Difference between revisions of "User:Jhurley/sandbox"

(→Developing PFAS Treatment Technologies) |

|||

| (689 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | == | + | ==Assessing Vapor Intrusion (VI) Impacts in Neighborhoods with Groundwater Contaminated by Chlorinated Volatile Organic Chemicals (CVOCs)== |

| − | + | The VI Diagnosis Toolkit<ref name="JohnsonEtAl2020">Johnson, P.C., Guo, Y., Dahlen, P., 2020. The VI Diagnosis Toolkit for Assessing Vapor Intrusion Pathways and Mitigating Impacts in Neighborhoods Overlying Dissolved Chlorinated Solvent Plumes. ESTCP Project ER-201501, Final Report. [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/a0d8bafd-c158-4742-b9fe-5f03d002af71 Project Website] [[Media: ER-201501.pdf | Final Report.pdf]]</ref> is a set of tools that can be used individually or in combination to assess vapor intrusion (VI) impacts at one or more buildings overlying regional-scale dissolved chlorinated solvent-impacted groundwater plumes. The strategic use of these tools can lead to confident and efficient neighborhood-scale VI pathway assessments. | |

| + | |||

<div style="float:right;margin:0 0 2em 2em;">__TOC__</div> | <div style="float:right;margin:0 0 2em 2em;">__TOC__</div> | ||

'''Related Article(s):''' | '''Related Article(s):''' | ||

| − | * [[ | + | *[[Vapor Intrusion (VI)]] |

| − | * [[ | + | *[[Vapor Intrusion – Sewers and Utility Tunnels as Preferential Pathways]] |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | '''Contributor(s):''' | |

| − | + | *Paul C. Johnson, Ph.D. | |

| + | *Paul Dahlen, Ph.D. | ||

| + | *Yuanming Guo, Ph.D. | ||

'''Key Resource(s):''' | '''Key Resource(s):''' | ||

| − | * | + | *The VI Diagnosis Toolkit for Assessing Vapor Intrusion Pathways and Impacts in Neighborhoods Overlying Dissolved Chlorinated Solvent Plumes, ESTCP Project ER-201501, Final Report<ref name="JohnsonEtAl2020"/> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | + | *CPM Test Guidelines: Use of Controlled Pressure Method Testing for Vapor Intrusion Pathway Assessment, ESTCP Project ER-201501, Technical Report<ref name="JohnsonEtAl2021">Johnson, P.C., Guo, Y., Dahlen, P., 2021. CPM Test Guidelines: Use of Controlled Pressure Method Testing for Vapor Intrusion Pathway Assessment. ESTCP ER-201501, Technical Report. [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/a0d8bafd-c158-4742-b9fe-5f03d002af71 Project Website] [[Media: ER-201501_Technical_Report.pdf | Technical_Report.pdf]]</ref> |

| − | * | + | *VI Diagnosis Toolkit User Guide, ESTCP Project ER-201501<ref name="JohnsonEtAl2022">Johnson, P.C., Guo, Y., and Dahlen, P., 2022. VI Diagnosis Toolkit User Guide, ESTCP ER-201501, User Guide. [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/a0d8bafd-c158-4742-b9fe-5f03d002af71 Project Website] [[Media: ER-201501_User_Guide.pdf | User_Guide.pdf]]</ref> |

| − | == | + | ==Background== |

| − | + | [[File:ChangFig2.png | thumb | 400px| Figure 1. Example of instrumentation used for OPTICS monitoring.]] | |

| − | + | [[File:ChangFig1.png | thumb | 400px| Figure 2. Schematic diagram illustrating the OPTICS methodology. High resolution in-situ data are integrated with traditional discrete sample analytical data using partial least-square regression to derive high resolution chemical contaminant concentration data series.]] | |

| − | + | Nationwide, the liability due to contaminated sediments is estimated in the trillions of dollars. Stakeholders are assessing and developing remedial strategies for contaminated sediment sites in major harbors and waterways throughout the U.S. The mobility of contaminants in surface water is a primary transport and risk mechanism<ref>Thibodeaux, L.J., 1996. Environmental Chemodynamics: Movement of Chemicals in Air, Water, and Soil, 2nd Edition, Volume 110 of Environmental Science and Technology: A Wiley-Interscience Series of Texts and Monographs. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 624 pages. ISBN: 0-471-61295-2</ref><ref>United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), 2005. Contaminated Sediment Remediation Guidance for Hazardous Waste Sites. Office of Superfund Remediation and Technology Innovation Report, EPA-540-R-05-012. [[Media: 2005-USEPA-Contaminated_Sediment_Remediation_Guidance.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref><ref>Lick, W., 2008. Sediment and Contaminant Transport in Surface Waters. CRC Press. 416 pages. [https://doi.org/10.1201/9781420059885 doi: 10.1201/9781420059885]</ref>; therefore, long-term monitoring of both particulate- and dissolved-phase contaminant concentration prior to, during, and following remedial action is necessary to document remedy effectiveness. Source control and total maximum daily load (TMDL) actions generally require costly manual monitoring of dissolved and particulate contaminant concentrations in surface water. The magnitude of cost for these actions is a strong motivation to implement efficient methods for long-term source control and remedial monitoring. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Traditional surface water monitoring requires mobilization of field teams to manually collect discrete water samples, send samples to laboratories, and await laboratory analysis so that a site evaluation can be conducted. These traditional methods are well known to have inherent cost and safety concerns and are of limited use (due to safety concerns and standby requirements for resources) in capturing the effects of episodic events (e.g., storms) that are important to consider in site risk assessment and remedy selection. Automated water samplers are commercially available but still require significant field support and costly laboratory analysis. Further, automated samplers may not be suitable for analytes with short hold-times and temperature requirements. | |

