Difference between revisions of "User:Admin/sandbox"

| (269 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | Climate change affects both terrestrial<ref>Diffenbaugh, N. S. and Field, C. B., 2013. Changes in Ecologically Critical Terrestrial Climate Conditions. Science, 341(6145), pp. 486-492. [https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1237123 doi: 10.1126/science.1237123]</ref> and aquatic biomes<ref>Hoegh-Guldberg, O., and Bruno, J. F., 2010. The Impact of Climate Change on the World’s Marine Ecosystem. Science, 328(5985), pp. 1523-1528. [https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1189930 doi: 10.1126/science.1189930]</ref> causing significant effects on ecosystem functions and biodiversity<ref name=":0">Bellard, C., Berteslsmeier, C., Leadley, P., Thuiller, W., and Courchamp, F., 2012. Impacts of climate change on the future of biodiversity. Ecological Letters, 15(4), pp. 365-377. [https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01736.x doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01736.x] [//www.enviro.wiki/images/a/a4/Bellard2012.pdf Article pdf]</ref>. Climate change is affecting several key ecological processes and patterns that will have cascading impacts on wildlife and habitat<ref name=":1">Inkley, D. B., Anderson, M. G., Blaustein, A. R., Burkett, V. R., Felzer, B., Griffith, B., Price, J., and Root, T. L., 2004. Global Climate Change and Wildlife in North America. Wildlife Society Technical Review 04-2. The Wildlife Society, Bethesda, MD, 26 pp. [//www.enviro.wiki/images/f/f1/Inkley2004.pdf Report pdf]</ref>. For example, sea-level rise, changes in the timing and duration of growing seasons, and changes in primary production are mainly driven by changes to global environmental variables (e.g., temperature and atmospheric CO<sub>2</sub>). Climate-induced changes in the environment ultimately impact wildlife population abundance and distributions. | |

| − | + | <br /> | |

| − | |||

<div style="float:right;margin:0 0 2em 2em;">__TOC__</div> | <div style="float:right;margin:0 0 2em 2em;">__TOC__</div> | ||

'''Related Article(s):''' | '''Related Article(s):''' | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | *[[Climate Change Primer|Climate Change]] | ||

| + | *[[Predicting Species Responses to Climate Change with Population Models]] | ||

| − | |||

| + | '''Contributor(s):''' Dr. Breanna F. Powers and Dr. Julie A. Heath | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | '''Key Resource(s):''' | |

| − | ''' | ||

| − | + | *Global climate change and wildlife in North America. Wildlife Society Technical Review 04-2<ref name=":1" /> | |

| + | *Impacts of climate change on the future of biodiversity<ref name=":0" /> | ||

| − | + | ==Introduction== | |

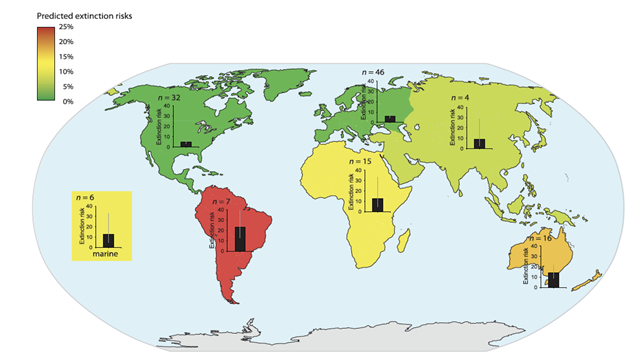

| + | [[File:PowersFig1.png|thumb|900px|left | Figure 1. The predicted extinction risk (by percentage with 95% CIs) from climate change by different regions, colors represent a gradient from least to most extinction risks (green to red) based upon the number of relevant studies (n). Figure is from Urban (2015)<ref name=":2" />. Reprinted with permission from AAAS. Any use of this figure requires the prior written permission of AAAS]] | ||

