|

|

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| − | ==PFAS Soil Remediation Technologies== | + | ==PFAS Destruction by Ultraviolet/Sulfite Treatment== |

| − | [[Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)]] are mobile in the subsurface and highly resistant to natural degradation processes, therefore soil source areas can be ongoing sources of groundwater contamination. The United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) has not promulgated soil standards for any PFAS, although a handful of states have for select compounds. Soil standards issued for protection of groundwater are in the single digit part per billion range, which is a very low threshold for soil impacts. Well developed soil treatment technologies are limited to capping, excavation with incineration or disposal, and soil stabilization with sorptive amendments. At present, no in situ destructive soil treatment technologies have been demonstrated. | + | The ultraviolet (UV)/sulfite based reductive defluorination process has emerged as an effective and practical option for generating hydrated electrons (''e<sub><small>aq</small></sub><sup><big>'''-'''</big></sup>'' ) which can destroy [[Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) | PFAS]] in water. It offers significant advantages for PFAS destruction, including significant defluorination, high treatment efficiency for long-, short-, and ultra-short chain PFAS without mass transfer limitations, selective reactivity by hydrated electrons, low energy consumption, low capital and operation costs, and no production of harmful byproducts. A UV/sulfite treatment system designed and developed by Haley and Aldrich (EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor">Haley and Aldrich, Inc. (commercial business), 2024. EradiFluor. [https://www.haleyaldrich.com/about-us/applied-research-program/eradifluor/ Comercial Website]</ref>) has been demonstrated in two field demonstrations in which it achieved near-complete defluorination and greater than 99% destruction of 40 PFAS analytes measured by EPA method 1633. |

| | <div style="float:right;margin:0 0 2em 2em;">__TOC__</div> | | <div style="float:right;margin:0 0 2em 2em;">__TOC__</div> |

| | | | |

| | '''Related Article(s):''' | | '''Related Article(s):''' |

| | | | |

| − | * [[Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)]] | + | *[[Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)]] |

| − | * [[PFAS Transport and Fate]] | + | *[[PFAS Ex Situ Water Treatment]] |

| − | * [[PFAS Sources]] | + | *[[PFAS Sources]] |

| | + | *[[PFAS Treatment by Electrical Discharge Plasma]] |

| | + | *[[Supercritical Water Oxidation (SCWO)]] |

| | + | *[[Photoactivated Reductive Defluorination - PFAS Destruction]] |

| | | | |

| − | '''Contributor(s):''' [[Jim Hatton]] and [[Bill DiGuiseppi]] | + | '''Contributors:''' John Xiong, Yida Fang, Raul Tenorio, Isobel Li, and Jinyong Liu |

| | | | |

| − | '''Key Resource(s):''' | + | '''Key Resources:''' |

| − | | + | *Defluorination of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) with Hydrated Electrons: Structural Dependence and Implications to PFAS Remediation and Management<ref name="BentelEtAl2019">Bentel, M.J., Yu, Y., Xu, L., Li, Z., Wong, B.M., Men, Y., Liu, J., 2019. Defluorination of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) with Hydrated Electrons: Structural Dependence and Implications to PFAS Remediation and Management. Environmental Science and Technology, 53(7), pp. 3718-28. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.8b06648 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b06648] [[Media: BentelEtAl2019.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref> |

| − | *[https://pfas-1.itrcweb.org/12-treatment-technologies/ ITRC Fact Sheet: Treatment Technologies, PFAS – Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances]<ref name="ITRC2020">Interstate Technology and Regulatory Council (ITRC), 2020. PFAS Technical and Regulatory Guidance Document and Fact Sheets, PFAS-1. PFAS Team, Washington, DC. [https://pfas-1.itrcweb.org/ Website] [[Media: ITRC_PFAS-1.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref>. | + | *Accelerated Degradation of Perfluorosulfonates and Perfluorocarboxylates by UV/Sulfite + Iodide: Reaction Mechanisms and System Efficiencies<ref>Liu, Z., Chen, Z., Gao, J., Yu, Y., Men, Y., Gu, C., Liu, J., 2022. Accelerated Degradation of Perfluorosulfonates and Perfluorocarboxylates by UV/Sulfite + Iodide: Reaction Mechanisms and System Efficiencies. Environmental Science and Technology, 56(6), pp. 3699-3709. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.1c07608 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.1c07608] [[Media: LiuZEtAl2022.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref> |

| − | *Persistence of Perfluoroalkyl Acid Precursors in AFFF-Impacted Groundwater and Soil<ref name="Houtz2013">Houtz, E.F., Higgins, C.P., Field, J.A., and Sedlak, D.L., 2013. Persistence of Perfluoroalkyl Acid Precursors in AFFF-Impacted Groundwater and Soil. Environmental Science and Technology, 47(15), pp. 8187−8195. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es4018877 DOI: 10.1021/es4018877]</ref>. | + | *Destruction of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Aqueous Film-Forming Foam (AFFF) with UV-Sulfite Photoreductive Treatment<ref>Tenorio, R., Liu, J., Xiao, X., Maizel, A., Higgins, C.P., Schaefer, C.E., Strathmann, T.J., 2020. Destruction of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) in Aqueous Film-Forming Foam (AFFF) with UV-Sulfite Photoreductive Treatment. Environmental Science and Technology, 54(11), pp. 6957-67. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.0c00961 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c00961]</ref> |

| | + | *EradiFluor<sup>TM</sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/> |

| | | | |

| | ==Introduction== | | ==Introduction== |

| − | PFAS are a class of highly fluorinated compounds including perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS), perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), and many other compounds with a variety of industrial and consumer uses. These compounds are often highly resistant to treatment<ref name="Kissa2001">Kissa, Erik, 2001. Fluorinated Surfactants and Repellents: Second Edition. Surfactant Science Series, Volume 97. Marcel Dekker, Inc., CRC Press, New York. 640 pages. ISBN 978-0824704728</ref> and the more mobile compounds are often problematic in groundwater systems<ref name="Backe2013">Backe, W.J., Day, T.C., and Field, J.A., 2013. Zwitterionic, Cationic, and Anionic Fluorinated Chemicals in Aqueous Film Forming Foam Formulations and Groundwater from U.S. Military Bases by Nonaqueous Large-Volume Injection HPLC-MS/MS. Environmental Science and Technology, 47(10), pp. 5226-5234. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es3034999 DOI: 10.1021/es3034999]</ref>. The US EPA has published lifetime drinking water health advisories for the combined concentration of 70 nanograms per liter (ng/L) for two common and recalcitrant PFAS: PFOS, a perfluoroalkyl sulfonic acid (PFSA), and PFOA, a perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acid (PFCA)<ref name="EPApfos2016">US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), 2016. Drinking Water Health Advisory for Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS), EPA 822-R-16-004. Office of Water, Health and Ecological Criteria Division, Washington, DC. [https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2016-05/documents/pfos_health_advisory_final-plain.pdf Free download from US EPA] [[Media: EPA822-R-16-004.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref><ref name="EPApfoa2016">US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), 2016. Drinking Water Health Advisory for Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA), EPA 822-R-16-005. Office of Water, Health and Ecological Criteria Division, Washington, DC. [https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2016-05/documents/pfoa_health_advisory_final-plain.pdf Free download from US EPA] [[Media: EPA822-R-16-005.pdf | Report]]</ref>.(See [[Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)]] for nomenclature.)

| + | The hydrated electron (''e<sub><small>aq</small></sub><sup><big>'''-'''</big></sup>'' ) can be described as an electron in solution surrounded by a small number of water molecules<ref name="BuxtonEtAl1988">Buxton, G.V., Greenstock, C.L., Phillips Helman, W., Ross, A.B., 1988. Critical Review of Rate Constants for Reactions of Hydrated Electrons, Hydrogen Atoms and Hydroxyl Radicals (⋅OH/⋅O-) in Aqueous Solution. Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data, 17(2), pp. 513-886. [https://doi.org/10.1063/1.555805 doi: 10.1063/1.555805]</ref>. Hydrated electrons can be produced by photoirradiation of solutes, including sulfite, iodide, dithionite, and ferrocyanide, and have been reported in literature to effectively decompose per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in water. The hydrated electron is one of the most reactive reducing species, with a standard reduction potential of about −2.9 volts. Though short-lived, hydrated electrons react rapidly with many species having more positive reduction potentials<ref name="BuxtonEtAl1988"/>. |

| − | | |

| − | While many of the earliest sites where these compounds were detected in groundwater were manufacturing sites, some recent detections have been attributed to fire training activities associated with aqueous film-forming foams (AFFF). AFFF is the US Department of Defense (DoD) designation for Class B firefighting foam containing PFAS, which is required for fighting fires involving petroleum liquids. Fire training areas and other source areas where AFFF was released at the surface have the potential to be ongoing sources of groundwater contamination<ref name="Houtz2013"/>. (See also [[PFAS Sources]].)