| − | |||

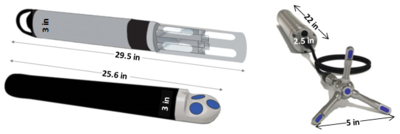

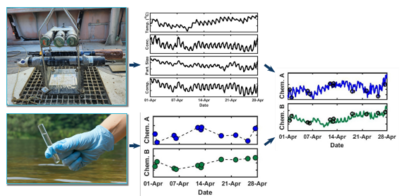

| − | + | Optically-based characterization of surface water contaminants is a cost-effective alternative to traditional discrete water sampling methods. Unlike discrete water sampling, which typically results in sparse data at low resolution, and therefore, is of limited use in determining mass loading, OPTICS (OPTically-based In-situ Characterization System) provides continuous data and allows for a complete understanding of water quality and contaminant transport in response to natural processes and human impacts<ref name="ChangEtAl2019"/><ref name="ChangEtAl2018"/><ref name="ChangEtAl2024"/><ref>Bergamaschi, B.A., Fleck, J.A., Downing, B.D., Boss, E., Pellerin, B., Ganju, N.K., Schoellhamer, D.H., Byington, A.A., Heim, W.A., Stephenson, M., Fujii, R., 2011. Methyl mercury dynamics in a tidal wetland quantified using in situ optical measurements. Limnology and Oceanography, 56(4), pp. 1355-1371. [https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2011.56.4.1355 doi: 10.4319/lo.2011.56.4.1355] [[Media: BergamaschiEtAl2011.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref><ref>Bergamaschi, B.A., Fleck, J.A., Downing, B.D., Boss, E., Pellerin, B.A., Ganju, N.K., Schoellhamer, D.H., Byington, A.A., Heim, W.A., Stephenson, M., Fujii, R., 2012. Mercury Dynamics in a San Francisco Estuary Tidal Wetland: Assessing Dynamics Using In Situ Measurements. Estuaries and Coasts, 35, pp. 1036-1048. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s12237-012-9501-3 doi: 10.1007/s12237-012-9501-3] [[Media: BergamaschiEtAl2012a.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref><ref>Bergamaschi, B.A., Krabbenhoft, D.P., Aiken, G.R., Patino, E., Rumbold, D.G., Orem, W.H., 2012. Tidally driven export of dissolved organic carbon, total mercury, and methylmercury from a mangrove-dominated estuary. Environmental Science and Technology, 46(3), pp. 1371-1378. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es2029137 doi: 10.1021/es2029137] [[Media: BergamaschiEtAl2012b.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref>. The OPTICS tool integrates commercial off-the-shelf ''in situ'' aquatic sensors (Figure 1), periodic discrete surface water sample collection, and a multi-parameter statistical prediction model<ref name="deJong1993">de Jong, S., 1993. SIMPLS: an alternative approach to partial least squares regression. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems, 18(3), pp. 251-263. [https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-7439(93)85002-X doi: 10.1016/0169-7439(93)85002-X]</ref><ref name="RosipalKramer2006">Rosipal, R. and Krämer, N., 2006. Overview and Recent Advances in Partial Least Squares, In: Subspace, Latent Structure, and Feature Selection: Statistical and Optimization Perspectives Workshop, Revised Selected Papers (Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Volume 3940), Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany. pp. 34-51. [https://doi.org/10.1007/11752790_2 doi: 10.1007/11752790_2]</ref> to provide high temporal and/or spatial resolution characterization of surface water chemicals of potential concern (COPCs) (Figure 2). | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Technology Overview== | |