| + | Global climate change will affect ecosystem functions and cycles such as nutrient, hydraulic, and carbon cycles, changing aspects of environmental conditions such as temperature, soil moisture, and precipitation<ref>Davidson, E. A. and Janssens, I. A., 2006. Temperature sensitivity of soil carbon decomposition and feedbacks to climate change. Nature, 440, pp. 165-173.[https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04514 doi: 10.1038/nature04514]</ref><ref>Melillo, J. M., McGuire, A. D., Kicklighter, D. W., Moore, B., Vorosmarty, C. J., and Schloss, A. L., 1993. Global climate change and terrestrial net primary production. Nature, 363, pp. 234-240. [https://doi.org/10.1038/363234a0 doi: 10.1038/363234a0]</ref>. Wildlife species are adapted to their environments and changes to the environment and habitat conditions will mediate effects, either directly or indirectly, on species survival, fecundity and ultimately population persistence<ref>Alig, R. J., Technical Coordinator, 2011. Effects of Climate Change on Natural Resources and Communities: A Compendium of Briefing Papers. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, General Technical Report, [https://www.fs.usda.gov/treesearch/pubs/37513 PNW-GTR-837], Portland, OR, 169p. [https://doi.org/10.2737/PNW-GTR-837 doi:10.2737/PNW-GTR-837] [//www.enviro.wiki/images/f/f2/Pnwgtr837.pdf Report pdf]</ref><ref>Acevedo-Whitehouse, K., and Duffus, A. L. J., 2009. Effects of environmental change on wildlife health. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 364(1534), pp. 3429-3438. [https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2009.0128 doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0128]</ref><ref>Milligan, S. R., Holt, W. V., and Lloyd, R., 2009. Impacts of climate change and environmental factors on reproduction and development in wildlife. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 364(1534), pp. 3313-3319. [https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2009.0175 doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0175] [//www.enviro.wiki/images/a/ad/Milligan2009.pdf Article pdf]</ref>. The ability to adapt to changing habitat conditions as a result of climate change will differ across individual species and between populations. Some wildlife species may be more vulnerable to climate change than other species (Figure 1). Vulnerability is often linked to particular life-history traits (e.g., specialized habitat needs or limited dispersal abilities, see Pacifici et al. 2015P<ref>Pacifici, M., Foden, W., and Visconti, P., 2015. Assessing species vulnerability to climate change. Nature Climate Change 5, pp. 215-225. [https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2448 doi: 10.1038/nclimate2448]</ref> for a review on species vulnerability to climate change) or genetic composition. For example, grassland birds may be more vulnerable to changing climate than forest birds as forests can buffer change more so than grasslands<ref>Jarzyna, M. A., Zuckerberg, B., Finley, A. O., and Porter, W. F., 2016. Synergistic effects of climate change and land cover: grassland birds are more vulnerable to climate change. Landscape Ecology, 31(10), pp. 2275-2290. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-016-0399-1 doi: 10.1007/s10980-016-0399-1]</ref>. Projected changes in the climate will generally have adverse effects of wildlife populations<ref>IPCC, 2001. Climate Change 2001: Synthesis Report. A Contribution of Working Groups I, II, and III to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. R.T. Watson and the Core Writing Team (eds.). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom, and New York, NY, USA, 398p. [//www.enviro.wiki/images/5/56/IPCC2001.pdf Report pdf]</ref>, though there are some species coping with climate change or benefitting from environmental change. For example, American kestrels (Falco sparverius) have shifted their breeding phenology to earlier in the year and may now raise two broods of young within a breeding season<ref>Smith, S. H., Steenhof, K., McClure, C. J. W., and Heath, J. A. 2017. Earlier nesting by generalist predatory bird is associated with human responses to climate change. Journal of Animal Ecology, 86(1), pp. 98-107. [https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.12604 doi: 10.1111/1365-2656.12604] [//www.enviro.wiki/images/5/5d/Smith2017.pdf Article pdf]</ref>. | ||

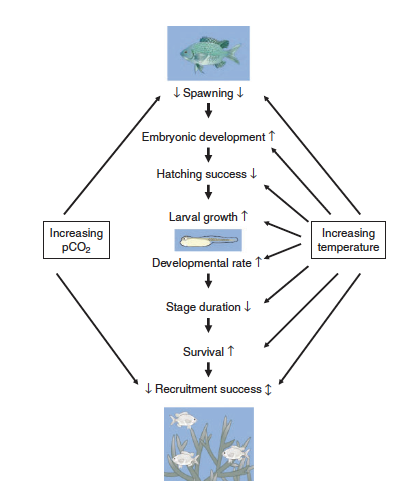

| + | [[File:PowersFig2.png|thumb|900px|right| Figure 2. Conceptual diagram showing how increased water temperatures and pCO₂ (partial pressure of carbon dioxide) affect the early life stages of fish. Where arrow direction indicated increasing rate ( ↑ ), decreasing rate ( ↓ ), or both directions depending on other environmental variables ( ↕️ ). Figure is from Pankhurst and Munday (2011)<ref name=":4" />.]] | ||