| |

| − | | |

| − | No national soil cleanup standards have been promulgated by the US EPA, although Regional Screening Levels (RSLs) have been calculated and published for perfluorobutane sulfonate (PFBS)<ref name="EPA2020">US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), 2020. Regional Screening Levels (RSLs) – User's Guide. Washington, DC. [https://www.epa.gov/risk/regional-screening-levels-rsls-users-guide Website]</ref> and data are available to calculate RSLs for PFOA and PFOS<ref name="ITRCwNs2020">Interstate Technology Regulatory Council (ITRC), 2020. PFAS Water and Soil Values Table. PFAS – Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances: PFAS Fact Sheets. [https://pfas-1.itrcweb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/ITRCPFASWaterandSoilValuesTables_NOV-2020-FINAL.xlsx Free download.] [[Media: ITRCPFASWaterandSoilTables2020.xlsx | 2020 Water and Soil Tables (excel file)]]</ref>. Several states have promulgated standards<ref name="AKDEC2020">Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation (AK DEC), 2020. 18 AAC 75, Oil and Other Hazardous Substances Pollution Control. Anchorage, AK. [https://dec.alaska.gov/media/1055/18-aac-75.pdf Free download.] [[Media: AKDEC2020_18aac75.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref> or screening levels<ref name="MEDEP2018">Maine Department of Environmental Protection (ME DEP), 2018. Maine Remedial Action Guidelines (RAGs) for Sites Contaminated with Hazardous Substances. Augusta, ME. [https://www.maine.gov/dep/spills/publications/guidance/rags/ME-Remedial-Action-Guidelines-10-19-18cc.pdf Free download.] [[Media: MEDEP2018.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref><ref name="EGLE2020">Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE), 2020. Cleanup Criteria Requirements for Response Activity (Formerly the Part 201 Generic Cleanup Criteria and Screening Levels). Remediation and Redevelopment Division, Lansing, MI. [https://www.michigan.gov/egle/0,9429,7-135-3311_4109_9846-251790--,00.html Website]</ref><ref name="NEDEE2018">Nebraska Department of Energy and Environment (NE DEE), 2018. Voluntary Cleanup Program Remedial Goals, Table A-1: Groundwater and Soil Remediation Goals. Lincoln, NE. [http://www.deq.state.ne.us/Publica.nsf/xsp/.ibmmodres/domino/OpenAttachment/Publica.nsf/D243C2B56E34EA8486256F2700698997/Body/Attach%202-6%20Table%20A-1%20VCP%20LUT%20Sept%202018.pdf Free download.] [[Media: NDEE2018.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref><ref name="NCDEQ2020">North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality (NC DEQ), 2020. Preliminary Soil Remediation Goals (PSRG) Table. Raleigh, NC. [https://files.nc.gov/ncdeq/risk-based-remediation/1.Combined-Notes-PSRGs.pdf Free download.] [[Media: NCDEQ2020.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref><ref name="TCEQ2021">Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ), 2021. Texas Risk Reduction Program (TRRP), Tier 1 Protective Concentration Levels (PCL) Tables. [http://www.tceq.texas.gov/assets/public/remediation/trrp/2021PCL%20Tables.xlsx Free Download.] [[Media: TRRP2021PCLTables.xlsx | 2021 PCL Tables (excel file)]]</ref> for soil concentrations protective of groundwater, which are several orders of magnitude lower than direct dermal exposure guidelines. These single-digit part per billion criteria will likely drive remedial actions in PFAS source areas in the future. At present, the lack of federally promulgated standards and uncertainty about future standards causes temporary stockpiling of PFAS-impacted soils on sites with soil generated from construction or investigation activities.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==Soil Treatment==

| |

| − | Addressing recalcitrant contaminants in soil has traditionally been done through containment/capping or excavation and off-site disposal or treatment. Containment/capping may be an acceptable solution for PFAS in some locations. However, containment/capping is not considered ideal given the history of releases from engineered landfills and restrictions on use of land containing capped soils. Innovative treatment approaches for PFAS include stabilization with amendments and thermal treatment.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Excavation and Disposal===

| |

| − | Excavation and off-site disposal or treatment of PFAS-impacted soils is the only well-developed treatment technology option and may be acceptable for small quantities of soil, such as those generated during characterization activities (i.e., investigation derived waste, IDW). Disposal in non-hazardous landfills is allowable in most states. However, some landfill operators are choosing to restrict acceptance of PFAS-containing waste and soils as a protection against future liability. In addition, the US EPA and some states are considering or have designated PFOA and PFOS as hazardous substances, which would reduce the number of facilities where disposal of PFAS-contaminated soil would be allowed

| |

| − |

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | [[Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)]] are a complex family of more than 3,000 manmade fluorinated organic chemicals<ref name="Wang2017">Wang, Z., DeWitt, J.C., Higgins, C.P., and Cousins, I.T., 2017. A Never-Ending Story of Per- and Poly-Fluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs)? Environmental Science and Technology, 51(5), pp. 2508-2518. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b04806 DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.6b04806] [[Media: Wang2017.pdf | Open access article.]]</ref> although not all of these are currently in use or production. PFAS are produced using several different processes. Fluorosurfactants, which include perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs) (see [[Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) | PFAS]] article for nomenclature) and side-chain fluorinated polymers, have been manufactured using two major processes: [[Wikipedia: Electrochemical fluorination | electrochemical fluorination (ECF)]] and [[Wikipedia: Telomerization | telomerization]]<ref name="KEMI2015"/>. ECF was licensed by 3M in the 1940s<ref name="Banks1994">Banks, R.E., Smart, B.E. and Tatlow, J.C. eds., 1994. Organofluorine Chemistry: Principles and Commercial Applications. Springer Science and Business Media, New York, N. Y. [https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-1-4899-1202-2 DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4899-1202-2]</ref> and used by 3M until 2001. ECF produces a mixture of even and odd numbered carbon chain lengths of approximately 70% linear and 30% branched substances<ref name="Concawe2016">Concawe (Conservation of Clean Air and Water in Europe), 2016. Environmental fate and effects of poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Report No. 8/16. Brussels, Belgium. [[Media:Concawe2016.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref>. Telomerization was developed in the 1970s<ref name="Benskin2012a">Benskin, J.P., Ahrens, L., Muir, D.C., Scott, B.F., Spencer, C., Rosenberg, B., Tomy, G., Kylin, H., Lohmann, R. and Martin, J.W., 2012. Manufacturing Origin of Perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) in Atlantic and Canadian Arctic Seawater. Environmental Science and Technology, 46(2), pp. 677-685. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es202958p DOI: 10.1021/es202958p]</ref>, and yields mainly even numbered, straight carbon chain isomers<ref name="Kissa2001"/><ref name="Parsons2008">Parsons, J.R., Sáez, M., Dolfing, J. and De Voogt, P., 2008. Biodegradation of Perfluorinated Compounds. Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 196, pp. 53-71. Springer, New York, NY. [https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-78444-1_2 DOI: 10.1007/978-0-387-78444-1_2] Free download from: [https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Jan_Dolfing/publication/23489065_Biodegradation_of_Perfluorinated_Compounds/links/0912f5087a40c9d5df000000.pdf ResearchGate]</ref>. PFAS manufacturers have provided PFAS to secondary manufacturers for production of a vast array of industrial and consumer products.

| |

| − | | |

| − | During manufacturing, PFAS may be released into the atmosphere then redeposited on land where they can also affect surface water and groundwater, or PFAS may be discharged without treatment to wastewater treatment plants or landfills, and eventually be released into the environment by treatment systems that are not designed to mitigate PFAS (see also [[PFAS Transport and Fate]]). Industrial discharges of PFAS were unregulated for many years, but that has begun to change. In January 2016, New York became the first state in the nation to regulate PFOA as a hazardous substance followed by the regulation of PFOS in April 2016. Consumer and industrial uses of PFAS-containing products can also end up releasing PFAS into landfills and into municipal wastewater, where it may accumulate undetected in biosolids which are typically treated by land application.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==Industrial Sources==

| |

| − | PFAS are used in many industrial and consumer applications, which may have released PFAS into the environment and impacted drinking water supplies in many areas of the United States<ref name="EWG2017">Environmental Working Group (EWG) and Northeastern University Social Science Environmental Health Research Institute, 2017. Mapping A Contamination Crisis. [https://www.ewg.org/research/mapping-contamination-crisis Website]</ref>. Both in the United States (US) and abroad, primary manufacturing facilities produce PFAS and secondary manufacturing facilities use PFAS to produce goods. Environmental release mechanisms associated with these facilities include air emission and dispersion, spills, and disposal of manufacturing wastes and wastewater. Potential impacts to air, soil, sediment, surface water, stormwater, and groundwater are present not only at primary release points but potentially over the surrounding area<ref name="Shin2011">Shin, H.M., Vieira, V.M., Ryan, P.B., Detwiler, R., Sanders, B., Steenland, K., and Bartell, S.M., 2011. Environmental Fate and Transport Modeling for Perfluorooctanoic Acid Emitted from the Washington Works Facility in West Virginia. Environmental Science and Technology, 45(4), pp. 1435-1442. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es102769t DOI: 10.1021/es102769t]</ref>. Some of the potential primary and secondary sources of PFAS releases to the environment are listed here<ref name="ITRC2020"/>:

