perfluorinated Alkyl Substances (PFAS) Degradation in a Plasma-Based Water Treatment Process. Environmental Science and Technology, 53(5), pp.2731-2738. DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.8b07031

- ^ Nzeribe, B.N., Crimi, M., Mededovic Thagard, S. and Holsen, T.M., 2019. Physico-Chemical Processes for the Treatment of Per- And Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS): A review. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology, 49(10), pp.866-915. DOI: 10.1080/10643389.2018.1542916

- ^ Laroussi, M., Bekeschus, S., Keidar, M., Bogaerts, A., Fridman, A., Lu, X.P., Ostrikov, K.K., Hori, M., Stapelmann, K., Miller, V., Reuter, S., Laux, C., Mesbah, A., Walsh, J., Jiang, C., Mededovic Thagard, S., Tanaka, H., Liu, D.W., Yan, D., and Yusupov, M., 2021. Low Temperature Plasma for Biology, Hygiene, and Medicine: Perspective and Roadmap. IEEE Transactions on Radiation and Plasma Medical Sciences. DOI: 10.1109/TRPMS.2021.3135118 Open access article.

- ^ Van Veldhuizen, E.M., and Rutgers, W.R., 2002. Pulsed Positive Corona Streamer Propagation and Branching. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics, 35(17), p.2169. DOI: 10.1088/0022-3727/35/17/313

- ^ Yang, Y., Cho, Y.I. and Fridman, A., 2012. Plasma Discharge in Liquid: Water Treatment and Applications. CRC press. ISBN: 978-1-4398-6623-8 DOI: 10.1201/b11650

- ^ Rezaei, F., Vanraes, P., Nikiforov, A., Morent, R., and De Geyter, N., 2019. Applications of Plasma-Liquid Systems: A Review. Materials, 12(17), article 2751, 69 pp. DOI: 10.3390/ma12172751 Open access article.

- ^ Herianto, S., Hou, C.Y., Lin, C.M., and Chen, H.L., 2021. Nonthermal plasma-activated water: A comprehensive review of this new tool for enhanced food safety and quality. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 20(1), pp. 583-626. DOI: 10.1111/1541-4337.12667

- ^ 15.0 15.1 Jiang, B., Zheng, J., Qiu, S., Wu, M., Zhang, Q., Yan, Z. and Xue, Q., 2014. Review on Electrical Discharge Plasma Technology for Wastewater Remediation. Chemical Engineering Journal, 236, pp. 348–368. DOI: 10.1016/j.cej.2013.09.090

- ^ Magureanu, M., Bradu, C., and Parvulescu, V.I., 2018. Plasma Processes for the Treatment of Water Contaminated with Harmful Organic Compounds. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics, 51(31), p. 313002. DOI: 10.1088/1361-6463/aacd9c

- ^ Clements, J.S., Sato, M., and Davis, R.H., 1987. Preliminary Investigation of Prebreakdown Phenomena and Chemical Reactions Using a Pulsed High-Voltage Discharge in Water. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications, IA-23(2), pp. 224-235. DOI: 10.1109/TIA.1987.4504897

- ^ Zeghioud, H., Nguyen-Tri, P., Khezami, L., Amrane, A., and Assadi, A.A., 2020. Review on Discharge Plasma for Water Treatment: Mechanism, Reactor Geometries, Active Species and Combined Processes. Journal of Water Process Engineering, 38, p.101664. DOI: 10.1016/j.jwpe.2020.101664

- ^ Murugesan, P., Evanjalin Monica, V., Moses, J.A., and Anandharamakrishnan, C., 2020. Water Decontamination Using Non-Thermal Plasma: Concepts, Applications, and Prospects. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 8(5), p. 104377. DOI: 10.1016/j.jece.2020.104377

- ^ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedApitz2011 - ^ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedWenning2005 - ^ Chapman, P.M., Paine, M.D., Arthur, A.D., Taylor, L.A., 1996. A triad study of sediment quality associated with a major, relatively untreated marine sewage discharge. Marine Pollution Bulletin 32(1), pp. 47–64. DOI: 10.1016/0025-326X(95)00108-Y

- ^ Hill, R.A., Chapman, P.M., Mann, G.S. and Lawrence, G.S., 2000. Level of Detail in Ecological Risk Assessments. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 40(6), pp. 471-477. DOI: 10.1016/S0025-326X(00)00036-9

- ^ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedUSEPA2005 - ^ 25.0 25.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedTarazona2014 - ^ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedFletcher2008 - ^ Hope, B.K., 2006. An examination of ecological risk assessment and management practices. Environment International, 32(8), pp. 983-995. DOI: 10.1016/j.envint.2006.06.005

