|

|

| (645 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) |

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| − | ==Downscaled High Resolution Datasets for Climate Change Projections== | + | ==Sediment Porewater Dialysis Passive Samplers for Inorganics (Peepers)== |

| − | Global climate models (GCMs) have generated projections of temperature, precipitation and other important climate change parameters with spatial resolutions of 100 to 300 km. However, higher spatial resolution information is required to assess threats to individual installations or regions. A variety of “downscaling” approaches have been used to produce high spatial resolution output (datasets) from the global climate models at scales that are useful for evaluating potential threats to critical infrastructure at regional and local scales. These datasets enable development of information about projections produced from various climate models, about downscaling to achieve desired locational specificity, and about selecting the appropriate dataset(s) to use for performing specific assessments. This article describes how these datasets can be accessed and used to evaluate potential climate change impacts.

| + | Sediment porewater dialysis passive samplers, also known as “peepers,” are sampling devices that allow the measurement of dissolved inorganic ions in the porewater of a saturated sediment. Peepers function by allowing freely-dissolved ions in sediment porewater to diffuse across a micro-porous membrane towards water contained in an isolated compartment that has been inserted into sediment. Once retrieved after a deployment period, the resulting sample obtained can provide concentrations of freely-dissolved inorganic constituents in sediment, which provides measurements that can be used for understanding contaminant fate and risk. Peepers can also be used in the same manner in surface water, although this article is focused on the use of peepers in sediment. |

| | + | |

| | <div style="float:right;margin:0 0 2em 2em;">__TOC__</div> | | <div style="float:right;margin:0 0 2em 2em;">__TOC__</div> |

| | | | |

| | '''Related Article(s):''' | | '''Related Article(s):''' |

| − | * [[Climate Change Primer]]

| |

| | | | |

| − | '''Contributor(s):''' [[Dr. Rao Kotamarthi]] | + | *[[Contaminated Sediments - Introduction]] |

| | + | *[[Contaminated Sediment Risk Assessment]] |

| | + | *[[In Situ Treatment of Contaminated Sediments with Activated Carbon]] |

| | + | *[[Passive Sampling of Munitions Constituents]] |

| | + | *[[Sediment Capping]] |

| | + | *[[Mercury in Sediments]] |

| | + | *[[Passive Sampling of Sediments]] |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | '''Contributor(s):''' |

| | + | |

| | + | *Florent Risacher, M.Sc. |

| | + | *Jason Conder, Ph.D. |

| | | | |

| | '''Key Resource(s):''' | | '''Key Resource(s):''' |

| − | * Use of Climate Information for Decision-Making and Impacts Research: State of our Understanding<ref name="Kotamarthi2016">Kotamarthi, R., Mearns, L., Hayhoe, K., Castro, C.L., and Wuebble, D., 2016. Use of Climate Information for Decision-Making and Impacts Research: State of Our Understanding. Department of Defense, Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program (SERDP), 55pp. Free download from: [https://www.serdp-estcp.org/content/download/38568/364489/file/Use_of_Climate_Information_for_Decision-Making_Technical_Report.pdf SERDP-ESTCP]</ref>

| |

| | | | |

| − | * Applying Climate Change Information to Hydrologic and Coastal Design of Transportation Infrastructure, Design Practices<ref name="Kilgore2019">Kilgore, R., Thomas, W.O. Jr., Douglass, S., Webb, B., Hayhoe, K., Stoner, A., Jacobs, J.M., Thompson, D.B., Herrmann, G.R., Douglas, E., and Anderson, C., 2019. Applying Climate Change Information to Hydrologic and Coastal Design of Transportation Infrastructure, Design Practices. The National Cooperative Highway Research Program, Transportation Research Board, Project 15-61, 154 pages. Free download from: [http://onlinepubs.trb.org/Onlinepubs/nchrp/docs/NCHRP1561_DesignProcedures.pdf The Transportation Research Board]</ref> | + | *A review of peeper passive sampling approaches to measure the availability of inorganics in sediment porewater<ref>Risacher, F.F., Schneider, H., Drygiannaki, I., Conder, J., Pautler, B.G., and Jackson, A.W., 2023. A Review of Peeper Passive Sampling Approaches to Measure the Availability of Inorganics in Sediment Porewater. Environmental Pollution, 328, Article 121581. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2023.121581 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2023.121581] [[Media: RisacherEtAl2023a.pdf | Open Access Manuscript]]</ref> |