| |

| − | | |

| − | * '''Textiles and leather:''' Factory or consumer applied coating to repel water, oil, and stains. Applications include protective clothing and outerwear, umbrellas, tents, sails, architectural materials, carpets, and upholstery<ref name="Rao1994">Rao, N.S., and Baker, B.E., 1994. Textile Finishes and Fluorosurfactants. In: Organofluorine Chemistry, Banks, R.E., Smart, B.E., and Tatlow, J.C., Eds. Springer, New York. [https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-1202-2_15 DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4899-1202-2_15]</ref><ref name="Hekster2003">Hekster, F.M., Laane, R.W. and De Voogt, P., 2003. Environmental and Toxicity Effects of Perfluoroalkylated Substances. Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 179, pp. 99-121. Springer, New York, NY. [https://doi.org/10.1007/0-387-21731-2_4 DOI: 10.1007/0-387-21731-2_4]</ref><ref name="Brooke2004">Brooke, D., Footitt, A., and Nwaogu, T.A., 2004. Environmental Risk Evaluation Report: Perfluorooctanesulphonate (PFOS). Environment Agency (UK), Science Group. Free download from: [http://chm.pops.int/Portals/0/docs/from_old_website/documents/meetings/poprc/submissions/Comments_2006/sia/pfos.uk.risk.eval.report.2004.pdf The Stockholm Convention] [[Media:Brooke2004.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref><ref name="Poulsen2005">Poulsen, P.B., Jensen, A.A., and Wallström, E., 2005. More environmentally friendly alternatives to PFOS-compounds and PFOA. Danish Environmental Protection Agency, Environmental Project 1013. [[Media: Poulsen2005.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref><ref name="Prevedouros2006">Prevedouros, K., Cousins, I.T., Buck, R.C. and Korzeniowski, S.H., 2006. Sources, Fate and Transport of Perfluorocarboxylates. Environmental Science and Technology, 40(1), pp. 32-44. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es0512475 DOI: 10.1021/es0512475] Free download from: [https://www.academia.edu/download/39945519/Sources_Fate_and_Transport_of_Perfluoroc20151112-1647-19vcvbf.pdf Academia.edu]</ref><ref name="Walters2006">Walters, A., and Santillo, D., 2006. Technical Note 06/2006: Uses of Perfluorinated Substances. Greenpeace Research Laboratories. [http://www.greenpeace.to/publications/uses-of-perfluorinated-chemicals.pdf Website] [[Media: Walters2006.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref><ref name="Trudel2008">Trudel, D., Horowitz, L., Wormuth, M., Scheringer, M., Cousins, I.T. and Hungerbühler, K., 2008. Estimating Consumer Exposure to PFOS and PFOA. Risk Analysis: An International Journal, 28(2), pp. 251-269. [https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2008.01017.x DOI: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2008.01017.x]</ref><ref name="Guo2009">Guo, Z., Liu, X., Krebs, K.A. and Roache, N.F., 2009. Perfluorocarboxylic Acid Content in 116 Articles of Commerce, EPA/600/R-09/033. National Risk Management Research Laboratory, US Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC. Available from: [https://cfpub.epa.gov/si/si_public_record_report.cfm?Lab=NRMRL&dirEntryId=206124 US EPA.] [[Media: Guo2009.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref><ref name="USEPA2009">US Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), 2009. Long-Chain Perfluorinated Chemicals (PFCs), Action Plan. [https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2016-01/documents/pfcs_action_plan1230_09.pdf Website] [[Media: USEPA2009.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref><ref name="Ahrens2011a">Ahrens, L., 2011. Polyfluoroalkyl compounds in the aquatic environment: a review of their occurrence and fate. Journal of Environmental Monitoring, 13(1), pp.20-31.

| |

| − | [http://dx.doi.org/10.1039/C0EM00373E DOI: 10.1039/C0EM00373E]. Free download available from: [https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Lutz_Ahrens/publication/47622154_Polyfluoroalkyl_compounds_in_the_aquatic_environment_A_review_of_their_occurrence_and_fate/links/00b7d53762cfedaf12000000/Polyfluoroalkyl-compounds-in-the-aquatic-environment-A-review-of-their-occurrence-and-fate.pdf ResearchGate]</ref><ref name="Buck2011">Buck, R.C., Franklin, J., Berger, U., Conder, J.M., Cousins, I.T., De Voogt, P., Jensen, A.A., Kannan, K., Mabury, S.A. and van Leeuwen, S.P., 2011. Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in the Environment: Terminology, Classification, and Origins. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management, 7(4), pp. 513-541. [https://doi.org/10.1002/ieam.258 DOI: 10.1002/ieam.258] [[Media:Buck2011.pdf | Open access article.]]</ref><ref name="UNEP2011">United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP), 2011. Report of the persistent organic pollutants review committee on the work of its sixth meeting, Addendum, Guidance on alternatives to perfluorooctane sulfonic acid and its derivatives, UNEP/POPS/POPRC.6/13/Add.3/Rev.1 [http://www.pops.int/TheConvention/POPsReviewCommittee/Meetings/POPRC6/POPRC6Documents/tabid/783/ctl/Download/mid/3507/Default.aspx?id=125 Website] [[Media: UNEP2011.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref><ref name="Herzke2012">Herzke, D., Olsson, E. and Posner, S., 2012. Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in consumer products in Norway – A pilot study. Chemosphere, 88(8), pp. 980-987. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2012.03.035 DOI: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2012.03.035]</ref><ref name="Patagonia2016">Patagonia, Inc., 2016. An Update on Our DWR Problem. [https://www.patagonia.com/stories/our-dwr-problem-updated/story-17673.html Website] [[Media: Patagonia2016.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref><ref name="Kotthoff2015">Kotthoff, M., Müller, J., Jürling, H., Schlummer, M., and Fiedler, D., 2015. Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances in consumer products. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 22(19), pp. 14546-14559. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-015-4202-7 DOI: 10.1007/s11356-015-4202-7] [[Media: Kotthoff2015.pdf | Open access article.]]</ref><ref name="ATSDR2018">Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR), 2018. Toxicological Profile for Perfluoroalkyls, Draft for Public Comment. US Department of Health and Human Services. Free download from: [http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp200.pdf ATSDR] [[Media: ATSDR2018.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref>.