- ^ Weinstein, J.E., Crawford, K.D., Garner, T.R. and Flemming, A.J., 2010. Screening-level ecological and human health risk assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in stormwater detention pond sediments of Coastal South Carolina, USA. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 178(1-3), pp. 906-916. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.02.024

- ^ Rak, A., Maly, M.E., Tracey, G., 2008. A Guide to Screening Level Ecological Risk Assessment, TG-090801. Tri-Services Ecological Risk Assessment Working Group (TSERAWG), U.S. Army Biological Technical Assistance Group (BTAG), Aberdeen Proving Ground, MD. 26 pp. Free Download Report.pdf

- ^ US Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), 2001. ECO Update. The Role of Screening-Level Risk Assessments and Refining Contaminants of Concern in Baseline Ecological Risk Assessments. EPA 540/F-01/014. Washington, D.C. Website Report.pdf

- ^ Buchman, M.F., 2008. Screening Quick Reference Tables (SQuiRTs), NOAA OR&R Report 08-1. National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Coastal Protection and Restoration Protection Division. 34 pp. website Report.pdf

- ^ Solomon, K., Matthies, M., and Vighi, M., 2013. Assessment of PBTs in the European Union: a critical assessment of the proposed evaluation scheme with reference to plant protection products. Environmental Sciences Europe, 25(1), pp. 1-17. DOI: 10.1186/2190-4715-25-10 Open Access Article

- ^ Matthies, M., Solomon, K., Vighi, M., Gilman, A. and Tarazona, J.V., 2016. The origin and evolution of assessment criteria for persistent, bioaccumulative and toxic (PBT) chemicals and persistent organic pollutants (POPs). Environmental Science: Processes and Impacts, 18(9), pp. 1114-1128. DOI: 10.1039/C6EM00311G

- ^ Suter, G.W., 2008. Ecological Risk Assessment in the United States Environmental Protection Agency: A Historical Overview. Integrated Environmental Assessment And Management, 4(3), pp. 285-289. DOI: 10.1897/IEAM_2007-062.1 Free download from: BioOne

- ^ Collier, Z.A., Bates, M.E., Wood, M.D. and Linkov, I., 2014. Stakeholder engagement in dredged material management decisions. Science of the Total Environment, 496, pp. 248-256. DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.07.044 Free download from: ResearchGate

- ^ 36.0 36.1 Oen, A.M.P., Sparrevik, M., Barton, D.N., Nagothu, U.S., Ellen, G.J., Breedveld, G.D., Skei, J. and Slob, A., 2010. Sediment and society: an approach for assessing management of contaminated sediments and stakeholder involvement in Norway. Journal of Soils and Sediments, 10(2), pp. 202-208. DOI: 10.1007/s11368-009-0182-x

- ^ Gerrits, L. and Edelenbos, J., 2004. Management of Sediments Through Stakeholder Involvement. Journal of Soils and Sediments, 4(4), pp. 239-246. DOI: 10.1007/BF02991120

- ^ Braun, A.B., da Silva Trentin, A.W., Visentin, C. and Thomé, A., 2019. Sustainable remediation through the risk management perspective and stakeholder involvement: A systematic and bibliometric view of the literature. Environmental Pollution, 255(1), p.113221. DOI: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113221

- ^ Liu, C., Walling, D.E. and He, Y., 2018. The International Sediment Initiative case studies of sediment problems in river basins and their management. International Journal of Sediment Research, 33(2), pp. 216-219. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijsrc.2017.05.005 Free download from: ResearchGate

- ^ Slob, A.F.L., Ellen, G.J. and Gerrits, L., 2008. Sediment management and stakeholder involvement. In: Sustainable Management of Sediment Resources, Vol. 4: Sediment Management at the River Basin Scale, Owens, P.N. (ed.), pp. 199-216. Elsevier. DOI: 10.1016/S1872-1990(08)80009-8

- ^ New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, 2019. Technical Guidance for Preparation and Submission of a Conceptual Site Model. Version 1.1. Site Remediation and Waste Management Program, Trenton, NJ. 46 pp. Free download.