| + | The principle behind OPTICS is based on the relationship between optical properties of natural waters and the particles and dissolved material contained within them<ref>Boss, E. and Pegau, W.S., 2001. Relationship of light scattering at an angle in the backward direction to the backscattering coefficient. Applied Optics, 40(30), pp. 5503-5507. [https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.40.005503 doi: 10.1364/AO.40.005503]</ref><ref>Boss, E., Twardowski, M.S., Herring, S., 2001. Shape of the particulate beam spectrum and its inversion to obtain the shape of the particle size distribution. Applied Optics, 40(27), pp. 4884-4893. [https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.40.004885 doi:10/1364/AO.40.004885]</ref><ref>Babin, M., Morel, A., Fournier-Sicre, V., Fell, F., Stramski, D., 2003. Light scattering properties of marine particles in coastal and open ocean waters as related to the particle mass concentration. Limnology and Oceanography, 48(2), pp. 843-859. [https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2003.48.2.0843 doi: 10.4319/lo.2003.48.2.0843] [[Media: BabinEtAl2003.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref><ref>Coble, P., Hu, C., Gould, R., Chang, G., Wood, M., 2004. Colored dissolved organic matter in the coastal ocean: An optical tool for coastal zone environmental assessment and management. Oceanography, 17(2), pp. 50-59. [https://doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2004.47 doi: 10.5670/oceanog.2004.47] [[Media: CobleEtAl2004.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref><ref>Sullivan, J.M., Twardowski, M.S., Donaghay, P.L., Freeman, S.A., 2005. Use of optical scattering to discriminate particle types in coastal waters. Applied Optics, 44(9), pp. 1667–1680. [https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.44.001667 doi: 10.1364/AO.44.001667]</ref><ref>Twardowski, M.S., Boss, E., Macdonald, J.B., Pegau, W.S., Barnard, A.H., Zaneveld, J.R.V., 2001. A model for estimating bulk refractive index from the optical backscattering ratio and the implications for understanding particle composition in case I and case II waters. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 106(C7), pp. 14,129-14,142. [https://doi.org/10.1029/2000JC000404 doi: 10/1029/2000JC000404] [[Media: TwardowskiEtAl2001.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref><ref>Chang, G.C., Barnard, A.H., McLean, S., Egli, P.J., Moore, C., Zaneveld, J.R.V., Dickey, T.D., Hanson, A., 2006. In situ optical variability and relationships in the Santa Barbara Channel: implications for remote sensing. Applied Optics, 45(15), pp. 3593–3604. [https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.45.003593 doi: 10.1364/AO.45.003593]</ref><ref>Slade, W.H. and Boss, E., 2015. Spectral attenuation and backscattering as indicators of average particle size. Applied Optics, 54(24), pp. 7264-7277. [https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.54.007264 doi: 10/1364/AO.54.007264] [[Media: SladeBoss2015.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref>. Surface water COPCs such as heavy metals and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are hydrophobic in nature and tend to sorb to materials in the water column, which have unique optical signatures that can be measured at high-resolution using ''in situ'', commercially available aquatic sensors<ref>Agrawal, Y.C. and Pottsmith, H.C., 2000. Instruments for particle size and settling velocity observations in sediment transport. Marine Geology, 168(1-4), pp. 89-114. [https://doi.org/10.1016/S0025-3227(00)00044-X doi: 10.1016/S0025-3227(00)00044-X]</ref><ref>Boss, E., Pegau, W.S., Gardner, W.D., Zaneveld, J.R.V., Barnard, A.H., Twardowski, M.S., Chang, G.C., Dickey, T.D., 2001. Spectral particulate attenuation and particle size distribution in the bottom boundary layer of a continental shelf. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 106(C5), pp. 9509-9516. [https://doi.org/10.1029/2000JC900077 doi: 10.1029/2000JC900077] [[Media: BossEtAl2001.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref><ref>Boss, E., Pegau, W.S., Lee, M., Twardowski, M., Shybanov, E., Korotaev, G. Baratange, F., 2004. Particulate backscattering ratio at LEO 15 and its use to study particle composition and distribution. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 109(C1), Article C01014. [https://doi.org/10.1029/2002JC001514 doi: 10.1029/2002JC001514] [[Media: BossEtAl2004.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref><ref>Briggs, N.T., Slade, W.H., Boss, E., Perry, M.J., 2013. Method for estimating mean particle size from high-frequency fluctuations in beam attenuation or scattering measurement. Applied Optics, 52(27), pp. 6710-6725. [https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.52.006710 doi: 10.1364/AO.52.006710] [[Media: BriggsEtAl2013.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref>. Therefore, high-resolution concentrations of COPCs can be accurately and robustly derived from ''in situ'' measurements using statistical methods. | ||

| − | + | The OPTICS method is analogous to the commonly used empirical derivation of total suspended solids concentration (TSS) from optical turbidity using linear regression<ref>Rasmussen, P.P., Gray, J.R., Glysson, G.D., Ziegler, A.C., 2009. Guidelines and procedures for computing time-series suspended-sediment concentrations and loads from in-stream turbidity-sensor and streamflow data. In: Techniques and Methods, Book 3: Applications of Hydraulics, Section C: Sediment and Erosion Techniques, Ch. 4. 52 pages. U.S. Geological Survey. [[Media: RasmussenEtAl2009.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref>. However, rather than deriving one response variable (TSS) from one predictor variable (turbidity), OPTICS involves derivation of one response variable (e.g., PCB concentration) from a suite of predictor variables (e.g., turbidity, temperature, salinity, and fluorescence of chlorophyll-a) using multi-parameter statistical regression. OPTICS is based on statistical correlation – similar to the turbidity-to-TSS regression technique. The method does not rely on interpolation or extrapolation. | |