| |

| − | | |

| − | * '''Paper products:''' Surface coatings to repel grease and moisture. Uses include non-food paper packaging (for example, cardboard, carbonless forms, masking papers) and food-contact materials (for example, pizza boxes, fast food wrappers, microwave popcorn bags, baking papers, pet food bags)<ref name="Rao1994"/><ref name="Kissa2001"/><ref name="Hekster2003"/><ref name="Poulsen2005"/><ref name="Trudel2008"/><ref name="Buck2011"/><ref name="UNEP2011"/><ref name="Kotthoff2015"/><ref name="Schaider2017">Schaider, L.A., Balan, S.A., Blum, A., Andrews, D.Q., Strynar, M.J., Dickinson, M.E., Lunderberg, D.M., Lang, J.R., and Peaslee, G.F., 2017. Fluorinated Compounds in US Fast Food Packaging. Environmental Science and Technology Letters, 4(3), pp. 105-111. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.estlett.6b00435 DOI: 10.1021/acs.estlett.6b00435] [[Media: Schaider2017.pdf | Open access article.]]</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | * '''Metal Plating & Etching:''' Corrosion prevention, mechanical wear reduction, aesthetic enhancement, surfactant, wetting agent/fume suppressant for chrome, copper, nickel and tin electroplating, and post-plating cleaner<ref name="USEPA1996">US Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), 1996. Emission Factor Documentation for AP-42, Section 12.20. Office of Air Quality Planning and Standards, Emission Factor and Inventory Group, Research Triangle Park, NC. [[Media: USEPA1996.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref><ref name="Riordan1998">Riordan, B.J., Karamchandanl, R.T., Zitko, L.J., and Cushnie Jr., G.C., 1998. Capsule Report: Hard Chrome Fume Suppressants and Control Technologies. Center for Environmental Research Information, National Risk Management Research Laboratory, Office of Research and Development. EPA/625/R-98/002 [https://cfpub.epa.gov/si/si_public_record_Report.cfm?Lab=NRMRL&dirEntryID=115419 Website] [[Media: Riordan1998.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref><ref name="Kissa2001"/><ref name="Prevedouros2006"/><ref name="USEPA2009a">US Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), 2009. PFOS Chromium Electroplater Study. US EPA – Region 5, Chicago, IL. [[Media: USEPA2009a.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref><ref name="UNEP2011"/><ref name="OSHA2013">Occupational Safety and Health Agency (OSHA), 2013. Fact Sheet: Controlling Hexavalent Chromium Exposures during Electroplating. United States Department of Labor. [[Media: OSHA2013.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref><ref name="KEMI2015"/><ref name="DEPA2015">Danish Environmental Protection Agency, 2015. Alternatives to perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in textiles. [[Media: DEPA2015.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | * '''Wire Manufacturing:''' Coating and insulation<ref name="Kissa2001"/><ref name="vanderPutte2010">van der Putte, I., Murin, M., van Velthoven, M., and Affourtit, F., 2010. Analysis of the risks arising from the industrial use of Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and Ammonium Perfluorooctanoate (APFO) and from their use in consumer articles. Evaluation of the risk reduction measures for potential restrictions on the manufacture, placing on the market and use of PFOA and APFO. RPS Advies, Delft, The Netherlands for European Commission Enterprise and Industry Directorate-General. [https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/13037/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/pdf Website] [[Media: vanderPutte2010.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref><ref name="ASTSWMO2015">Association of State and Territorial Solid Waste Management Officials (ASTSWMO), 2015. Perfluorinated Chemicals (PFCs): Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) and Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) Information Paper. Remediation and Reuse Focus Group, Federal Facilities Research Center, Washington, D.C. Free download from: [https://clu-in.org/download/contaminantfocus/pops/POPs-ASTSWMO-PFCs-2015.pdf US EPA] [[Media:Deeb-Article_1-Table_2-L10-Provisional_Groundwater_Remediaton_Objectives_Class_I_Groundwater.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | * '''Industrial Surfactants, Resins, Molds, Plastics:''' Manufacture of plastics and fluoropolymers, rubber, and compression mold release coatings; plumbing fluxing agents; fluoroplastic coatings, composite resins, and flame retardant for polycarbonate<ref name="Kissa2001"/><ref name="Renner2001">Renner, R., 2001. Growing Concern Over Perfluorinated Chemicals. Environmental Science and Technology, 35(7), pp. 154A-160A. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es012317k DOI: 10.1021/es012317k] [[Media: Renner2001.pdf | Open access article.]]</ref><ref name="Poulsen2005"/><ref name="Fricke2005">Fricke, M. and Lahl, U., 2005. Risk Evaluation of Perfluorinated Surfactants as Contribution to the current Debate on the EU Commission’s REACH Document. Umweltwissenschaften und Schadstoff-Forschung (UWSF), 17(1), pp. 36-49. [https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03038694 DOI: 10.1007/BF03038694]</ref><ref name="Prevedouros2006"/><ref name="Skutlarek2006">Skutlarek, D., Exner, M. and Färber, H., 2006. Perfluorinated Surfactants in Surface and Drinking Waters. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 13(5), pp. 299-307. [https://doi.org/10.1065/espr2006.07.326 DOI: 10.1065/espr2006.07.326] Free download from: [https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Dirk_Skutlarek/publication/6729263_Perfluorinated_surfactants_in_surface_and_drinking_waters/links/0deec52049b9cba2e4000000.pdf ResearchGate]</ref><ref name="vanderPutte2010"/><ref name="Buck2011"/><ref name="Herzke2012"/><ref name="Kotthoff2015"/><ref name="Chemours2010">Chemours, 2010. The History of Teflon Fluoropolymers. [https://www.teflon.com/en/news-events/history Website]</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | * '''Photolithography, Semiconductor Industry:''' Photoresists, top anti-reflective coatings, bottom anti-reflective coatings, and etchants, with other uses including surfactants, wetting agents, and photo-acid generation<ref name="Choi2005">Choi, D.G., Jeong, J.H., Sim, Y.S., Lee, E.S., Kim, W.S. and Bae, B.S., 2005. Fluorinated Organic− Inorganic Hybrid Mold as a New Stamp for Nanoimprint and Soft Lithography. Langmuir, 21(21), pp. 9390-9392. [https://doi.org/10.1021/la0513205 DOI: 10.1021/la0513205]</ref><ref name="Rolland2004">Rolland, J.P., Van Dam, R.M., Schorzman, D.A., Quake, S.R., and DeSimone, J.M., 2004. Solvent-Resistant Photocurable “Liquid Teflon” for Microfluidic Device Fabrication. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 126(8), pp. 2322-2323. [https://doi.org/10.1021/ja031657y DOI: 10.1021/ja031657y]</ref><ref name="Brooke2004"/><ref name="vanderPutte2010"/><ref name="UNEP2011"/><ref name="Herzke2012"/>

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==Class B Firefighting Foams==

| |

| − | Aqueous film forming foam (AFFF) and other fluorinated Class B firefighting foams are another important source of PFAS to the environment, especially in military and aviation settings. [[Wikipedia: Firefighting foam | Class B firefighting foams]] have been used since the 1960s to extinguish flammable liquid hydrocarbon fires and for vapor suppression. These foams contain complex and variable mixtures of PFAS that act as surfactants. Fluorinated surfactants are both hydrophobic and oleophobic (oil-repelling), as well as thermally stable, chemically stable, and highly surface active<ref name="Moody1999">Moody, C.A. and Field, J.A., 1999. Determination of Perfluorocarboxylates in Groundwater Impacted by Fire-Fighting Activity. Environmental Science and Technology, 33(16), pp. 2800-2806. [https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/es981355%2B DOI: 10.1021/es981355+]</ref>. These properties make them uniquely suited to fighting hydrocarbon fuel fires. Use of fluorinated Class B foams is prevalent and is a major source of PFAS to the environment. Release to the environment typically occurs during firefighting operations, firefighter training, apparatus testing, or leakage during storage. Research into fluorine-free alternatives is underway and Congressional pressure is leading towards banning fluorinated Class B firefighting foams in the United States.

| |

| − | | |

| − | [[File: ChiangSalterBlanc1w2Fig1.png | thumb | 500px | Figure 1. Types of Class B firefighting foams. Reproduced from ITRC, 2020; original figure courtesy of S. Thomas, Wood PLC, used with permission.]]

| |

| − | When discussing the relationship between firefighting foams and sources of PFAS to the environment, the emphasis is typically on AFFF; however, many different types of Class B firefighting foams exist. These may or may not be fluorinated (contain PFAS). Class B foams are used to extinguish Class B fires, that is, those involving flammable liquids. Fluorinated Class B foams spread across the surface of the flammable liquid forming a thin film and extinguish fires by (1) excluding air from the flammable vapors, (2) suppressing vapor release, (3) physically separating the flames from the fuel source, and (4) cooling the fuel surface and surrounding metal surfaces<ref name="NationalFoam">National Foam, no date. A Firefighter’s Guide to Foam. [http://foamtechnology.us/Firefighters.pdf Website] [[Media: NationalFoam.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref>. From a PFAS perspective, Class B firefighting foams can be divided into two broad categories: fluorinated foams (that contain PFAS) and fluorine-free foams (that do not contain PFAS)<ref name="ITRC2020"/>. This distinction and examples of each type are shown in Figure 1.

| |

| − | | |

| − | AFFF was developed by the US Navy in the 1960s and in 1969, the US Department of Defense (DoD) issued military specification MIL-F-24385 listing firefighting performance requirements for all AFFF used within the US DoD<ref name="ITRC2020"/><ref name="Navy1969">US Navy, 1969. Military Specification MIL-F-24385(NAVY). Fire Extinguishing Agent, Aqueous Film Forming Foam (AFFF) Liquid Concentrate, Six Percent, for Fresh and Sea Water. Department of Defense, Hyattsville, Maryland. [https://quicksearch.dla.mil/qsDocDetails.aspx?ident_number=17270 Website] [[Media: milspecAFFF1969.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref><ref name="Navy2020">US Navy, 2020. Performance Specification MIL-PRF-24385F(SH) with Amendment 4. Fire Extinguishing Agent, Aqueous Film Forming Foam (AFFF) Liquid Concentrate for Fresh and Sea Water. Department of Defense, Washington, DC. [https://quicksearch.dla.mil/qsDocDetails.aspx?ident_number=17270 Website] [[Media: milspecAFFF2020.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref>. These performance standards are often referred to as “Mil-Spec.” Products that meet the Mil-Spec have been added to the US DoD [https://qpldocs.dla.mil/ Qualified Product Listing (QPL)]. In 2006 the US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) also began requiring that 14-CFR-139-certified commercial airports purchase Mil-Spec compliant AFFF only. Because the US DoD and FAA have been the primary purchasers of AFFF, development of AFFF product mixtures has historically been performance-driven (to comply with the Mil-Spec) rather than formula-driven (the specific PFAS mixtures utilized have varied over time and by manufacturer). Multiple manufacturers in the US and throughout the world produce or have produced AFFF concentrate<ref name="ITRC2020"/>. AFFF concentrate is or has been available in 1%, 3%, or 6% formulations, where the percentage designates the recommended percentage of concentrate to be mixed into water during application.

| |

| − | | |

| − | The specific mixtures of PFAS found in AFFF have varied by manufacturer and over time due to differences in production processes and voluntary formula changes. AFFF formulations can generally be grouped into three categories<ref name="ITRC2020"/>: | |

| − | | |

| − | * '''Legacy Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) AFFF''' This type of AFFF was manufactured exclusively by 3M under the brand name “Lightwater” from the late 1960s until 2002 using the ECF production process. They contain PFOS and perflouroalkane sulfonates (PFSAs) such as perfluorohexane sulfonate (PFHxS)<ref name="ITRC2020"/><ref name="Backe2013"/>. Legacy PFOS AFFF produced by ECF were voluntarily phased out in 2002, however, use of stockpiled product was permitted after that date<ref name="ITRC2020"/>.