- ^ US Environmental Protection Agency, 2011. Guidance for the Development of Conceptual Models for a Problem Formulation Developed for Registration Review. Environmental Fate and Effects Division, Office of Pesticide Programs, Washington, D.C. Website

- ^ Arnot, J.A. and Gobas, F.A., 2004. A Food Web Bioaccumulation Model for Organic Chemicals in Aquatic Ecosystems. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 23(10), pp. 2343-2355. DOI: 10.1897/03-438

- ^ Broszeit, S., Beaumont, N.J., Hooper, T.L., Somerfield, P.J. and Austen, M.C., 2019. Developing conceptual models that link multiple ecosystem services to ecological research to aid management and policy, the UK marine example. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 141, pp.236-243. DOI: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.02.051 Open Access Article.

- ^ Wang, J., Lautz, L.S., Nolte, T.M., Posthuma, L., Koopman, K.R., Leuven, R.S. and Hendriks, A.J., 2021. Towards a systematic method for assessing the impact of chemical pollution on ecosystem services of water systems. Journal of Environmental Management, 281, p. 111873. DOI: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111873 Open Access Article.

- ^ McNally, A.D., Fitzpatrick, A.G., Harrison, D., Busey, A., and Apitz, S.E., 2020. Tiered approach to sustainability analysis in sediment remediation decision making. Remediation Journal, 31(1), pp. 29-44. DOI: 10.1002/rem.21661 Open Access Article.

- ^ Holland, K.S., Lewis, R.E., Tipton, K., Karnis, S., Dona, C., Petrovskis, E., and Hook, C., 2011. Framework for Integrating Sustainability Into Remediation Projects. Remediation Journal, 21(3), pp. 7-38. DOI: 10.1002/rem.20288.

- ^ Anderson, R.H., Prues, A.G. and Kravitz, M.J., 2010. Determination of the biologically relevant sampling depth for terrestrial ecological risk assessments. Geoderma, 154(3-4), pp.336-339. DOI: 10.1016/j.geoderma.2009.11.004

- ^ Eggleton, J. and Thomas, K.V., 2004. A review of factors affecting the release and bioavailability of contaminants during sediment disturbance events. Environment International, 30(7), pp. 973-980. DOI: 10.1016/j.envint.2004.03.001

- ^ Peijnenburg, W.J., 2020. Implementation of bioavailability in prospective and retrospective risk assessment of chemicals in soils and sediments. In: The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry, vol 100, Bioavailability of Organic Chemicals in Soil and Sediment, Ortega-Calvo, J.J., Parsons, J.R. (ed.s), pp.391-422. Springer. DOI: 10.1007/698_2020_516

- ^ Ortega-Calvo, J.J., Harmsen, J., Parsons, J.R., Semple, K.T., Aitken, M.D., Ajao, C., Eadsforth, C., Galay-Burgos, M., Naidu, R., Oliver, R. and Peijnenburg, W.J., 2015. From Bioavailability Science to Regulation of Organic Chemicals. Environmental Science and Technology, 49, 10255−10264. DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.5b02412 Open Access Article.

- ^ Ghosh, U., Luthy, R.G., Cornelissen, G., Werner, D. and Menzie, C.A., 2011. In-situ sorbent amendments: a new direction in contaminated sediment management. Environmental Science and Technology, 45, 4, 1163–1168. DOI: 10.1021/es102694h Open Access Article

- ^ 53.0 53.1 US Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), 1992. Framework for Ecological Risk Assessment, EPA/630/R-92/001. Risk Assessment Forum, Washington DC. Report.pdf

- ^ US Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), 1996. Eco Update: Ecological Significance and Selection of Candidate Assessment Endpoints. EPA/540/F-95/037. Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response, Washington DC. Report.pdf

- ^ US Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), 1997. Ecological Risk Assessment Guidance for Superfund: Process for Designing and Conducting Ecological Risk Assessments - Interim Final, EPA 540/R-97/006. Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response, Washington DC. Report.pdf

- ^ US Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), 1998. Guidelines for Ecological Risk Assessment. EPA/630/R-95/002F. Risk Assessment Forum, Washington DC. Report.pdf

- ^ US Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), 2014. Toxicity Testing and Ecological Risk Assessment Guidance for Benthic Invertebrates. Office of Chemical Safety and Pollution Prevention, Washington DC. Website Report.pdf

- ^ 58.0 58.1 Simpson, S., Campana, O., Ho, K., 2016. Chapter 7, Sediment Toxicity Testing. In: J. Blasco, P.M. Chapman, O. Campana, M. Hampel (ed.s), Marine Ecotoxicology: Current Knowledge and Future Issues. Academic Press Incorporated. pp. 199-237. DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-12-803371-5.00007-2

- ^ Amiard-Triquet, C., Amiard, J.C. and Mouneyrac, C. (ed.s), 2015. Aquatic Ecotoxicology: Advancing Tools For Dealing With Emerging Risks. Academic Press, NY. ISBN #9780128009499. DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800949-9.12001-7