| − | + | The OPTICS technique utilizes partial least-squares (PLS) regression to determine a combination of physical, optical, and water quality properties that best predicts chemical contaminant concentrations with high variance. PLS regression is a statistically based method combining multiple linear regression and principal component analysis (PCA), where multiple linear regression finds a combination of predictors that best fit a response and PCA finds combinations of predictors with large variance<ref name="deJong1993"/><ref name="RosipalKramer2006"/>. Therefore, PLS identifies combinations of multi-collinear predictors (''in situ'', high-resolution physical, optical, and water quality measurements) that have large covariance with the response values (discrete surface water chemical contaminant concentration data from samples that are collected periodically, coincident with ''in situ'' measurements). PLS combines information about the variances of both the predictors and the responses, while also considering the correlations among them. PLS therefore provides a model with reliable predictive power. | |

| − | + | OPTICS ''in situ'' measurement parameters include, but are not limited to current velocity, conductivity, temperature, depth, turbidity, dissolved oxygen, and fluorescence of chlorophyll-a and dissolved organic matter. Instrumentation for these measurements is commercially available, robust, deployable in a wide variety of configurations (e.g., moored, vessel-mounted, etc.), powered by batteries, and records data internally and/or transmits data in real-time. The physical, optical, and water quality instrumentation is compact and self-contained. The modularity and automated nature of the OPTICS measurement system enables robust, long-term, autonomous data collection for near-continuous monitoring. | |

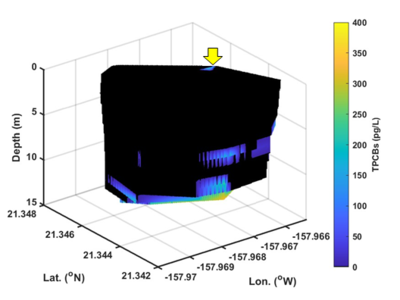

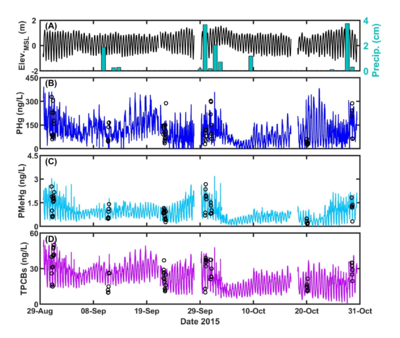

| − | + | [[File:ChangFig3.png | thumb | 400px| Figure 3. OPTICS to characterize COPC variability in the context of site processes at BCSA. (A) Tidal oscillations (Elev.<sub>MSL</sub>) and precipitation (Precip.). (B) – (D) OPTICS-derived particulate mercury (PHg) and methylmercury (PMeHg) and total PCBs (TPCBs). Open circles represent discrete water sample data.]] OPTICS measurements are provided at a significantly reduced cost relative to traditional monitoring techniques used within the environmental industry. Cost performance analysis shows that monitoring costs are reduced by more than 85% while significantly increasing the temporal and spatial resolution of sampling. The reduced cost of monitoring makes this technology suitable for a number of environmental applications including, but not limited to site baseline characterization, source control evaluation, dredge or stormflow plume characterization, and remedy performance monitoring. OPTICS has been successfully demonstrated for characterizing a wide variety of COPCs: mercury, methylmercury, copper, lead, PCBs, dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) and its related compounds (collectively, DDX), and 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD or dioxin) in a number of different environmental systems ranging from inland lakes and rivers to the coastal ocean. To date, OPTICS has been limited to surface water applications. Additional applications (e.g., groundwater) would require further research and development. | |

| − | + | ==Applications== | |

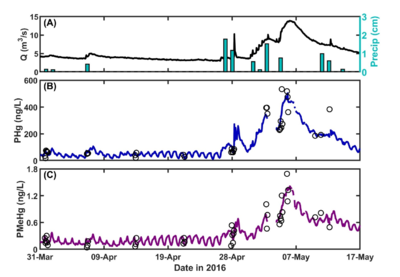

| + | [[File:ChangFig4.png | thumb | 400px| Figure 4. OPTICS reveals baseflow daily cycling and confirms storm-induced particle-bound COPC resuspension and mobilization through bank interaction. (A) Flow rate (Q) and precipitation (Precip). (B) – (C) OPTICS-derived particulate mercury (PHg) and methylmercury (PMeHg). Open circles represent discrete water sample data.]] | ||

| + | [[File:ChangFig5.png | thumb | 400px| Figure 5. Three-dimensional volume plot of high spatial resolution OPTICS-derived PCBs in exceedance of baseline showing that PCBs were discharged from the outfall (yellow arrow), remained in suspension, and dispersed elsewhere before settling.]] | ||