| | + | |

| | + | *Best Practices User’s Guide: Standardizing Sediment Porewater Passive Samplers for Inorganic Constituents of Concern<ref name="RisacherEtAl2023">Risacher, F.F., Nichols, E., Schneider, H., Lawrence, M., Conder, J., Sweett, A., Pautler, B.G., Jackson, W.A., Rosen, G., 2023b. Best Practices User’s Guide: Standardizing Sediment Porewater Passive Samplers for Inorganic Constituents of Concern, ESTCP ER20-5261. [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/db871313-fbc0-4432-b536-40c64af3627f Project Website] [[Media: ER20-5261BPUG.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref> |

| | + | |

| | + | *[https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/db871313-fbc0-4432-b536-40c64af3627f/er20-5261-project-overview Standardizing Sediment Porewater Passive Samplers for Inorganic Constituents of Concern, ESTCP Project ER20-5261] |

| | | | |

| − | * Statistical Downscaling and Bias Correction for Climate Research<ref name="Maraun2018">Maraun, D., and Wildmann, M., 2018. Statistical Downscaling and Bias Correction for Climate Research. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 347 pages. [https://doi.org/10.1017/9781107588783 DOI: 10.1017/9781107588783] ISBN: 978-1-107-06605-2</ref>

| + | ==Introduction== |

| | + | Biologically available inorganic constituents associated with sediment toxicity can be quantified by measuring the freely-dissolved fraction of contaminants in the porewater<ref>Conder, J.M., Fuchsman, P.C., Grover, M.M., Magar, V.S., Henning, M.H., 2015. Critical review of mercury SQVs for the protection of benthic invertebrates. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 34(1), pp. 6-21. [https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.2769 doi: 10.1002/etc.2769] [[Media: ConderEtAl2015.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref><ref name="ClevelandEtAl2017">Cleveland, D., Brumbaugh, W.G., MacDonald, D.D., 2017. A comparison of four porewater sampling methods for metal mixtures and dissolved organic carbon and the implications for sediment toxicity evaluations. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 36(11), pp. 2906-2915. [https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.3884 doi: 10.1002/etc.3884]</ref>. Classical sediment porewater analysis usually consists of collecting large volumes of bulk sediments which are then mechanically squeezed or centrifuged to produce a supernatant, or suction of porewater from intact sediment, followed by filtration and collection<ref name="GruzalskiEtAl2016">Gruzalski, J.G., Markwiese, J.T., Carriker, N.E., Rogers, W.J., Vitale, R.J., Thal, D.I., 2016. Pore Water Collection, Analysis and Evolution: The Need for Standardization. In: Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, Vol. 237, pp. 37–51. Springer. [https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-23573-8_2 doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-23573-8_2]</ref>. The extraction and measurement processes present challenges due to the heterogeneity of sediments, physical disturbance, high reactivity of some complexes, and interaction between the solid and dissolved phases, which can impact the measured concentration of dissolved inorganics<ref>Peijnenburg, W.J.G.M., Teasdale, P.R., Reible, D., Mondon, J., Bennett, W.W., Campbell, P.G.C., 2014. Passive Sampling Methods for Contaminated Sediments: State of the Science for Metals. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management, 10(2), pp. 179–196. [https://doi.org/10.1002/ieam.1502 doi: 10.1002/ieam.1502] [[Media: PeijnenburgEtAl2014.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref>. For example, sampling disturbance can affect redox conditions<ref name="TeasdaleEtAl1995">Teasdale, P.R., Batley, G.E., Apte, S.C., Webster, I.T., 1995. Pore water sampling with sediment peepers. Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 14(6), pp. 250–256. [https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-9936(95)91617-2 doi: 10.1016/0165-9936(95)91617-2]</ref><ref>Schroeder, H., Duester, L., Fabricius, A.L., Ecker, D., Breitung, V., Ternes, T.A., 2020. Sediment water (interface) mobility of metal(loid)s and nutrients under undisturbed conditions and during resuspension. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 394, Article 122543. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122543 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122543] [[Media: SchroederEtAl2020.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref>, which can lead to under or over representation of inorganic chemical concentrations relative to the true dissolved phase concentration in the sediment porewater<ref>Wise, D.E., 2009. Sampling techniques for sediment pore water in evaluation of reactive capping efficacy. Master of Science Thesis. University of New Hampshire Scholars’ Repository. 178 pages. [https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis/502 Website] [[Media: Wise2009.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref><ref name="GruzalskiEtAl2016"/>. |