| |

| − | | |

| − | * '''Legacy fluorotelomer AFFF''' This group consists of AFFF manufactured and sold in the U.S. from the 1970s until 2016 and includes all brands that were produced using a process known as fluorotelomerization (FT). The FT manufacturing process produces polyfluorinated substances that can degrade in the environment to perfluoroalkyl substances (specifically PFAAs) including Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA). Polyfluoroalkyl substances that degrade to create terminal PFAAs are referred to as “precursors” <ref name="ITRC2020"/>.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | * '''Modern fluorotelomer AFFF''' This group consists of AFFF developed in response to the USEPA 2010-2015 voluntary PFOA Stewardship Program<ref name="USEPA2018">US Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), 2018. Fact Sheet: 2010/2015 PFOA Stewardship Program. [https://www.epa.gov/assessing-and-managing-chemicals-under-tsca/fact-sheet-20102015-pfoa-stewardship-program Website]</ref>, which asked companies to commit to first reducing and then eliminating the following: PFOA, precursors that can break down to PFOA, and related chemicals from facility emissions and products. In response, manufacturers began producing only short-chain fluorosurfactants targeting fluorotelomer PFAS with 6 carbons per chain (C6), rather than the traditional long-chain fluorosurfactants (8 or more carbons per chain). These short-chain PFAS do not breakdown in the environment to PFOS or PFOA<ref name="ITRC2020"/>. Their toxicity in comparison to long-chain fluorosurfactants is a topic of current research.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | In the US, AFFF users including the US DoD (predominantly the Navy and Air Force), civilian airports, oil refineries, other petrochemical industries, and municipal fire departments<ref name="Darwin2011">Darwin, Robert L. 2011. Estimated Inventory of PFOS-based Aqueous Film Forming Foam (AFFF). Fire Fighting Foam Coalition, Inc., Arlington, VA. [[Media:Darwin2011.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref>. AFFF is used, for example, in fire fighting vehicles, in fixed fire suppression systems (including sprinklers and fixed spray systems in or at aircraft hangars, flammable liquid storage areas, engine hush houses, and fuel farms), and onboard military and commercial ships. Fluorinated Class B foams may be introduced to the environment through the following practices<ref name="ITRC2020"/>:

| |

| − | | |

| − | * low volume releases of foam concentrate during storage, transfer or operational requirements that mandate periodic equipment calibration

| |

| − | * moderate volume discharge of foam solution for apparatus testing and episodic discharge of AFFF-containing fire suppression systems within large aircraft hangars and buildings

| |

| − | * occasional, high-volume, broadcast discharge of foam solution for firefighting and fire suppression/prevention for emergency response

| |

| − | * periodic, high volume, broadcast discharge for fire training

| |

| − | * accidental leaks from foam distribution piping between storage and pumping locations, and from storage tanks and railcars

| |

| − | | |

| − | The DoD is currently replacing legacy, long-chain AFFF with modern, short-chain fluorotelomer AFFF and disposing of the legacy foams through incineration. While the PFAS included in modern fluorotelomer AFFF formulations are currently understood to be less toxic and less bioaccumulative than those used in legacy formulations, they are also environmentally persistent and can degrade to produce other PFAS that may pose environmental concerns<ref name="ITRC2020"/>. While fluorine free alternatives exist, they do not meet the current Mil-Spec<ref name="Navy2020"/> which requires that fluorine-based compounds be used. The US DoD is working to revise the Mil-Spec to allow fluorine-free foams, and several states have passed laws prohibiting the use of fluorinated Class B foams for training and prohibiting future manufacture, sale or distribution of fluorinated foams, with limited exceptions<ref name="Denton2019">Denton, Charles, 2019. Expert Focus: US states outpace EPA on PFAS firefighting foam laws. Chemical Watch. [https://chemicalwatch.com/78075/expert-focus-us-states-outpace-epa-on-pfas-firefighting-foam-laws Website]</ref> (e.g., WA Rev Code § 70.75A.005 (2019); VA § 9.1-207.1 (2019)). Additionally, a bill passed in the US Congress in 2018 directs the FAA to allow fluorine-free foams for use at commercial airports<ref name="FAA2018">FAA Reauthorization Act of 2018. US Public Law No: 115-254 (10/05/2018). [https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/302/text?r=1 Website] [[Media: FAA2018.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref>. Research into the development of Mil-Spec compliant fluorine-free foams that will be compatible with existing AFFF and supporting equipment is ongoing and includes the following:

| |

| − | | |

| − | * Novel Fluorine-Free Replacement for Aqueous Film Forming Foam (Lead investigator: Dr. Joseph Tsang, Naval Air Warfare Center Weapons Divisions) [https://serdp-estcp.org/Program-Areas/Weapons-Systems-and-Platforms/Waste-Reduction-and-Treatment-in-DoD-Operations/WP-2737 SERDP/ESTCP Project WP-2737]

| |

| − | * Fluorine-Free Aqueous Film Forming Foam (Lead investigator: Dr. John Payne, National Foam) [https://serdp-estcp.org/Program-Areas/Weapons-Systems-and-Platforms/Waste-Reduction-and-Treatment-in-DoD-Operations/WP-2738 SERDP/ESTCP Project WP-2738]

| |

| − | * Fluorine-Free Foams with Oleophobic Surfactants and Additives for Effective Pool fire Suppression (Lead investigator: Dr. Ramagopal Ananth, U.S. Naval Research Laboratory) [https://serdp-estcp.org/Program-Areas/Weapons-Systems-and-Platforms/Waste-Reduction-and-Treatment-in-DoD-Operations/WP-2739 SERDP/ESTCP Project WP-2739]

| |

| | | | |

| − | ==Wastewater Treatment Plants==

| + | Among the electron source chemicals, sulfite (SO<sub>3</sub><sup>2−</sup>) has emerged as one of the most effective and practical options for generating hydrated electrons to destroy PFAS in water. The mechanism of hydrated electron production in a sulfite solution under ultraviolet is shown in Equation 1 (UV is denoted as ''hv, SO<sub>3</sub><sup><big>'''•-'''</big></sup>'' is the sulfur trioxide radical anion): |

| − | Consumer and/or industrial uses of PFAS-containing materials results in the discharge of PFAS to industrial and municipal wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs). Conventional WWTP treatment processes remove less than 5% of PFAAs<ref name="Ahrens2011a"/><ref name="Schultz2006">Schultz, M.M., Higgins, C.P., Huset, C.A., Luthy, R.G., Barofsky, D.F., and Field, J.A., 2006. Fluorochemical Mass Flows in a Municipal Wastewater Treatment Facility. Environmental Science and Technology, 40(23), pp. 7350-7357. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es061025m DOI: 10.1021/es061025m] [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2556954/ Author Manuscript]</ref><ref name="MWRA2019">Michigan Waste and Recycling Association (MWRA), 2019. Statewide Study on Landfill Leachate PFOA and PFOS Impact on Water Resource Recovery Facility Influent, Second Revision. [[Media: MWRA2019.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref>. WWTPs, particularly those that receive industrial wastewater, are possible sources of PFAS release<ref name="Bossi2008">Bossi, R., Strand, J., Sortkjær, O. and Larsen, M.M., 2008. Perfluoroalkyl compounds in Danish wastewater treatment plants and aquatic environments. Environment International, 34(4), pp. 443-450. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2007.10.002 DOI: 10.1016/j.envint.2007.10.002] Free download from: [https://www.academia.edu/download/43968517/Perfluoroalkyl_compounds_in_Danish_waste20160321-31116-esz4d1.pdf Academia.edu]</ref><ref name="Lin2014">Lin, A.Y.C., Panchangam, S.C., Tsai, Y.T., and Yu, T.H., 2014. Occurrence of perfluorinated compounds in the aquatic environment as found in science park effluent, river water, rainwater, sediments, and biotissues. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 186(5), pp. 3265-3275. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-014-3617-9 DOI: 10.1007/s10661-014-3617-9]</ref><ref name="Ahrens2009">Ahrens, L., Felizeter, S., Sturm, R., Xie, Z. and Ebinghaus, R., 2009. Polyfluorinated compounds in waste water treatment plant effluents and surface waters along the River Elbe, Germany. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 58(9), pp.1326-1333. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2009.04.028 DOI: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2009.04.028] [[Media:Ahrens2009.pdf | Author’s manuscript]]</ref>.