| + | An OPTICS study was conducted at Berry’s Creek Study Area (BCSA), New Jersey in 2014 and 2015 to understand COPC sources and transport mechanisms for development of an effective remediation plan. OPTICS successfully extended periodic discrete surface water samples to continuous, high-resolution measurements of PCBs, mercury, and methylmercury to elucidate COPC sources and transport throughout the BCSA tidal estuary system. OPTICS provided data at resolution sufficient to investigate COC variability in the context of physical processes. The results (Figure 3) facilitated focused and effective site remediation and management decisions that could not be determined based on periodic discrete samples alone, despite over seven years of monitoring at different locations throughout the system over a range of different seasons, tidal phases, and environmental conditions. The BCSA OPTICS methodology and its results have undergone official peer review overseen by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), and those results have been published in peer-reviewed literature<ref name="ChangEtAl2019"/>. | ||

| − | + | OPTICS was applied at the South River, Virginia in 2016 to quantify sources of legacy mercury in the system that are contributing to recontamination and continued elevated mercury concentrations in fish tissue. OPTICS provided information necessary to identify mechanisms for COPC redistribution and to quantify the relative contribution of each mechanism to total mass transport of mercury and methylmercury in the system. Continuous, high-resolution COPC data afforded by OPTICS helped resolve baseflow daily cycling that had never before been observed at the South River (Figure 4) and provided data at temporal resolution necessary to verify storm-induced particle-bound COC resuspension and mobilization through bank interaction. The results informed source control and remedy design and monitoring efforts. Methodology and results from the South River have been published in peer-reviewed literature<ref name="ChangEtAl2018"/>. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | The | + | The U.S. Department of Defense’s Environmental Security Technology Certification Program (ESTCP) supported an OPTICS demonstration study at the Pearl Harbor Sediment Site, Hawaii, to determine whether stormwater from Oscar 1 Pier outfall is a contributing source of PCBs to Decision Unit (DU) N-2 (ESTCP Project ER21-5021). High spatial resolution results afforded by ship-based, mobile OPTICS monitoring suggested that PCBs were discharged from the outfall, remained in suspension, and dispersed elsewhere before settling (Figure 5). More details regarding this study were presented by Chang et al. in 2024<ref name="ChangEtAl2024"/>. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Summary== | |

| + | OPTICS provides: | ||

| + | *High resolution surface water chemical contaminant characterization | ||

| + | *Cost-effective monitoring and assessment | ||

| + | *Versatile and modular monitoring with capability for real-time telemetry | ||

| + | *Data necessary for development and validation of conceptual site models | ||

| + | *A key line of evidence for designing and evaluating remedies. | ||

| − | + | Because OPTICS monitoring involves deployment of autonomous sampling instrumentation, a substantially greater volume of data can be collected using this technique compared to traditional sampling, and at a far lower cost. A large volume of data supports evaluation of chemical contaminant concentrations over a range of spatial and temporal scales, and the system can be customized for a variety of environmental applications. OPTICS helps quantify contaminant mass flux and the relative contribution of local transport and source areas to net contaminant transport. OPTICS delivers a strong line of evidence for evaluating contaminant sources, fate, and transport, and for supporting the design of a remedy tailored to address site-specific, risk-driving conditions. The improved understanding of site processes aids in the development of mitigation measures that minimize site risks. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | |||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

==See Also== | ==See Also== | ||

Latest revision as of 20:39, 15 July 2024

Assessing Vapor Intrusion (VI) Impacts in Neighborhoods with Groundwater Contaminated by Chlorinated Volatile Organic Chemicals (CVOCs)

The VI Diagnosis Toolkit[1] is a set of tools that can be used individually or in combination to assess vapor intrusion (VI) impacts at one or more buildings overlying regional-scale dissolved chlorinated solvent-impacted groundwater plumes. The strategic use of these tools can lead to confident and efficient neighborhood-scale VI pathway assessments.

Related Article(s):

Contributor(s):

- Paul C. Johnson, Ph.D.

- Paul Dahlen, Ph.D.

- Yuanming Guo, Ph.D.

Key Resource(s):

- The VI Diagnosis Toolkit for Assessing Vapor Intrusion Pathways and Impacts in Neighborhoods Overlying Dissolved Chlorinated Solvent Plumes, ESTCP Project ER-201501, Final Report[1]

- CPM Test Guidelines: Use of Controlled Pressure Method Testing for Vapor Intrusion Pathway Assessment, ESTCP Project ER-201501, Technical Report[2]

- VI Diagnosis Toolkit User Guide, ESTCP Project ER-201501[3]

Background

Nationwide, the liability due to contaminated sediments is estimated in the trillions of dollars. Stakeholders are assessing and developing remedial strategies for contaminated sediment sites in major harbors and waterways throughout the U.S. The mobility of contaminants in surface water is a primary transport and risk mechanism[4][5][6]; therefore, long-term monitoring of both particulate- and dissolved-phase contaminant concentration prior to, during, and following remedial action is necessary to document remedy effectiveness. Source control and total maximum daily load (TMDL) actions generally require costly manual monitoring of dissolved and particulate contaminant concentrations in surface water. The magnitude of cost for these actions is a strong motivation to implement efficient methods for long-term source control and remedial monitoring.