| | | | |

| − | * Downscaling Techniques for High-Resolution Climate Projections: From Global Change to Local Impacts<ref name="Kotamarthi2021">Kotamarthi, R., Hayhoe, K., Wuebbles, D., Mearns, L.O., Jacobs, J. and Jurado, J., 2021. Downscaling Techniques for High-Resolution Climate Projections: From Global Change to Local Impacts. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 202 pages. [https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108601269 DOI: 10.1017/9781108601269] ISBN: 978-1-108-47375-0</ref>

| + | To address the complications with mechanical porewater sampling, passive sampling approaches for inorganics have been developed to provide a method that has a low impact on the surrounding geochemistry of sediments and sediment porewater, thus enabling more precise measurements of inorganics<ref name="ClevelandEtAl2017"/>. Sediment porewater dialysis passive samplers, also known as “peepers,” were developed more than 45 years ago<ref name="Hesslein1976">Hesslein, R.H., 1976. An in situ sampler for close interval pore water studies. Limnology and Oceanography, 21(6), pp. 912-914. [https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.1976.21.6.0912 doi: 10.4319/lo.1976.21.6.0912] [[Media: Hesslein1976.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref> and refinements to the method such as the use of reverse tracers have been made, improving the acceptance of the technology as decision making tool. |

| | | | |

| − | ==Downscaling of Global Climate Models== | + | ==Peeper Designs== |

| − | Some communities and businesses have begun to improve their resilience to climate change by building adaptation plans based on national scale climate datatsets ([https://unfccc.int/topics/adaptation-and-resilience/workstreams/national-adaptation-plans National Adaptation Plans]), regional datasets ([https://www.dec.ny.gov/docs/administration_pdf/crrafloodriskmgmtgdnc.pdf New York State Flood Risk Management Guidance]<ref name="NYDEC2020">New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, 2020. New York State Flood Risk Management Guidance for Implementation of the Community Risk and Resiliency Act. Free download from: [https://www.dec.ny.gov/docs/administration_pdf/crrafloodriskmgmtgdnc.pdf New York State] [[Media: NewYorkState2020.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref>), and datasets generated at local spatial resolutions. Resilience to the changing climate has also been identified by the US Department of Defense (DoD) as a necessary part of the installation planning and basing process ([https://media.defense.gov/2019/Jan/29/2002084200/-1/-1/1/CLIMATE-CHANGE-REPORT-2019.PDF DoD Report on Effects of a Changing Climate]<ref name="DoD2019">US Department of Defense, 2019. Report on Effects of a Changing Climate to the Department of Defense. Free download from: [https://media.defense.gov/2019/Jan/29/2002084200/-1/-1/1/CLIMATE-CHANGE-REPORT-2019.PDF DoD] [[Media: DoD2019.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref>). More than 79 installations were identified as facing potential threats from climate change. The threats faced due to changing climate include recurrent flooding, droughts, desertification, wildfires and thawing permafrost.

| + | [[File:RisacherFig1.png|thumb|300px|Figure 1. Conceptual illustration of peeper construction showing (top, left to right) the peeper cap (optional), peeper membrane and peeper chamber, and (bottom) an assembled peeper containing peeper water]] |

| | + | [[File:RisacherFig2.png | thumb |400px| Figure 2. Example of Hesslein<ref name="Hesslein1976"/> general peeper design (42 peeper chambers), from [https://www.usgs.gov/media/images/peeper-samplers USGS]]] |

| | + | [[File:RisacherFig3.png | thumb |400px| Figure 3. Peeper deployment structure to allow the measurement of metal availability in different sediment layers using five single-chamber peepers (Photo: Geosyntec Consultants)]] |

| | + | Peepers (Figure 1) are inert containers with a small volume (typically 1-100 mL) of purified water (“peeper water”) capped with a semi-permeable membrane. Peepers can be manufactured in a wide variety of formats (Figure 2, Figure 3) and deployed in in various ways. |

| | | | |

| − | Assessing the threats climate change poses at regional and local scales requires data with higher spatial resolution than is currently available from global climate models. Global-scale climate models typically have spatial resolutions of 100 to 300 km, and output from these models needs to be spatially and/or temporally disaggregated in order to be useful in performing assessments at smaller scales. The process of producing higher spatial-temporal resolution climate model output from coarser global climate model outputs is referred to as “downscaling” and results in climate change projections (datasets) at scales that are useful for evaluating potential threats to regional and local communities and businesses. These datasets provide information on temperature, precipitation and a variety of other climate variables for current and future climate conditions under various greenhouse gas (GHG) emission scenarios. There are a variety of web-based tools available for accessing these datasets to evaluate potential climate change impacts at regional and local scales.