- ^ DelValls, T.A., Andres, A., Belzunce, M.J., Buceta, J.L., Casado-Martinez, M.C., Castro, R., Riba, I., Viguri, J.R. and Blasco, J., 2004. Chemical and ecotoxicological guidelines for managing disposal of dredged material. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 23(10-11), pp. 819-828. DOI: 10.1016/j.trac.2004.07.014 Free download from: Academia.edu

- ^ Bat, L., 2005. A Review of Sediment Toxicity Bioassays Using the Amphipods and Polychaetes. Turkish Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 5(2), pp. 119-139. Free download Report.pdf

- ^ 62.0 62.1 Keddy, C.J., Greene, J.C. and Bonnell, M.A., 1995. Review of Whole-Organism Bioassays: Soil, Freshwater Sediment, and Freshwater Assessment in Canada. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 30(3), pp. 221-251. DOI: 10.1006/eesa.1995.1027

- ^ 63.0 63.1 Giesy, J.P., Rosiu, C.J., Graney, R.L. and Henry, M.G., 1990. Benthic invertebrate bioassays with toxic sediment and pore water. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 9(2), pp. 233-248. DOI: 10.1002/etc.5620090214

- ^ Simpson, S. and Batley, G. (ed.s), 2016. Sediment Quality Assessment: A Practical Guide, Second Edition. 358 pp. CSIRO Publishing, Australia. ISBN # 9781486303847.

- ^ Moore, D.W., Farrar, D., Altman, S. and Bridges, T.S., 2019. Comparison of Acute and Chronic Toxicity Laboratory Bioassay Endpoints with Benthic Community Responses in Field‐Exposed Contaminated Sediments. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 38(8), pp. 1784-1802. DOI: 10.1002/etc.4454

- ^ Ho, K.T. and Burgess, R.M., 2013. What's causing toxicity in sediments? Results of 20 years of toxicity identification and evaluations. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 32(11), pp. 2424-2432. DOI: 10.1002/etc.2359

- ^ Bailey, H.C., Curran, C.A., Arth, P., Lo, B.P. and Gossett, R., 2016. Application of sediment toxicity identification evaluation techniques to a site with multiple contaminants. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 35(10), pp. 2456-2465. DOI: 10.1002/etc.3488

- ^ Di Guardo, A., Gouin, T., MacLeod, M. and Scheringer, M., 2018. Environmental fate and exposure models: advances and challenges in 21st century chemical risk assessment. Environmental Science: Processes and Impacts, 20(1), pp. 58-71. DOI: 10.1039/C7EM00568G Open access article

- ^ Reckhow, K.H., 1994. Water quality simulation modeling and uncertainty analysis for risk assessment and decision making. Ecological Modelling, 72(1-2), pp.1-20. DOI: 10.1016/0304-3800(94)90143-0

- ^ Chapman, P.M., Ho, K.T., Munns Jr, W.R., Solomon, K. and Weinstein, M.P., 2002. Issues in sediment toxicity and ecological risk assessment. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 44(4), pp. 271-278. DOI: 10.1016/S0025-326X(01)00329-0

- ^ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedApitz2005a - ^ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedApitz2005b - ^ Batley, G.E., Burton, G.A., Chapman, P.M. and Forbes, V.E., 2002. Uncertainties in Sediment Quality Weight-of-Evidence (WOE) Assessments. Human and Ecological Risk Assessment, 8(7), pp. 1517-1547. DOI: 10.1080/20028091057466

- ^ Burton, G.A., Batley, G.E., Chapman, P.M., Forbes, V.E., Smith, E.P., Reynoldson, T., Schlekat, C.E., Besten, P.J.D., Bailer, A.J., Green, A.S. and Dwyer, R.L., 2002. A Weight-of-Evidence Framework for Assessing Sediment (or Other) Contamination: Improving Certainty in the Decision-Making Process. Human and Ecological Risk Assessment, 8(7), pp. 1675-1696. DOI: 10.1080/20028091056854

- ^ Holsman, K., Samhouri, J., Cook, G., Hazen, E., Olsen, E., Dillard, M., Kasperski, S., Gaichas, S., Kelble, C.R., Fogarty, M. and Andrews, K., 2017. An ecosystem‐based approach to marine risk assessment. Ecosystem Health and Sustainability, 3(1), p. e01256. DOI: 10.1002/ehs2.1256 Open access article

- ^ Marcot, B.G. and Penman, T.D., 2019. Advances in Bayesian network modelling: Integration of modelling technologies. Environmental Modelling and Software, 111, pp. 386-393. DOI: 10.1016/j.envsoft.2018.09.016