| + | </br> |

| | + | ::<big>'''Equation 1:'''</big> [[File: XiongEq1.png | 200 px]] |

| | | | |

| − | Evaluation of full-scale WWTPs has indicated that conventional primary (sedimentation and clarification) and secondary (aerobic biodegradation of organic matter) treatment processes can result in changes in PFAS concentrations and classes. For example, higher concentrations of PFAAs have been observed in effluent than in influent, presumably due to transformation of precursor PFAS<ref name="Schultz2006"/>. Some data has indicated that the terminal PFAS compounds PFOS and PFOA were among the most frequently detected PFAS in wastewater<ref name="Hamid2016">Hamid, H. and Li, L., 2016. Role of wastewater treatment plant in environmental cycling of poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances. Ecocycles, 2(2), pp. 43-53. [https://doi.org/10.19040/ecocycles.v2i2.62 DOI: 10.19040/ecocycles.v2i2.62] [[Media: Hamid2016.pdf | Open access article.]]</ref>. A state-wide study in Michigan indicated that PFAS were detected in all of the samples from 42 WWTPs, including influent, effluent, and biosolids/sludge samples, and that the short-chain PFAS were more frequently detected in the liquid process flow (influent and effluent), while long-chain PFAS were more common in biosolids<ref name="EGLE2020"/>.

| + | The hydrated electron has demonstrated excellent performance in destroying PFAS such as [[Wikipedia:Perfluorooctanesulfonic acid | perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS)]], [[Wikipedia:Perfluorooctanoic acid|perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA)]]<ref>Gu, Y., Liu, T., Wang, H., Han, H., Dong, W., 2017. Hydrated Electron Based Decomposition of Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) in the VUV/Sulfite System. Science of The Total Environment, 607-608, pp. 541-48. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.06.197 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.06.197]</ref> and [[Wikipedia: GenX|GenX]]<ref>Bao, Y., Deng, S., Jiang, X., Qu, Y., He, Y., Liu, L., Chai, Q., Mumtaz, M., Huang, J., Cagnetta, G., Yu, G., 2018. Degradation of PFOA Substitute: GenX (HFPO–DA Ammonium Salt): Oxidation with UV/Persulfate or Reduction with UV/Sulfite? Environmental Science and Technology, 52(20), pp. 11728-34. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.8b02172 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b02172]</ref>. Mechanisms include cleaving carbon-to-fluorine (C-F) bonds (i.e., hydrogen/fluorine atom exchange) and chain shortening (i.e., [[Wikipedia: Decarboxylation | decarboxylation]], [[Wikipedia: Hydroxylation | hydroxylation]], [[Wikipedia: Elimination reaction | elimination]], and [[Wikipedia: Hydrolysis | hydrolysis]])<ref name="BentelEtAl2019"/>. |

| | | | |

| − | Multiple studies have found PFAS in municipal sewage sludge<ref name="Higgins2005">Higgins, C.P., Field, J.A., Criddle, C.S., and Luthy, R.G., 2005. Quantitative Determination of Perfluorochemicals in Sediments and Domestic Sludge. Environmental Science and Technology, 39 (11), pp. 3946 – 3956. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es048245p DOI: 10.1021/es048245p]</ref><ref name="EGLE2020"/>. The US EPA states that more than half of the sludge produced in the United States is applied to agricultural land as biosolids, therefore there are concerns that biosolids applications may become a potential source of PFAS to the environment<ref name="USEPA2020">US Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), 2020. Research on Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS). [https://www.epa.gov/chemical-research/research-and-polyfluoroalkyl-substances-pfas Website]</ref>. Application of biosolids as a soil amendment can potentially result in transfer of PFAS to soil, surface water and groundwater and can possibly allow PFAS to enter the food chain<ref name="Sepulvado2011">Sepulvado, J.G., Blaine, A.C., Hundal, L.S. and Higgins, C.P., 2011. Occurrence and Fate of Perfluorochemicals in Soil Following the Land Application of Municipal Biosolids. Environmental Science and Technology, 45(19), pp. 8106-8112. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es103903d DOI: 10.1021/es103903d]</ref><ref name="Lindstrom2011">Lindstrom, A.B., Strynar, M.J., Delinsky, A.D., Nakayama, S.F., McMillan, L., Libelo, E.L., Neill, M. and Thomas, L., 2011. Application of WWTP Biosolids and Resulting Perfluorinated Compound Contamination of Surface and Well Water in Decatur, Alabama, USA. Environmental Science and Technology, 45(19), pp. 8015-8021. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es1039425 DOI: 10.1021/es1039425]</ref><ref name="Blaine2013">Blaine, A.C., Rich, C.D., Hundal, L.S., Lau, C., Mills, M.A., Harris, K.M. and Higgins, C.P., 2013. Uptake of Perfluoroalkyl Acids into Edible Crops via Land Applied Biosolids: Field and Greenhouse Studies. Environmental Science and Technology, 47(24), pp.14062-14069. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es403094q DOI: 10.1021/es403094q] Free download from: [https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2019-11/documents/508_pfascropuptake.pdf US EPA]</ref><ref name="Blaine2014">Blaine, A.C., Rich, C.D., Sedlacko, E.M., Hundal, L.S., Kumar, K., Lau, C., Mills, M.A., Harris, K.M. and Higgins, C.P., 2014. Perfluoroalkyl Acid Distribution in Various Plant Compartments of Edible Crops Grown in Biosolids-Amended Soils. Environmental Science and Technology, 48(14), pp. 7858-7865. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es500016s DOI: 10.1021/es500016s] Free download from: [https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Kuldip_Kumar2/publication/263015815_Perfluoroalkyl_Acid_Distribution_in_Various_Plant_Compartments_of_Edible_Crops_Grown_in_Biosolids-Amended_soils/links/5984cb310f7e9b6c852f4f02/Perfluoroalkyl-Acid-Distribution-in-Various-Plant-Compartments-of-Edible-Crops-Grown-in-Biosolids-Amended-soils.pdf ResearchGate]</ref><ref name="Navarro2017">Navarro, I., de la Torre, A., Sanz, P., Porcel, M.Á., Pro, J., Carbonell, G. and de los Ángeles Martínez, M., 2017. Uptake of perfluoroalkyl substances and halogenated flame retardants by crop plants grown in biosolids-amended soils. Environmental Research, 152, pp. 199-206. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2016.10.018 DOI: 10.1016/j.envres.2016.10.018]</ref>. Limited studies have shown that PFAS concentrations can be elevated in surface and groundwater in the vicinity of agricultural fields that received PFAS contaminated biosolids for an extended period<ref name="Washington2010">Washington, J.W., Yoo, H., Ellington, J.J., Jenkins, T.M., and Libelo, E.L., 2010. Concentrations, Distribution, and Persistence of Perfluoroalkylates in Sludge-Applied Soils near Decatur, Alabama, USA. Environmental Science and Technology, 44(22), pp. 8390-8396. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es1003846 DOI: 10.1021/es1003846] Free download from: [https://www.researchgate.net/profile/John_Washington3/publication/47447289_Concentrations_Distribution_and_Persistence_of_Perfluoroalkylates_in_Sludge-Applied_Soils_near_Decatur_Alabama_USA/links/5e3c0184a6fdccd9658add41/Concentrations-Distribution-and-Persistence-of-Perfluoroalkylates-in-Sludge-Applied-Soils-near-Decatur-Alabama-USA.pdf ResearchGate]</ref>. The most abundant PFAS found in biosolids are the long-chain PFAS<ref name="Hamid2016"/><ref name="EGLE2020"/>. Based on the persistence and stability of long-chain PFAS and their interaction with biosolids, research is ongoing to determine PFAS leachability from biosolids and their bioavailability for uptake by plants, soil organisms, and the consumers of potentially PFAS-impacted plants and soil organisms.

| + | ==Process Description== |

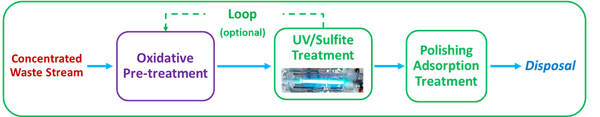

| | + | A commercial UV/sulfite treatment system designed and developed by Haley and Aldrich (EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/>) includes an optional pre-oxidation step to transform PFAS precursors (when present) and a main treatment step to break C-F bonds by UV/sulfite reduction. The effluent from the treatment process can be sent back to the influent of a pre-treatment separation system (such as a [[Wikipedia: Foam fractionation | foam fractionation]], [[PFAS Treatment by Anion Exchange | regenerable ion exchange]], or a [[Reverse Osmosis and Nanofiltration Membrane Filtration Systems for PFAS Removal | membrane filtration system]]) for further concentration or sent for off-site disposal in accordance with relevant disposal regulations. A conceptual treatment process diagram is shown in Figure 1. [[File: XiongFig1.png | thumb | left | 600 px | Figure 1: Conceptual Treatment Process for a Concentrated PFAS Stream]]<br clear="left"/> |

| | | | |

| − | ==Solid Waste Management Facilities== | + | ==Advantages== |

| − | Industrial, commercial, and consumer products containing PFAS that have been disposed in municipal solid waste (MSW) landfills or other legacy disposal areas since the 1950s are potential sources of PFAS release to the environment. Environmental and drinking water impacts from disposal of legacy PFAS-containing industrial and consumer wastes have been documented<ref name="Oliaei2010">Oliaei, F., Kriens, D. and Weber, R., 2010. Discovery and investigation of PFOS/PFCs contamination from a PFC manufacturing facility in Minnesota—environmental releases and exposure risks. Organohalogen Compd, 72, pp. 1338-1341.</ref><ref name="Shin2011"/><ref name="MDH2020">Minnesota Department of Health (MDH), 2020. Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) Sites in Minnesota. [https://www.health.state.mn.us/communities/environment/hazardous/topics/sites.html Website]</ref>.