| + | Two designs are commonly used for peepers. Frequently, the designs are close adaptations of the original multi-chamber Hesslein design<ref name="Hesslein1976"/> (Figure 2), which consists of an acrylic sampler body with multiple sample chambers machined into it. Peeper water inside the chambers is separated from the outside environment by a semi-permeable membrane, which is held in place by a top plate fixed to the sampler body using bolts or screws. An alternative design consists of single-chamber peepers constructed using a single sample vial with a membrane secured over the mouth of the vial, as shown in Figure 3, and applied in Teasdale ''et al.''<ref name="TeasdaleEtAl1995"/>, Serbst ''et al.''<ref>Serbst, J.R., Burgess, R.M., Kuhn, A., Edwards, P.A., Cantwell, M.G., Pelletier, M.C., Berry, W.J., 2003. Precision of dialysis (peeper) sampling of cadmium in marine sediment interstitial water. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 45(3), pp. 297–305. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s00244-003-0114-5 doi: 10.1007/s00244-003-0114-5]</ref>, Thomas and Arthur<ref name="ThomasArthur2010">Thomas, B., Arthur, M.A., 2010. Correcting porewater concentration measurements from peepers: Application of a reverse tracer. Limnology and Oceanography: Methods, 8(8), pp. 403–413. [https://doi.org/10.4319/lom.2010.8.403 doi: 10.4319/lom.2010.8.403] [[Media: ThomasArthur2010.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref>, Passeport ''et al.''<ref>Passeport, E., Landis, R., Lacrampe-Couloume, G., Lutz, E.J., Erin Mack, E., West, K., Morgan, S., Lollar, B.S., 2016. Sediment Monitored Natural Recovery Evidenced by Compound Specific Isotope Analysis and High-Resolution Pore Water Sampling. Environmental Science and Technology, 50(22), pp. 12197–12204. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b02961 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b02961]</ref>, and Risacher ''et al.''<ref name="RisacherEtAl2023"/>. The vial is filled with deionized water, and the membrane is held in place using the vial cap or an o-ring. Individual vials are either directly inserted into sediment or are incorporated into a support structure to allow multiple single-chamber peepers to be deployed at once over a given depth profile (Figure 3). |

| | | | |

| − | ==Methods for Downscaling== | + | ==Peepers Preparation, Deployment and Retrieval== |

| − | {| class="wikitable" style="float:right; margin-left:10px;text-align:center;"

| + | [[File:RisacherFig4.png | thumb |300px| Figure 4: Conceptual illustration of peeper passive sampling in a sediment matrix, showing peeper immediately after deployment (top) and after equilibration between the porewater and peeper chamber water (bottom)]] |

| − | |+Table 1. Two widely used methods for developing downscaled higher resolution climate model projections | + | Peepers are often prepared in laboratories but are also commercially available in a variety of designs from several suppliers. Peepers are prepared by first cleaning all materials to remove even trace levels of metals before assembly. The water contained inside the peeper is sometimes deoxygenated, and in some cases the peeper is maintained in a deoxygenated atmosphere until deployment<ref>Carignan, R., St‐Pierre, S., Gachter, R., 1994. Use of diffusion samplers in oligotrophic lake sediments: Effects of free oxygen in sampler material. Limnology and Oceanography, 39(2), pp. 468-474. [https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.1994.39.2.0468 doi: 10.4319/lo.1994.39.2.0468] [[Media: CarignanEtAl1994.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref>. However, recent studies<ref name="RisacherEtAl2023"/> have shown that deoxygenation prior to deployment does not significantly impact sampling results due to oxygen rapidly diffusing out of the peeper during deployment. Once assembled, peepers are usually shipped in a protective bag inside a hard-case cooler for protection. |