| + | ==The influence of climate change on wildlife and habitats== | ||

| + | Climate change effects on wildlife include increases and changes in disease and pathogens distribution, patterns, and outbreaks in wildlife<ref>Bradley, B. A., Wilcove, D. S., and Oppenheimer, M., 2010. Climate change increases risk of plant invasion in the Eastern United States. Biological Invasions, 12, pp.1855-1872. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-009-9597-y doi: 10.1007/s10530-009-9597-y]</ref><ref>Cudmore, T. J., Björklund, N., Carroll, A. L., and Lindgren, B. S., 2010. Climate change and the range expansion of an aggressive bark beetle: evidence of higher beetle reproduction in naïve host tree populations. Journal of Applied Ecology, 47(5), pp. 1036-1043. [https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2010.01848.x doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2664.2010.01848.x] [//www.enviro.wiki/images/b/b3/Cudmore2010.pdf Article pdf]</ref><ref>Price, S. J., Leung, W. T., Owen, C. J., Puschendorf, R., Sergeant, C., Cunningham, A. A., Balloux, F., Garner, T. W., and Nichols, R. A., 2019. Effects of historic and projected climate change on the range and impacts of an emerging wildlife disease. Global Change Biology, 25(8), pp. 2648-2660. [https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14651 doi: 10.1111/gcb.14651]</ref>; changes in range distributions and shifts in latitudinal and elevational gradients; changes in phenology or the timing of life cycle events that may create phenological mismatches<ref>Renner, S. S., and Zohner, C. M., 2018. Climate Change and Phenological Mismatch in Trophic Interactions Among Plants, Insects, and Vertebrates. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 49, pp. 165-182. [https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110617-062535 doi: 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110617-062535]</ref>; and extinction or population reduction<ref name=":2">Urban, M. C., 2015. Accelerating extinction risk from climate change. Science, 348(6234), pp. 571-573. [https://doi.org/ 10.1126/science.aaa4984 doi: 10.1126/science.aaa4984] [//www.enviro.wiki/images/1/15/Urban2015.pdf Article pdf]</ref>. The effects of climate change across a species’ range will most likely not be homogenous, meaning it can vary substantially, especially if a species’ range spans across different continents as exhibited by many migratory birds. Other changes in habitat include shifting vegetation (i.e., tree-lines are shifting to higher elevations), changes in nutrients in plants, earlier snowmelt and run-off, increase in invasive species, warming of streams and rivers, reduction or degradation of habitat (i.e., glacial melt), and an increase in large wildfires<ref>Barbero, R., Abatzoglou, J. T., Larkin, N. K., Kolden, C. A., and Stocks, B., 2015. Climate change presents increased potential for very large fires in the contiguous United States. International Journal of Wildland Fire, 24(7), pp. 892-899. [https://doi.org/10.1071/WF150830128 doi: 10.1071/WF150830128] [//www.enviro.wiki/images/0/08/Barbero2015.pdf Article pdf]</ref>and droughts<ref>Schlaepfer, D. R., Bradford, J. B., Lauenroth, W. K., Munson, S. M., Tietjen, B., Hall, S. A., Wilson, S. D., Duniway, M. C., Jia, G., Pyke, D. A., Lkhagva, A., and Jamiyansharav, K., 2017. Climate change reduces extent of temperate drylands and intensifies drought in deep soils. Nature Communications, 8, pp. 14196. [https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14196 doi: 10.1038/ncomms14196]</ref>. | ||