| + | A UV/sulfite treatment system offers significant advantages for PFAS destruction compared to other technologies, including high defluorination percentage, high treatment efficiency for short-chain PFAS without mass transfer limitation, selective reactivity by ''e<sub><small>aq</small></sub><sup><big>'''-'''</big></sup>'', low energy consumption, and the production of no harmful byproducts. A summary of these advantages is provided below: |

| | + | *'''High efficiency for short- and ultrashort-chain PFAS:''' While the degradation efficiency for short-chain PFAS is challenging for some treatment technologies<ref>Singh, R.K., Brown, E., Mededovic Thagard, S., Holson, T.M., 2021. Treatment of PFAS-containing landfill leachate using an enhanced contact plasma reactor. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 408, Article 124452. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124452 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124452]</ref><ref>Singh, R.K., Multari, N., Nau-Hix, C., Woodard, S., Nickelsen, M., Mededovic Thagard, S., Holson, T.M., 2020. Removal of Poly- and Per-Fluorinated Compounds from Ion Exchange Regenerant Still Bottom Samples in a Plasma Reactor. Environmental Science and Technology, 54(21), pp. 13973-80. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.0c02158 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c02158]</ref><ref>Nau-Hix, C., Multari, N., Singh, R.K., Richardson, S., Kulkarni, P., Anderson, R.H., Holsen, T.M., Mededovic Thagard S., 2021. Field Demonstration of a Pilot-Scale Plasma Reactor for the Rapid Removal of Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances in Groundwater. American Chemical Society’s Environmental Science and Technology (ES&T) Water, 1(3), pp. 680-87. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acsestwater.0c00170 doi: 10.1021/acsestwater.0c00170]</ref>, the UV/sulfite process demonstrates excellent defluorination efficiency for both short- and ultrashort-chain PFAS, including [[Wikipedia: Trifluoroacetic acid | trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)]] and [[Wikipedia: Perfluoropropionic acid | perfluoropropionic acid (PFPrA)]]. |

| | + | *'''High defluorination ratio:''' As shown in Figure 3, the UV/sulfite treatment system has demonstrated near 100% defluorination for various PFAS under both laboratory and field conditions. |

| | + | *'''No harmful byproducts:''' While some oxidative technologies, such as electrochemical oxidation, generate toxic byproducts, including perchlorate, bromate, and chlorate, the UV/sulfite system employs a reductive mechanism and does not generate these byproducts. |

| | + | *'''Ambient pressure and low temperature:''' The system operates under ambient pressure and low temperature (<60°C), as it utilizes UV light and common chemicals to degrade PFAS. |

| | + | *'''Low energy consumption:''' The electrical energy per order values for the degradation of [[Wikipedia: Perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids | perfluorocarboxylic acids (PFCAs)]] by UV/sulfite have been reduced to less than 1.5 kilowatt-hours (kWh) per cubic meter under laboratory conditions. The energy consumption is orders of magnitude lower than that for many other destructive PFAS treatment technologies (e.g., [[Supercritical Water Oxidation (SCWO) | supercritical water oxidation]])<ref>Nzeribe, B.N., Crimi, M., Mededovic Thagard, S., Holsen, T.M., 2019. Physico-Chemical Processes for the Treatment of Per- And Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS): A Review. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology, 49(10), pp. 866-915. [https://doi.org/10.1080/10643389.2018.1542916 doi: 10.1080/10643389.2018.1542916]</ref>. |

| | + | *'''Co-contaminant destruction:''' The UV/sulfite system has also been reported effective in destroying certain co-contaminants in wastewater. For example, UV/sulfite is reported to be effective in reductive dechlorination of chlorinated volatile organic compounds, such as trichloroethene, 1,2-dichloroethane, and vinyl chloride<ref>Jung, B., Farzaneh, H., Khodary, A., Abdel-Wahab, A., 2015. Photochemical degradation of trichloroethylene by sulfite-mediated UV irradiation. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 3(3), pp. 2194-2202. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2015.07.026 doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2015.07.026]</ref><ref>Liu, X., Yoon, S., Batchelor, B., Abdel-Wahab, A., 2013. Photochemical degradation of vinyl chloride with an Advanced Reduction Process (ARP) – Effects of reagents and pH. Chemical Engineering Journal, 215-216, pp. 868-875. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2012.11.086 doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2012.11.086]</ref><ref>Li, X., Ma, J., Liu, G., Fang, J., Yue, S., Guan, Y., Chen, L., Liu, X., 2012. Efficient Reductive Dechlorination of Monochloroacetic Acid by Sulfite/UV Process. Environmental Science and Technology, 46(13), pp. 7342-49. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es3008535 doi: 10.1021/es3008535]</ref><ref>Li, X., Fang, J., Liu, G., Zhang, S., Pan, B., Ma, J., 2014. Kinetics and efficiency of the hydrated electron-induced dehalogenation by the sulfite/UV process. Water Research, 62, pp. 220-228. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2014.05.051 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2014.05.051]</ref>. |

| | | | |

| − | Several studies have identified a wide variety of PFAS in MSW landfill leachates<ref name="Busch2010">Busch, J., Ahrens, L., Sturm, R. and Ebinghaus, R., 2010. Polyfluoroalkyl compounds in landfill leachates. Environmental Pollution, 158(5), pp.1467-1471. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2009.12.031 DOI: 10.1016/j.envpol.2009.12.031]</ref><ref name="Eggen2010">Eggen, T., Moeder, M. and Arukwe, A., 2010. Municipal landfill leachates: A significant source for new and emerging pollutants. Science of the Total Environment, 408(21), pp. 5147-5157. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.07.049 DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.07.049]</ref>. PFAS composition and concentration in leachates vary depending on waste age, climate, and waste composition<ref name="Allred2015">Allred, B. M., Lang, J. R., Barlaz, M. A., and Field, J. A., 2015. Physical and Biological Release of Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) from Municipal Solid Waste in Anaerobic Model Landfill Reactors. Environmental Science and Technology, 49(13), pp. 7648-7656. [http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acs.est.5b01040 DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.5b01040]</ref><ref name="Lang2017">Lang, J.R., Allred, B.M., Field, J.A., Levis, J.W. and Barlaz, M.A., 2017. National Estimate of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substance (PFAS) Release to U.S. Municipal Landfill Leachate. Environmental Science and Technology, 51(4), pp. 2197-2205. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b05005 DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.6b05005]</ref>. The relative concentrations of various PFAS in leachate and groundwater from landfill sites is different from those found at WWTPs and AFFF-contaminated sites. In particular, 5:3 fluorotelomer carboxylic acid (FTCA) is a common and often dominant PFAS found in landfills, and has been released from carpet in model anaerobic landfill reactors. This compound could prove to be an indicator that PFAS in the environment originated from a landfill<ref name="Lang2016">Lang, J.R., Allred, B.M., Peaslee, G.F., Field, J.A., and Barlaz, M.A., 2016. Release of Per-and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) from Carpet and Clothing in Model Anaerobic Landfill Reactors. Environmental Science and Technology, 50(10), pp. 5024-5032. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.5b06237 DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.5b06237]</ref><ref name="Lang2017"/>. PFAS may also be released to the air from landfills, predominantly as fluorotelomer alcohols (FTOHs) and perfluorobutanoate (PFBA). In one study, total airborne PFAS concentrations were 5 to 30 times greater at landfills than at background reference sites<ref name="Ahrens2011b">Ahrens, L., Shoeib, M., Harner, T., Lane, D.A., Guo, R. and Reiner, E.J., 2011. Comparison of Annular Diffusion Denuder and High volume Air Samplers for Measuring Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in the Atmosphere. Analytical Chemistry, 83(24), pp. 9622-9628. [https://pubs.acs.org/doi/ DOI: 10.1021/ac202414w] Free download available from: [https://www.informea.org/sites/default/files/imported-documents/UNEP-POPS-POPRC11FU-SUBM-PFOA-Canada-2-20151211.En.pdf InforMEA]</ref>. PFAS release rates within landfills vary over time for a given waste mass, with climate (for example, rainfall) serving as the apparent driving factor for the variations<ref name="Lang2017"/><ref name="Benskin2012">Benskin, J.P., Li, B., Ikonomou, M.G., Grace, J.R. and Li, L.Y., 2012. Per-and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Landfill Leachate: Patterns, Time Trends, and Sources. Environmental Science and Technology, 46(21), pp.11532-11540. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es302471n DOI: 10.1021/es302471n]</ref>. | + | ==Limitations== |

| | + | Several environmental factors and potential issues have been identified that may impact the performance of the UV/sulfite treatment system, as listed below. Solutions to address these issues are also proposed. |