Traditional surface water monitoring requires mobilization of field teams to manually collect discrete water samples, send samples to laboratories, and await laboratory analysis so that a site evaluation can be conducted. These traditional methods are well known to have inherent cost and safety concerns and are of limited use (due to safety concerns and standby requirements for resources) in capturing the effects of episodic events (e.g., storms) that are important to consider in site risk assessment and remedy selection. Automated water samplers are commercially available but still require significant field support and costly laboratory analysis. Further, automated samplers may not be suitable for analytes with short hold-times and temperature requirements.

Optically-based characterization of surface water contaminants is a cost-effective alternative to traditional discrete water sampling methods. Unlike discrete water sampling, which typically results in sparse data at low resolution, and therefore, is of limited use in determining mass loading, OPTICS (OPTically-based In-situ Characterization System) provides continuous data and allows for a complete understanding of water quality and contaminant transport in response to natural processes and human impacts[7][8][9][10][11][12]. The OPTICS tool integrates commercial off-the-shelf in situ aquatic sensors (Figure 1), periodic discrete surface water sample collection, and a multi-parameter statistical prediction model[13][14] to provide high temporal and/or spatial resolution characterization of surface water chemicals of potential concern (COPCs) (Figure 2).

Technology Overview

The principle behind OPTICS is based on the relationship between optical properties of natural waters and the particles and dissolved material contained within them[15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22]. Surface water COPCs such as heavy metals and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are hydrophobic in nature and tend to sorb to materials in the water column, which have unique optical signatures that can be measured at high-resolution using in situ, commercially available aquatic sensors[23][24][25][26]. Therefore, high-resolution concentrations of COPCs can be accurately and robustly derived from in situ measurements using statistical methods.

The OPTICS method is analogous to the commonly used empirical derivation of total suspended solids concentration (TSS) from optical turbidity using linear regression[27]. However, rather than deriving one response variable (TSS) from one predictor variable (turbidity), OPTICS involves derivation of one response variable (e.g., PCB concentration) from a suite of predictor variables (e.g., turbidity, temperature, salinity, and fluorescence of chlorophyll-a) using multi-parameter statistical regression. OPTICS is based on statistical correlation – similar to the turbidity-to-TSS regression technique. The method does not rely on interpolation or extrapolation.

The OPTICS technique utilizes partial least-squares (PLS) regression to determine a combination of physical, optical, and water quality properties that best predicts chemical contaminant concentrations with high variance. PLS regression is a statistically based method combining multiple linear regression and principal component analysis (PCA), where multiple linear regression finds a combination of predictors that best fit a response and PCA finds combinations of predictors with large variance[13][14]. Therefore, PLS identifies combinations of multi-collinear predictors (in situ, high-resolution physical, optical, and water quality measurements) that have large covariance with the response values (discrete surface water chemical contaminant concentration data from samples that are collected periodically, coincident with in situ measurements). PLS combines information about the variances of both the predictors and the responses, while also considering the correlations among them. PLS therefore provides a model with reliable predictive power.

OPTICS in situ measurement parameters include, but are not limited to current velocity, conductivity, temperature, depth, turbidity, dissolved oxygen, and fluorescence of chlorophyll-a and dissolved organic matter. Instrumentation for these measurements is commercially available, robust, deployable in a wide variety of configurations (e.g., moored, vessel-mounted, etc.), powered by batteries, and records data internally and/or transmits data in real-time. The physical, optical, and water quality instrumentation is compact and self-contained. The modularity and automated nature of the OPTICS measurement system enables robust, long-term, autonomous data collection for near-continuous monitoring.

OPTICS measurements are provided at a significantly reduced cost relative to traditional monitoring techniques used within the environmental industry. Cost performance analysis shows that monitoring costs are reduced by more than 85% while significantly increasing the temporal and spatial resolution of sampling. The reduced cost of monitoring makes this technology suitable for a number of environmental applications including, but not limited to site baseline characterization, source control evaluation, dredge or stormflow plume characterization, and remedy performance monitoring. OPTICS has been successfully demonstrated for characterizing a wide variety of COPCs: mercury, methylmercury, copper, lead, PCBs, dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) and its related compounds (collectively, DDX), and 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD or dioxin) in a number of different environmental systems ranging from inland lakes and rivers to the coastal ocean. To date, OPTICS has been limited to surface water applications. Additional applications (e.g., groundwater) would require further research and development.

Applications

An OPTICS study was conducted at Berry’s Creek Study Area (BCSA), New Jersey in 2014 and 2015 to understand COPC sources and transport mechanisms for development of an effective remediation plan. OPTICS successfully extended periodic discrete surface water samples to continuous, high-resolution measurements of PCBs, mercury, and methylmercury to elucidate COPC sources and transport throughout the BCSA tidal estuary system. OPTICS provided data at resolution sufficient to investigate COC variability in the context of physical processes. The results (Figure 3) facilitated focused and effective site remediation and management decisions that could not be determined based on periodic discrete samples alone, despite over seven years of monitoring at different locations throughout the system over a range of different seasons, tidal phases, and environmental conditions. The BCSA OPTICS methodology and its results have undergone official peer review overseen by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), and those results have been published in peer-reviewed literature[7].