| − | == | + | Although climate change effects on wildlife often are linked to species-specific traits, there are general impacts associated with taxonomic groups<ref name=":1" />. For fish it can affect reproduction<ref name=":4">Pankhurst, N. W., and Munday, P. L., 2011. Effects of climate change on fish reproduction and early life history stages. Marine and Freshwater Research, 62(9), pp. 1015-1026. [https://doi.org/10.1071/MF10269 doi: 10.1071/MF10269] [[Special:FilePath/Pankhurst2011.pdf| Article pdf]]</ref>, growth, and recruitment<ref name=":3">Lynch, A. J., Myers, B. J. E., Chu, C., Eby, L. A., Falke, J. A., Kovach, R. P., Krabbenhoft, T. J., Kwak, T. J., Lyons, J., Paukert, C. P., and Whitney, J. E., 2016. Climate Change Effects on North American Inland Fish Populations and Assemblages. Fisheries, 41(7), pp. 346-361. [https://doi.org/10.1080/03632415.2016.1186016 doi: 10.1080/03632415.2016.1186016]</ref>(Figure 2). Cold-water fish such as inland North American species are highly affected with the warming of streams and rivers<ref name=":3" />. Amphibians are highly sensitive to their environment and changes in temperature and moisture can affect development, range, abundance, and phenology<ref>Blaustein, A.R., Walls, S.C., Bancroft, B.A., Lawler, J.J., Searle, C.L., and Gervasi, S.S., 2010. Direct and Indirect Effects of Climate Change on Amphibian Populations. Diversity, 2(2), pp. 281-313.[https://doi.org/10.3390/d2020281 doi: 10.3390/d2020281] [[Media:Blaustein 2010.pdf | Article pdf]]</ref><ref name=":1" /><ref>Ficetola, G. F., and Maiorano, L., 2016. Contrasting effects of temperature and precipitation change on amphibian phenology, abundance and performance. Oecologia, 181(3), pp. 683-693. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-016-3610-9 doi: 10.1007/s00442-016-3610-9]</ref>. In reptiles, climate change effects can alter thermoregulation patterns, affect female reproduction and in some species, change sex ratios with increasing temperature<ref name=":1" />. Furthermore, for many bird species the timing of migration and other phenological events are affected by climate change<ref>Crick, H. Q. P., 2004. The impact of climate change on birds. Ibis, 146(s1), pp. 48-56. [https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1474-919X.2004.00327.x doi: 10.1111/j.1474-919X.2004.00327.x] [//www.enviro.wiki/images/c/c9/Crick2004.pdf Article pdf]</ref>. Range shifts, growth size, and survival are linked to climate change for mammals<ref name=":1" />. Arctic marine mammals are closely linked to sea ice dynamics and a changing climate will affect these dynamics<ref>Kovacs, K. M., Lydersen, C., Overland, J. E., and Moore, S. E., 2011. Impacts of changing sea-ice conditions on Arctic marine mammals. Marine Biodiversity, 41, pp. 81-194. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s12526-010-0061-0 doi: 10.1007/s12526-010-0061-0]</ref>. Therefore, it is increasingly important for conservation and management plans to consider the effects of climate change on wildlife and habitat for the geographic location<ref>Mawdsley, J. R., O’Malley, R., and Ojima, D. S. 2009. A Review of Climate-Change Adaptations Strategies For Wildlife Management and Biodiversity Conservation. Conservation Biology, 23(5), pp. 1080-1089. [https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2009.01264.x doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2009.01264.x]</ref>. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

| + | |||

==See Also== | ==See Also== | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Latest revision as of 09:07, 25 April 2022

Climate change affects both terrestrial[1] and aquatic biomes[2] causing significant effects on ecosystem functions and biodiversity[3]. Climate change is affecting several key ecological processes and patterns that will have cascading impacts on wildlife and habitat[4]. For example, sea-level rise, changes in the timing and duration of growing seasons, and changes in primary production are mainly driven by changes to global environmental variables (e.g., temperature and atmospheric CO2). Climate-induced changes in the environment ultimately impact wildlife population abundance and distributions.

Related Article(s):

Contributor(s): Dr. Breanna F. Powers and Dr. Julie A. Heath

Key Resource(s):

- Global climate change and wildlife in North America. Wildlife Society Technical Review 04-2[4]

- Impacts of climate change on the future of biodiversity[3]

Introduction

Global climate change will affect ecosystem functions and cycles such as nutrient, hydraulic, and carbon cycles, changing aspects of environmental conditions such as temperature, soil moisture, and precipitation[6][7]. Wildlife species are adapted to their environments and changes to the environment and habitat conditions will mediate effects, either directly or indirectly, on species survival, fecundity and ultimately population persistence[8][9][10]. The ability to adapt to changing habitat conditions as a result of climate change will differ across individual species and between populations. Some wildlife species may be more vulnerable to climate change than other species (Figure 1). Vulnerability is often linked to particular life-history traits (e.g., specialized habitat needs or limited dispersal abilities, see Pacifici et al. 2015P[11] for a review on species vulnerability to climate change) or genetic composition. For example, grassland birds may be more vulnerable to changing climate than forest birds as forests can buffer change more so than grasslands[12]. Projected changes in the climate will generally have adverse effects of wildlife populations[13], though there are some species coping with climate change or benefitting from environmental change. For example, American kestrels (Falco sparverius) have shifted their breeding phenology to earlier in the year and may now raise two broods of young within a breeding season[14].