| − | |- | + | |

| − | !Dynamical Downscaling

| + | Peepers are deployed by insertion into sediment for a period of a few days to a few weeks. Insertion into the sediment can be achieved by wading to the location when the water depth is shallow, by using push poles for deeper deployments<ref name="RisacherEtAl2023"/>, or by professional divers for the deepest sites. If divers are used, an appropriate boat or ship will be required to accommodate the diver and their equipment. Whichever method is used, peepers should be attached to an anchor or a small buoy to facilitate retrieval at the end of the deployment period. |

| − | !Statistical Downscaling

| + | |

| − | |- | + | During deployment, passive sampling is achieved via diffusion of inorganics through the peeper’s semi-permeable membrane, as the enclosed volume of peeper water equilibrates with the surrounding sediment porewater (Figure 4). It is assumed that the peeper insertion does not greatly alter geochemical conditions that affect freely-dissolved inorganics. Additionally, it is assumed that the peeper water equilibrates with freely-dissolved inorganics in sediment in such a way that the concentration of inorganics in the peeper water would be equal to that of the concentration of inorganics in the sediment porewater. |

| − | |Deterministic climate change simulations that output</br>many climate variables with sub-daily information ||Primarily limited to daily temperature and precipitation

| + | |

| − | |-

| + | After retrieval, the peepers are brought to the surface and usually preserved until they can be processed. This can be achieved by storing the peepers inside a sealable, airtight bag with either inert gas or oxygen absorbing packets<ref name="RisacherEtAl2023"/>. The peeper water can then be processed by quickly pipetting it into an appropriate sample bottle which usually contains a preservative (e.g., nitric acid for metals). This step is generally conducted in the field. Samples are stored on ice to maintain a temperature of less than 4°C and shipped to an analytical laboratory. The samples are then analyzed for inorganics by standard methods (i.e., USEPA SW-846). The results obtained from the analytical laboratory are then used directly or assessed using the equations below if a reverse tracer is used because deployment time is insufficient for all analytes to reach equilibrium. |

| − | |Computationally expensive; hence, limited number of simulations – both</br>GHG emission scenarios and global climate models downscaled||Computationally efficient; hence, downscaled data typically</br>available for many different global climate models and GHG emission scenarios | |

| − | |-

| |

| − | |May require additional bias correction||Method incorporates bias correction

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | |Observational data at the downscaled location are not necessary</br>to obtain the downscaled output at the location||Best suited for locations with 30 years or more of observational data

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | |Does not assume stationarity or in other words the model</br>simulates the future regardless of what has happened in the past||Stationarity assumption - assumes that the statistical relationship between global</br>climate model and observations will remain constant in the future

| |

| − | |}

| |

| − | There are two main approaches to downscaling. One method, commonly referred to as “statistical downscaling”, uses the empirical-statistical relationships between large-scale weather phenomena and historical local weather data. In this method, these statistical relationships are applied to output generated by global climate models. A second method uses physics-based numerical models (regional-scale climate models or RCMs) of weather and climate that operate over a limited region of the earth (e.g., North America) and at spatial resolutions that are typically 3 to 10 times finer than the global-scale climate models. This method is known as “dynamical downscaling”. These regional-scale climate models are similar to the global models with respect to their reliance on the principles of physics, but because they operate over only part of the earth, they require information about what is coming in from the rest of the earth as well as what is going out of the limited region of the model. This is generally obtained from a global model. The primary differences between statistical and dynamical downscaling methods are summarized in Table 1.

| |

| | | | |

| − | It is important to realize that there is no “best” downscaling method or dataset, and that the best method/dataset for a given problem depends on that problem’s specific needs. Several data products based on downscaling higher level spatial data are available ([https://cida.usgs.gov/gdp/ USGS], [http://maca.northwestknowledge.net/ MACA], [https://www.narccap.ucar.edu/ NARCCAP], [https://na-cordex.org/ CORDEX-NA]). The appropriate method and dataset to use depends on the intended application. The method selected should be able to credibly resolve spatial and temporal scales relevant for the application. For example, to develop a risk analysis of frequent flooding, the data product chosen should include precipitation at greater than a diurnal frequency and over multi-decadal timescales. This kind of product is most likely to be available using the dynamical downscaling method. SERDP reviewed the various advantages and disadvantages of using each type of downscaling method and downscaling dataset, and developed a recommended process that is publicly available<ref name="Kotamarthi2016"/>. In general, the following recommendations should be considered in order to pick the right downscaled dataset for a given analysis:

| + | ==Equilibrium Determination (Tracers)== |

| | + | The equilibration period of peepers can last several weeks and depends on deployment conditions, analyte of interest, and peeper design. In many cases, it is advantageous to use pre-equilibrium methods that can use measurements in peepers deployed for shorter periods to predict concentrations at equilibrium<ref name="USEPA2017">USEPA, 2017. Laboratory, Field, and Analytical Procedures for Using Passive Sampling in the Evaluation of Contaminated Sediments: User’s Manual. EPA/600/R-16/357. [[Media: EPA_600_R-16_357.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref>. |

| | | | |

| − | * When a problem depends on using a large number of climate models and emission scenarios to perform preliminary assessments and to understand the uncertainty range of projections, then using a statistical downscaled dataset is recommended.

| + | Although the equilibrium concentration of an analyte in sediment can be evaluated by examining analyte results for peepers deployed for several different amounts of time (i.e., a time series), this is impractical for typical field investigations because it would require several mobilizations to the site to retrieve samplers. Alternately, reverse tracers (referred to as a performance reference compound when used with organic compound passive sampling) can be used to evaluate the percentage of equilibrium reached by a passive sampler. |

| − | * When the assessment needs a more extensive parameter list or is analyzing a region with few long-term observational data, dynamically downscaled climate change projections are recommended.

| |

| | | | |

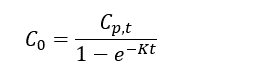

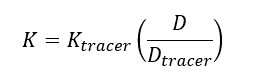

| − | ==Uncertainty in Projections==

| + | Thomas and Arthur<ref name="ThomasArthur2010"/> studied the use of a reverse tracer to estimate percent equilibrium in lab experiments and a field application. They concluded that bromide can be used to estimate concentrations in porewater using measurements obtained before equilibrium is reached. Further studies were also conducted by Risacher ''et al.''<ref name="RisacherEtAl2023"/> showed that lithium can also be used as a tracer for brackish and saline environments. Both studies included a mathematical model for estimating concentrations of ions in external media (''C<small><sub>0</sub></small>'') based on measured concentrations in the peeper chamber (''C<small><sub>p,t</sub></small>''), the elimination rate of the target analyte (''K'') and the deployment time (''t''): |

| − | {| class="wikitable" style="float:right; margin-left:10px;text-align:center;"

| + | </br> |

| − | |+Table 2. Downscaling Model Characteristics and Output<ref name="Kotamarthi2016"/>

| + | {| |

| | + | | || '''Equation 1:''' |

| | + | | [[File: Equation1r.png]] |

| | |- | | |- |

| − | !Model or</br>Dataset Name

| + | | Where: || || |

| − | !Model<br />Method

| |

| − | !Output<br />Variables

| |

| − | !Output<br />Format

| |

| − | !Spatial</br>Resolution

| |

| − | !Time</br>Resolution

| |

| | |- | | |- |

| − | | colspan="6" style="text-align: left; background-color:white;" |'''Statistical Downscaled Datasets''' | + | | || ''C<small><sub>0</sub></small>''|| is the freely dissolved concentration of the analyte in the sediment (mg/L or μg/L), sometimes referred to as ''C<small><sub>free</sub></small> |

| | |- | | |- |

| − | | [https://worldclim.org/data/index.html WorldClim]<ref name="Hijmans2005">Hijmans, R.J., Cameron, S.E., Parra, J.L., Jones, P.G. and Jarvis, A., 2005. Very High Resolution Interpolated Climate Surfaces for Global Land Areas. International Journal of Climatology: A Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 25(15), pp 1965-1978. [https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.1276 DOI: 10.1002/joc.1276]</ref> | + | | || ''C<small><sub>p,t</sub></small>'' || is the measured concentration of the analyte in the peeper at time of retrieval (mg/L or μg/L) |

| − | |Delta||T(min, max,</br>avg), Pr||NetCDF||grid: 30 arc sec to</br>10 arc min||month