OPTICS was applied at the South River, Virginia in 2016 to quantify sources of legacy mercury in the system that are contributing to recontamination and continued elevated mercury concentrations in fish tissue. OPTICS provided information necessary to identify mechanisms for COPC redistribution and to quantify the relative contribution of each mechanism to total mass transport of mercury and methylmercury in the system. Continuous, high-resolution COPC data afforded by OPTICS helped resolve baseflow daily cycling that had never before been observed at the South River (Figure 4) and provided data at temporal resolution necessary to verify storm-induced particle-bound COC resuspension and mobilization through bank interaction. The results informed source control and remedy design and monitoring efforts. Methodology and results from the South River have been published in peer-reviewed literature[8].

The U.S. Department of Defense’s Environmental Security Technology Certification Program (ESTCP) supported an OPTICS demonstration study at the Pearl Harbor Sediment Site, Hawaii, to determine whether stormwater from Oscar 1 Pier outfall is a contributing source of PCBs to Decision Unit (DU) N-2 (ESTCP Project ER21-5021). High spatial resolution results afforded by ship-based, mobile OPTICS monitoring suggested that PCBs were discharged from the outfall, remained in suspension, and dispersed elsewhere before settling (Figure 5). More details regarding this study were presented by Chang et al. in 2024[9].

Summary

OPTICS provides:

- High resolution surface water chemical contaminant characterization

- Cost-effective monitoring and assessment

- Versatile and modular monitoring with capability for real-time telemetry

- Data necessary for development and validation of conceptual site models

- A key line of evidence for designing and evaluating remedies.

Because OPTICS monitoring involves deployment of autonomous sampling instrumentation, a substantially greater volume of data can be collected using this technique compared to traditional sampling, and at a far lower cost. A large volume of data supports evaluation of chemical contaminant concentrations over a range of spatial and temporal scales, and the system can be customized for a variety of environmental applications. OPTICS helps quantify contaminant mass flux and the relative contribution of local transport and source areas to net contaminant transport. OPTICS delivers a strong line of evidence for evaluating contaminant sources, fate, and transport, and for supporting the design of a remedy tailored to address site-specific, risk-driving conditions. The improved understanding of site processes aids in the development of mitigation measures that minimize site risks.

References

- ^ 1.0 1.1 Johnson, P.C., Guo, Y., Dahlen, P., 2020. The VI Diagnosis Toolkit for Assessing Vapor Intrusion Pathways and Mitigating Impacts in Neighborhoods Overlying Dissolved Chlorinated Solvent Plumes. ESTCP Project ER-201501, Final Report. Project Website Final Report.pdf

- ^ Johnson, P.C., Guo, Y., Dahlen, P., 2021. CPM Test Guidelines: Use of Controlled Pressure Method Testing for Vapor Intrusion Pathway Assessment. ESTCP ER-201501, Technical Report. Project Website Technical_Report.pdf

- ^ Johnson, P.C., Guo, Y., and Dahlen, P., 2022. VI Diagnosis Toolkit User Guide, ESTCP ER-201501, User Guide. Project Website User_Guide.pdf

- ^ Thibodeaux, L.J., 1996. Environmental Chemodynamics: Movement of Chemicals in Air, Water, and Soil, 2nd Edition, Volume 110 of Environmental Science and Technology: A Wiley-Interscience Series of Texts and Monographs. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 624 pages. ISBN: 0-471-61295-2

- ^ United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), 2005. Contaminated Sediment Remediation Guidance for Hazardous Waste Sites. Office of Superfund Remediation and Technology Innovation Report, EPA-540-R-05-012. Report.pdf

- ^ Lick, W., 2008. Sediment and Contaminant Transport in Surface Waters. CRC Press. 416 pages. doi: 10.1201/9781420059885

- ^ 7.0 7.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedChangEtAl2019 - ^ 8.0 8.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedChangEtAl2018 - ^ 9.0 9.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedChangEtAl2024 - ^ Bergamaschi, B.A., Fleck, J.A., Downing, B.D., Boss, E., Pellerin, B., Ganju, N.K., Schoellhamer, D.H., Byington, A.A., Heim, W.A., Stephenson, M., Fujii, R., 2011. Methyl mercury dynamics in a tidal wetland quantified using in situ optical measurements. Limnology and Oceanography, 56(4), pp. 1355-1371. doi: 10.4319/lo.2011.56.4.1355 Open Access Article

- ^ Bergamaschi, B.A., Fleck, J.A., Downing, B.D., Boss, E., Pellerin, B.A., Ganju, N.K., Schoellhamer, D.H., Byington, A.A., Heim, W.A., Stephenson, M., Fujii, R., 2012. Mercury Dynamics in a San Francisco Estuary Tidal Wetland: Assessing Dynamics Using In Situ Measurements. Estuaries and Coasts, 35, pp. 1036-1048. doi: 10.1007/s12237-012-9501-3 Open Access Article