The influence of climate change on wildlife and habitats

Climate change effects on wildlife include increases and changes in disease and pathogens distribution, patterns, and outbreaks in wildlife[16][17][18]; changes in range distributions and shifts in latitudinal and elevational gradients; changes in phenology or the timing of life cycle events that may create phenological mismatches[19]; and extinction or population reduction[5]. The effects of climate change across a species’ range will most likely not be homogenous, meaning it can vary substantially, especially if a species’ range spans across different continents as exhibited by many migratory birds. Other changes in habitat include shifting vegetation (i.e., tree-lines are shifting to higher elevations), changes in nutrients in plants, earlier snowmelt and run-off, increase in invasive species, warming of streams and rivers, reduction or degradation of habitat (i.e., glacial melt), and an increase in large wildfires[20]and droughts[21].

Although climate change effects on wildlife often are linked to species-specific traits, there are general impacts associated with taxonomic groups[4]. For fish it can affect reproduction[15], growth, and recruitment[22](Figure 2). Cold-water fish such as inland North American species are highly affected with the warming of streams and rivers[22]. Amphibians are highly sensitive to their environment and changes in temperature and moisture can affect development, range, abundance, and phenology[23][4][24]. In reptiles, climate change effects can alter thermoregulation patterns, affect female reproduction and in some species, change sex ratios with increasing temperature[4]. Furthermore, for many bird species the timing of migration and other phenological events are affected by climate change[25]. Range shifts, growth size, and survival are linked to climate change for mammals[4]. Arctic marine mammals are closely linked to sea ice dynamics and a changing climate will affect these dynamics[26]. Therefore, it is increasingly important for conservation and management plans to consider the effects of climate change on wildlife and habitat for the geographic location[27].

References

- ^ Diffenbaugh, N. S. and Field, C. B., 2013. Changes in Ecologically Critical Terrestrial Climate Conditions. Science, 341(6145), pp. 486-492. doi: 10.1126/science.1237123

- ^ Hoegh-Guldberg, O., and Bruno, J. F., 2010. The Impact of Climate Change on the World’s Marine Ecosystem. Science, 328(5985), pp. 1523-1528. doi: 10.1126/science.1189930

- ^ 3.0 3.1 Bellard, C., Berteslsmeier, C., Leadley, P., Thuiller, W., and Courchamp, F., 2012. Impacts of climate change on the future of biodiversity. Ecological Letters, 15(4), pp. 365-377. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01736.x Article pdf

- ^ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Inkley, D. B., Anderson, M. G., Blaustein, A. R., Burkett, V. R., Felzer, B., Griffith, B., Price, J., and Root, T. L., 2004. Global Climate Change and Wildlife in North America. Wildlife Society Technical Review 04-2. The Wildlife Society, Bethesda, MD, 26 pp. Report pdf

- ^ 5.0 5.1 Urban, M. C., 2015. Accelerating extinction risk from climate change. Science, 348(6234), pp. 571-573. 10.1126/science.aaa4984 doi: 10.1126/science.aaa4984 Article pdf

- ^ Davidson, E. A. and Janssens, I. A., 2006. Temperature sensitivity of soil carbon decomposition and feedbacks to climate change. Nature, 440, pp. 165-173.doi: 10.1038/nature04514

- ^ Melillo, J. M., McGuire, A. D., Kicklighter, D. W., Moore, B., Vorosmarty, C. J., and Schloss, A. L., 1993. Global climate change and terrestrial net primary production. Nature, 363, pp. 234-240. doi: 10.1038/363234a0

- ^ Alig, R. J., Technical Coordinator, 2011. Effects of Climate Change on Natural Resources and Communities: A Compendium of Briefing Papers. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, General Technical Report, PNW-GTR-837, Portland, OR, 169p. doi:10.2737/PNW-GTR-837 Report pdf

- ^ Acevedo-Whitehouse, K., and Duffus, A. L. J., 2009. Effects of environmental change on wildlife health. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 364(1534), pp. 3429-3438. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0128

- ^ Milligan, S. R., Holt, W. V., and Lloyd, R., 2009. Impacts of climate change and environmental factors on reproduction and development in wildlife. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 364(1534), pp. 3313-3319. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0175 Article pdf

- ^ Pacifici, M., Foden, W., and Visconti, P., 2015. Assessing species vulnerability to climate change. Nature Climate Change 5, pp. 215-225. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2448

- ^ Jarzyna, M. A., Zuckerberg, B., Finley, A. O., and Porter, W. F., 2016. Synergistic effects of climate change and land cover: grassland birds are more vulnerable to climate change. Landscape Ecology, 31(10), pp. 2275-2290. doi: 10.1007/s10980-016-0399-1