| |

| | |- | | |- |

| − | | Bias Corrected / Spatial</br>Disaggregation (BCSD)<ref name="Wood2002">Wood, A.W., Maurer, E.P., Kumar, A. and Lettenmaier, D.P., 2002. Long‐range experimental hydrologic forecasting for the eastern United States. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 107(D20), 4429, pp. ACL6 1-15. [https://doi.org/10.1029/2001JD000659 DOI:10.1029/2001JD000659] Free access article available from: [https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1029/2001JD000659 American Geophysical Union] [[Media: Wood2002.pdf | Report.pdf ]]</ref> | + | | || ''K'' || is the elimination rate of the target analyte |

| − | |Empirical Quantile</br>Mapping||Runoff,</br>Streamflow||NetCDF||grid: 7.5 arc min||day | |

| | |- | | |- |

| − | | [https://cida.usgs.gov/thredds/catalog.html?dataset=dcp Asynchronous Regional Regression</br>Model (ARRM v.1)]<ref name="Stoner2013">Stoner, A.M., Hayhoe, K., Yang, X., and Wuebbles, D.J., 2013. An Asynchronous Regional Regression Model for Statistical Downscaling of Daily Climate Variables. International Journal of Climatology, 33(11), pp. 2473-2494. [https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.3603 DOI:10.1002/joc.3603]</ref> | + | | || ''t'' || is the deployment time (days) |

| − | |Parameterized</br>Quantile Mapping||T(min, max), Pr||NetCDF||stations plus</br>grid: 7.5 arc min||day | + | |} |

| − | |-

| + | |

| − | | [https://sdsm.org.uk/ Statistical Downscaling</br>Model (SDSM)]<ref name="Wilby2013">Wilby, R.L., and Dawson, C.W., 2013. The Statistical DownScaling Model: insights from one decade of application. International Journal of Climatology, 33(7), pp. 1707-1719. [https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.3544 DOI: 10.1002/joc.3544]</ref>

| + | The elimination rate of the target analyte (''K'') is calculated using Equation 2: |

| − | |Weather</br>Generator||T(min, max), Pr||PC Code||stations||day

| + | </br> |

| − | |- | + | {| |

| − | | [https://climate.northwestknowledge.net/MACA/ Multivariate Adaptive</br>Constructed Analogs</br>(MACA)]<ref name="Hidalgo2008">Hidalgo, H.G., Dettinger, M.D. and Cayan, D.R., 2008. Downscaling with Constructed Analogues: Daily Precipitation and Temperature Fields Over the United States. California Energy Commission PIER Final Project, Report CEC-500-2007-123. [[Media: Hidalgo2008.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref>

| + | | || '''Equation 2:''' |

| − | |Constructed Analogues||10 Variables||NetCDF||grid: 2.5 arc min||day

| + | | [[File: Equation2r.png]] |

| | |- | | |- |

| − | | [http://loca.ucsd.edu/ Localized Constructed</br>Analogs (LOCA)]<ref name="Pierce2013">Pierce, D.W., Cayan, D.R. and Thrasher, B.L., 2014. Statistical Downscaling Using Localized Constructed Analogs (LOCA). Journal of Hydrometeorology, 15(6), pp. 2558-2585. [https://doi.org/10.1175/JHM-D-14-0082.1 DOI: 10.1175/JHM-D-14-0082.1] Free access article available from: [https://journals.ametsoc.org/view/journals/hydr/15/6/jhm-d-14-0082_1.xml American Meteorological Society]. [[Media: Pierce2014.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref> | + | | Where: || || |

| − | |Constructed Analogues||T(min, max), Pr||NetCDF||grid: 3.75 arc min||day

| |

| | |- | | |- |

| − | | [https://www.nccs.nasa.gov/services/data-collections/land-based-products/nex-dcp30 NASA Earth Exchange</br>Downscaled Climate</br>Projections (NEX-DCP30)]<ref name="Wood2002"/> | + | | || ''K''|| is the elimination rate of the target analyte |

| − | |Bias Correction /</br>Spatial Disaggregation||T(min, max), Pr||NetCDF||grid: 30 arc sec||month | |

| | |- | | |- |

| − | | colspan="6" style="text-align: left; background-color:white;" |'''Dynamical Downscaled Datasets''' | + | | || ''K<small><sub>tracer</sub></small>'' || is the elimination rate of the tracer |