- ^ Men, C., Liu, R., Wang, Q., Guo, L., Miao, Y. and Shen, Z., 2019. Uncertainty analysis in source apportionment of heavy metals in road dust based on positive matrix factorization model and geographic information system. Science of The Total Environment, 652, pp. 27-39. DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.10.212

- ^ Kvasnicka, J., Burton Jr, G.A., Semrau, J. and Jolliet, O., 2020. Dredging Contaminated Sediments: Is it Worth the Risks? Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 39(3), pp. 515-516. DOI: 10.1002/etc.4679 Open access article

- ^ 79.0 79.1 Wenning, R.J., Sorensen, M. and Magar, V.S., 2006. Importance of Implementation and Residual Risk Analyses in Sediment Remediation. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management, 2(1), pp. 59-65. DOI: 10.1002/ieam.5630020111 Open access article

- ^ National Research Council (NRC), 2001. A Risk‐Management Strategy For PCB Contaminated Sediments. Committee On Remediation Of PCB‐Contaminated Sediments, Board On Environmental Studies And Toxicology. National Academies Press, Washington DC. 452 pp. ISBN: 0-309-58873-1 DOI: 10.17226/10041 Free download from: The National Academies Press

- ^ Apitz, S.E., Fitzpatrick, A., McNally, A., Harrison, D., Coughlin, C., and Edwards, D.A., 2018. Stakeholder Value-Linked Sustainability Assessment: Evaluating Remedial Alternatives for the Portland Harbor Superfund Site, Portland, Oregon, USA. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management, 14(1), pp. 43-62. DOI: 10.1002/ieam.1998 Open access article

- ^ Fitzpatrick, A., Apitz, S.E., Harrison, D., Ruffle, B., and Edwards, D.A., 2018. The Portland Harbor Superfund Site Sustainability Project: Introduction. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management, 14(1), pp. 17-21. DOI: 10.1002/ieam.197 Open access article

- ^ Linkov, I., Satterstrom, F.K., Kiker, G., Seager, T.P., Bridges, T., Gardner, K.H., Rogers, S.H., Belluck, D.A. and Meyer, A., 2006. Multicriteria Decision Analysis: A Comprehensive Decision Approach for Management of Contaminated Sediments. Risk Analysis, 26(1), pp. 61-78. DOI: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2006.00713.x Free download from: US Army Corps of Engineers

- ^ Magar, V.S. and Wenning, R.J., 2006. The role of monitored natural recovery in sediment remediation. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management, 2(1), pp. 66-74. DOI: 10.1002/ieam.5630020112 Open access article

- ^ Magar, V.S., Chadwick, D.B., Bridges, T.S., Fuchsman, P.C., Conder, J.M., Dekker, T.J., Steevens, J.A., Gustavson, K.E. and Mills, M.A., 2009. Technical Guide: Monitored Natural Recovery at Contaminated Sediment Sites. Environmental Security Technology Certification Program (ESTCP) Project ER-0622. 277 pp. Website Free download

- ^ Apitz, S.E. and Power, E.A., 2002. From Risk Assessment to Sediment Management: An International Perspective. Journal of Soils and Sediments, 2(2), pp. 61-66. DOI: 10.1007/BF02987872 Free download from: ResearchGate

- ^ Linkov, I., Satterstrom, F.K., Kiker, G.A., Bridges, T.S., Benjamin, S.L. and Belluck, D.A., 2006. From Optimization to Adaptation: Shifting Paradigms in Environmental Management and Their Application to Remedial Decisions. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management, 2(1), pp. 92-98. DOI: 10.1002/ieam.5630020116 Open access article

- ^ Reible, D., Hayes, D., Lue-Hing, C., Patterson, J., Bhowmik, N., Johnson, M. and Teal, J., 2003. Comparison of the Long-Term Risks of Removal and In Situ Management of Contaminated Sediments in the Fox River. Soil and Sediment Contamination, 12(3), pp. 325-344. DOI: 10.1080/713610975

- ^ Bridges, T., Berry, W., Della Sala, S., Dorn, P., Ells, S., Gries, T., Ireland, S., Maher, E., Menzie, C., Porebski, L., and Stronkhorst, J., 2005. Chapter 6: A framework for assessing and managing risks from contaminated sediments. In: Use of sediment quality guidelines and related tools for the assessment of contaminated sediments. Wenning, Batley, Ingersoll, and Moore, editors. Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry (SETAC), pp. 227–266. ISBN: 1-880611-71-6