- ^ IPCC, 2001. Climate Change 2001: Synthesis Report. A Contribution of Working Groups I, II, and III to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. R.T. Watson and the Core Writing Team (eds.). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom, and New York, NY, USA, 398p. Report pdf

- ^ Smith, S. H., Steenhof, K., McClure, C. J. W., and Heath, J. A. 2017. Earlier nesting by generalist predatory bird is associated with human responses to climate change. Journal of Animal Ecology, 86(1), pp. 98-107. doi: 10.1111/1365-2656.12604 Article pdf

- ^ 15.0 15.1 Pankhurst, N. W., and Munday, P. L., 2011. Effects of climate change on fish reproduction and early life history stages. Marine and Freshwater Research, 62(9), pp. 1015-1026. doi: 10.1071/MF10269 Article pdf

- ^ Bradley, B. A., Wilcove, D. S., and Oppenheimer, M., 2010. Climate change increases risk of plant invasion in the Eastern United States. Biological Invasions, 12, pp.1855-1872. doi: 10.1007/s10530-009-9597-y

- ^ Cudmore, T. J., Björklund, N., Carroll, A. L., and Lindgren, B. S., 2010. Climate change and the range expansion of an aggressive bark beetle: evidence of higher beetle reproduction in naïve host tree populations. Journal of Applied Ecology, 47(5), pp. 1036-1043. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2664.2010.01848.x Article pdf

- ^ Price, S. J., Leung, W. T., Owen, C. J., Puschendorf, R., Sergeant, C., Cunningham, A. A., Balloux, F., Garner, T. W., and Nichols, R. A., 2019. Effects of historic and projected climate change on the range and impacts of an emerging wildlife disease. Global Change Biology, 25(8), pp. 2648-2660. doi: 10.1111/gcb.14651

- ^ Renner, S. S., and Zohner, C. M., 2018. Climate Change and Phenological Mismatch in Trophic Interactions Among Plants, Insects, and Vertebrates. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 49, pp. 165-182. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110617-062535

- ^ Barbero, R., Abatzoglou, J. T., Larkin, N. K., Kolden, C. A., and Stocks, B., 2015. Climate change presents increased potential for very large fires in the contiguous United States. International Journal of Wildland Fire, 24(7), pp. 892-899. doi: 10.1071/WF150830128 Article pdf

- ^ Schlaepfer, D. R., Bradford, J. B., Lauenroth, W. K., Munson, S. M., Tietjen, B., Hall, S. A., Wilson, S. D., Duniway, M. C., Jia, G., Pyke, D. A., Lkhagva, A., and Jamiyansharav, K., 2017. Climate change reduces extent of temperate drylands and intensifies drought in deep soils. Nature Communications, 8, pp. 14196. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14196

- ^ 22.0 22.1 Lynch, A. J., Myers, B. J. E., Chu, C., Eby, L. A., Falke, J. A., Kovach, R. P., Krabbenhoft, T. J., Kwak, T. J., Lyons, J., Paukert, C. P., and Whitney, J. E., 2016. Climate Change Effects on North American Inland Fish Populations and Assemblages. Fisheries, 41(7), pp. 346-361. doi: 10.1080/03632415.2016.1186016

- ^ Blaustein, A.R., Walls, S.C., Bancroft, B.A., Lawler, J.J., Searle, C.L., and Gervasi, S.S., 2010. Direct and Indirect Effects of Climate Change on Amphibian Populations. Diversity, 2(2), pp. 281-313.doi: 10.3390/d2020281 Article pdf

- ^ Ficetola, G. F., and Maiorano, L., 2016. Contrasting effects of temperature and precipitation change on amphibian phenology, abundance and performance. Oecologia, 181(3), pp. 683-693. doi: 10.1007/s00442-016-3610-9

- ^ Crick, H. Q. P., 2004. The impact of climate change on birds. Ibis, 146(s1), pp. 48-56. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-919X.2004.00327.x Article pdf

- ^ Kovacs, K. M., Lydersen, C., Overland, J. E., and Moore, S. E., 2011. Impacts of changing sea-ice conditions on Arctic marine mammals. Marine Biodiversity, 41, pp. 81-194. doi: 10.1007/s12526-010-0061-0

- ^ Mawdsley, J. R., O’Malley, R., and Ojima, D. S. 2009. A Review of Climate-Change Adaptations Strategies For Wildlife Management and Biodiversity Conservation. Conservation Biology, 23(5), pp. 1080-1089. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2009.01264.x