| | + | *Environmental factors, such as the presence of elevated concentrations of natural organic matter (NOM), dissolved oxygen, or nitrate, can inhibit the efficacy of UV/sulfite treatment systems by scavenging available hydrated electrons. Those interferences are commonly managed through chemical additions, reaction optimization, and/or dilution, and are therefore not considered likely to hinder treatment success. |

| | + | *Coloration in waste streams may also impact the effectiveness of the UV/sulfite treatment system by blocking the transmission of UV light, thus reducing the UV lamp's effective path length. To address this, pre-treatment may be necessary to enable UV/sulfite destruction of PFAS in the waste stream. Pre-treatment may include the use of strong oxidants or coagulants to consume or remove UV-absorbing constituents. |

| | + | *The degradation efficiency is strongly influenced by PFAS molecular structure, with fluorotelomer sulfonates (FTS) and [[Wikipedia: Perfluorobutanesulfonic acid | perfluorobutanesulfonate (PFBS)]] exhibiting greater resistance to degradation by UV/sulfite treatment compared to other PFAS compounds. |

| | | | |

| − | ==Commercial and Consumer Products== | + | ==State of the Practice== |

| − | PFAS are widely used in consumer products and household applications, with a diverse mixture of PFAS found in varying concentrations depending on the product<ref name="Clara2008">Clara, M., Scharf, S., Weiss, S., Gans, O. and Scheffknecht, C., 2008. Emissions of perfluorinated alkylated substances (PFAS) from point sources - identification of relevant branches. Water Science and Technology, 58(1), pp. 59-66. [https://doi.org/10.2166/wst.2008.641 DOI: 10.2166/wst.2008.641] [[Media:Clara2008.pdf | Open access article.]]</ref><ref name="Trier2011">Trier, X., Granby, K. and Christensen, J.H., 2011. Polyfluorinated surfactants (PFS) in paper and board coatings for food packaging. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 18(7), pp. 1108–1120. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-010-0439-3 DOI: 10.1007/s11356-010-0439-3]</ref><ref name="Fujii2013">Fujii, Y., Harada, K.H. and Koizumi, A., 2013. Occurrence of perfluorinated carboxylic acids (PFCAs) in personal care products and compounding agents. Chemosphere, 93(3), pp. 538-544. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.06.049 DOI: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.06.049]</ref><ref name="OECD2013">Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), 2013. Synthesis paper on per‐ and polyfluorinated chemicals (PFCs). OECD Environment Directorate/UNEP Global PFC Group. [https://www.oecd.org/env/ehs/risk-management/PFC_FINAL-Web.pdf Website] [[Media: OECD2013.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref><ref name="ATSDR2018"/><ref name="Kotthoff2015"/><ref name="KEMI2015"/><ref name="USEPA2016">US Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), 2016. Drinking Water Health Advisory for Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS), EPA Document Number: 822-R-16-004. Office of Water, Health and Ecological Criteria Division, Washington, DC. [https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2016-05/documents/pfos_health_advisory_final_508.pdf Website] [[Media: USEPA2016.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref>. Environmental releases associated with the commercial and consumer products are primarily related to their production. To a much lower extent, the environmental releases may be associated with the management of solid waste (for example, disposal of used items in a MSW landfill) and wastewater disposal (for example, discharge to WWTPs, private septic systems, or other subsurface disposal systems).

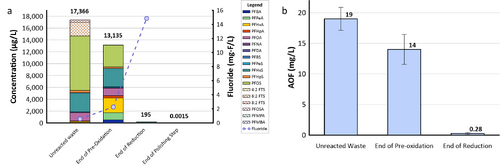

| + | [[File: XiongFig2.png | thumb | 500 px | Figure 2. Field demonstration of EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/> for PFAS destruction in a concentrated waste stream in a Mid-Atlantic Naval Air Station: a) Target PFAS at each step of the treatment shows that about 99% of PFAS were destroyed; meanwhile, the final degradation product, i.e., fluoride, increased to 15 mg/L in concentration, demonstrating effective PFAS destruction; b) AOF concentrations at each step of the treatment provided additional evidence to show near-complete mineralization of PFAS. Average results from multiple batches of treatment are shown here.]] |

| − | | + | [[File: XiongFig3.png | thumb | 500 px | Figure 3. Field demonstration of a treatment train (SAFF + EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/>) for groundwater PFAS separation and destruction at an Air Force base in California: a) Two main components of the treatment train, i.e. SAFF and EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/>; b) Results showed the effective destruction of various PFAS in the foam fractionate. The target PFAS at each step of the treatment shows that about 99.9% of PFAS were destroyed. Meanwhile, the final degradation product, i.e., fluoride, increased to 30 mg/L in concentration, demonstrating effective destruction of PFAS in a foam fractionate concentrate. After a polishing treatment step (GAC) via the onsite groundwater extraction and treatment system, all PFAS were removed to concentrations below their MCLs.]] |

| − | Studies have shown that physical degradation of some consumer products (such as PFAS-treated paper, textiles, and carpets) may release PFAS in house dust<ref name="Bjorklund2009">Björklund, J.A., Thuresson, K. and De Wit, C.A., 2009. Perfluoroalkyl Compounds (PFCs) in Indoor Dust: Concentrations, Human Exposure Estimates, and Sources. Environmental Science and Technology, 43(7), pp. 2276-2281. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es803201a DOI: 10.1021/es803201a]</ref>. Additionally, studies have also shown that professional ski wax technicians may have significant inhalation exposures to PFAS<ref name="Nilsson2013">Nilsson, H., Kärrman, A., Rotander, A., van Bavel, B., Lindström, G., and Westberg, H., 2013. Professional ski waxers' exposure to PFAS and aerosol concentrations in gas phase and different particle size fractions. Environmental Science: Processes and Impacts, 15(4), pp. 814-822. [https://doi.org/10.1039/C3EM30739E DOI: 10.1039/C3EM30739E]</ref> and snowmelt and surface waters near ski areas could have measurable PFAS impacts<ref name="Kwok2013">Kwok, K.Y., Yamazaki, E., Yamashita, N., Taniyasu, S., Murphy, M.B., Horii, Y., Petrick, G., Kallerborn, R., Kannan, K., Murano, K. and Lam, P.K., 2013. Transport of Perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) from an arctic glacier to downstream locations: Implications for sources. Science of the Total Environment, 447, pp. 46-55. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.10.091 DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.10.091]</ref>.

| + | The effectiveness of UV/sulfite technology for treating PFAS has been evaluated in two field demonstrations using the EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/> system. Aqueous samples collected from the system were analyzed using EPA Method 1633, the [[Wikipedia: TOP Assay | total oxidizable precursor (TOP) assay]], adsorbable organic fluorine (AOF) method, and non-target analysis. A summary of each demonstration and their corresponding PFAS treatment efficiency is provided below. |

| − | | + | *Under the [https://serdp-estcp.mil/ Environmental Security Technology Certification Program (ESTCP)] [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/4c073623-e73e-4f07-a36d-e35c7acc75b6/er21-5152-project-overview Project ER21-5152], a field demonstration of EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/> was conducted at a Navy site on the east coast, and results showed that the technology was highly effective in destroying various PFAS in a liquid concentrate produced from an ''in situ'' foam fractionation groundwater treatment system. As shown in Figure 2a, total PFAS concentrations were reduced from 17,366 micrograms per liter (µg/L) to 195 µg/L at the end of the UV/sulfite reaction, representing 99% destruction. After the ion exchange resin polishing step, all residual PFAS had been removed to the non-detect level, except one compound (PFOS) reported as 1.5 nanograms per liter (ng/L), which is below the current Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) of 4 ng/L. Meanwhile, the fluoride concentration increased up to 15 milligrams per liter (mg/L), confirming near complete defluorination. Figure 2b shows the adsorbable organic fluorine results from the same treatment test, which similarly demonstrates destruction of 99% of PFAS. |

| − | As increased environmental sampling for PFAS occurs, additional information will become available to further our understanding of the major and minor PFAS contributors to the environment.

| + | *Another field demonstration was completed at an Air Force base in California, where a treatment train combining [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/263f9b50-8665-4ecc-81bd-d96b74445ca2 Surface Active Foam Fractionation (SAFF)] and EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/> was used to treat PFAS in groundwater. As shown in Figure 3, PFAS analytical data and fluoride results demonstrated near-complete destruction of various PFAS. In addition, this demonstration showed: a) high PFAS destruction ratio was achieved in the foam fractionate, even in very high concentration (up to 1,700 mg/L of booster), and b) the effluent from EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/> was sent back to the influent of the SAFF system for further concentration and treatment, resulting in a closed-loop treatment system and no waste discharge from EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/>. This field demonstration was conducted with the approval of three regulatory agencies (United States Environmental Protection Agency, California Regional Water Quality Control Board, and California Department of Toxic Substances Control). |

| − | <br clear="left" /> | |

| | | | |

| | ==References== | | ==References== |

| − |

| |

| | <references /> | | <references /> |

| | | | |

| | ==See Also== | | ==See Also== |

| − |

| |

| − | *

| |