- ^ Bergamaschi, B.A., Krabbenhoft, D.P., Aiken, G.R., Patino, E., Rumbold, D.G., Orem, W.H., 2012. Tidally driven export of dissolved organic carbon, total mercury, and methylmercury from a mangrove-dominated estuary. Environmental Science and Technology, 46(3), pp. 1371-1378. doi: 10.1021/es2029137 Open Access Article

- ^ 13.0 13.1 de Jong, S., 1993. SIMPLS: an alternative approach to partial least squares regression. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems, 18(3), pp. 251-263. doi: 10.1016/0169-7439(93)85002-X

- ^ 14.0 14.1 Rosipal, R. and Krämer, N., 2006. Overview and Recent Advances in Partial Least Squares, In: Subspace, Latent Structure, and Feature Selection: Statistical and Optimization Perspectives Workshop, Revised Selected Papers (Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Volume 3940), Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany. pp. 34-51. doi: 10.1007/11752790_2

- ^ Boss, E. and Pegau, W.S., 2001. Relationship of light scattering at an angle in the backward direction to the backscattering coefficient. Applied Optics, 40(30), pp. 5503-5507. doi: 10.1364/AO.40.005503

- ^ Boss, E., Twardowski, M.S., Herring, S., 2001. Shape of the particulate beam spectrum and its inversion to obtain the shape of the particle size distribution. Applied Optics, 40(27), pp. 4884-4893. doi:10/1364/AO.40.004885

- ^ Babin, M., Morel, A., Fournier-Sicre, V., Fell, F., Stramski, D., 2003. Light scattering properties of marine particles in coastal and open ocean waters as related to the particle mass concentration. Limnology and Oceanography, 48(2), pp. 843-859. doi: 10.4319/lo.2003.48.2.0843 Open Access Article

- ^ Coble, P., Hu, C., Gould, R., Chang, G., Wood, M., 2004. Colored dissolved organic matter in the coastal ocean: An optical tool for coastal zone environmental assessment and management. Oceanography, 17(2), pp. 50-59. doi: 10.5670/oceanog.2004.47 Open Access Article

- ^ Sullivan, J.M., Twardowski, M.S., Donaghay, P.L., Freeman, S.A., 2005. Use of optical scattering to discriminate particle types in coastal waters. Applied Optics, 44(9), pp. 1667–1680. doi: 10.1364/AO.44.001667

- ^ Twardowski, M.S., Boss, E., Macdonald, J.B., Pegau, W.S., Barnard, A.H., Zaneveld, J.R.V., 2001. A model for estimating bulk refractive index from the optical backscattering ratio and the implications for understanding particle composition in case I and case II waters. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 106(C7), pp. 14,129-14,142. doi: 10/1029/2000JC000404 Open Access Article

- ^ Chang, G.C., Barnard, A.H., McLean, S., Egli, P.J., Moore, C., Zaneveld, J.R.V., Dickey, T.D., Hanson, A., 2006. In situ optical variability and relationships in the Santa Barbara Channel: implications for remote sensing. Applied Optics, 45(15), pp. 3593–3604. doi: 10.1364/AO.45.003593

- ^ Slade, W.H. and Boss, E., 2015. Spectral attenuation and backscattering as indicators of average particle size. Applied Optics, 54(24), pp. 7264-7277. doi: 10/1364/AO.54.007264 Open Access Article

- ^ Agrawal, Y.C. and Pottsmith, H.C., 2000. Instruments for particle size and settling velocity observations in sediment transport. Marine Geology, 168(1-4), pp. 89-114. doi: 10.1016/S0025-3227(00)00044-X

- ^ Boss, E., Pegau, W.S., Gardner, W.D., Zaneveld, J.R.V., Barnard, A.H., Twardowski, M.S., Chang, G.C., Dickey, T.D., 2001. Spectral particulate attenuation and particle size distribution in the bottom boundary layer of a continental shelf. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 106(C5), pp. 9509-9516. doi: 10.1029/2000JC900077 Open Access Article

- ^ Boss, E., Pegau, W.S., Lee, M., Twardowski, M., Shybanov, E., Korotaev, G. Baratange, F., 2004. Particulate backscattering ratio at LEO 15 and its use to study particle composition and distribution. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 109(C1), Article C01014. doi: 10.1029/2002JC001514 Open Access Article

- ^ Briggs, N.T., Slade, W.H., Boss, E., Perry, M.J., 2013. Method for estimating mean particle size from high-frequency fluctuations in beam attenuation or scattering measurement. Applied Optics, 52(27), pp. 6710-6725. doi: 10.1364/AO.52.006710 Open Access Article

- ^ Rasmussen, P.P., Gray, J.R., Glysson, G.D., Ziegler, A.C., 2009. Guidelines and procedures for computing time-series suspended-sediment concentrations and loads from in-stream turbidity-sensor and streamflow data. In: Techniques and Methods, Book 3: Applications of Hydraulics, Section C: Sediment and Erosion Techniques, Ch. 4. 52 pages. U.S. Geological Survey. Open Access Article