| | |- | | |- |

| − | | [http://www.narccap.ucar.edu/index.html North American Regional Climate</br>Change Assessment Program (NARCCAP)]<ref name="Mearns2009">Mearns, L.O., Gutowski, W., Jones, R., Leung, R., McGinnis, S., Nunes, A. and Qian, Y., 2009. A Regional Climate Change Assessment Program for North America. Eos, Transactions, American Geophysical Union, 90(36), p.311. [https://doi.org/10.1029/2009EO360002 DOI: 10.1029/2009EO360002] Free access article from: [https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1029/2009EO360002 American Geophysical Union] [[Media: Mearns2009.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref> | + | | || ''D'' || is the free water diffusivity of the analyte (cm<sup>2</sup>/s) |

| − | |Multiple Models||49 Variables||NetCDF||grid: 30 arc min||3 hours

| |

| | |- | | |- |

| − | | [https://cordex.org/about/ Coordinated Regional Climate</br>Downscaling Experiment (CORDEX)]<ref name="Giorgi2009">Giorgi, F., Jones, C., and Asrar, G.R., 2009. Addressing climate information needs at the regional level: the CORDEX framework. World Meteorological Organization (WMO) Bulletin, 58(3), pp. 175-183. Free access article from: [https://public.wmo.int/en/bulletin/addressing-climate-information-needs-regional-level-cordex-framework World Meteorological Organization] [[Media: Giorgi2009.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref> | + | | || ''D<small><sub>tracer</sub></small>'' || is the free water diffusivity of the tracer (cm<sup>2</sup>/s) |

| − | |Multiple Models||66 Variables||NetCDF||grid: 30 arc min||3 hours | |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | [https://esrl.noaa.gov/gsd/wrfportal/ Strategic Environmental Research and</br>Development Program (SERDP)]<ref name="Wang2015">Wang, J., and Kotamarthi, V.R., 2015. High‐resolution dynamically downscaled projections of precipitation in the mid and late 21st century over North America. Earth's Future, 3(7), pp. 268-288. [https://doi.org/10.1002/2015EF000304 DOI: 10.1002/2015EF000304] Free access article from: [https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/2015EF000304 American Geophysical Union] [[Media: Wang2015.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref>

| |

| − | |Weather Research and</br>Forecasting (WRF v3.3)||80+ Variables||NetCDF||grid: 6.5 arc min||3 hours

| |

| | |} | | |} |

| − | A primary cause of uncertainty in climate change projections, especially beyond 30 years into the future, is the uncertainty in the greenhouse gas (GHG) emission scenarios used to make climate model projections. The best method of accounting for this type of uncertainty is to apply a climate change model to multiple GHG emission scenarios (see also: [[Wikipedia: Representative Concentration Pathway]]).

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The uncertainties in climate projections over shorter timescales, less than 30 years out, are dominated by something known as “internal variability” in the models. Different approaches are used to address the uncertainty from internal variability<ref name="Kotamarthi2021"/>. A third type of uncertainty in climate modeling, known as scientific uncertainty, comes from our inability to numerically solve every aspect of the complex earth system. We expect this scientific uncertainty to decrease as we understand more of the earth system and improve its representation in our numerical models. As discussed in [[Climate Change Primer]], numerical experiments based on global climate models are designed to address these uncertainties in various ways. Downscaling methods evaluate this uncertainty by using several independent regional climate models to generate future projections, with the expectation that each of these models will capture some aspects of the physics better than the others, and that by using several different models, we can estimate the range of this uncertainty. Thus, the commonly accepted methods for accounting for uncertainty in climate model projections are either using projections from one model for several emission scenarios, or applying multiple models to project a single scenario.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | A comparison of the currently available methods and their characteristics is provided in Table 2 (adapted from Kotamarthi et al., 2016<ref name="Kotamarthi2016"/>). The table lists the various methodologies and models used for producing downscaled data, and the climate variables that these methods produce. These datasets are mostly available for download from the data servers and websites listed in the table and in a few cases by contacting the respective source organizations.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The most popular and widely used format for atmospheric and climate science is known as [[Wikipedia:NetCDF | NetCDF]], which stands for Network Common Data Form. NetCDF is a self-describing data format that saves data in a binary format. The format is self-describing in that a metadata listing is part of every file that describes all the data attributes, such as dimensions, units and data size and in principal should not need additional information to extract the required data for analysis with the right software. However, specially built software for reading and extracting data from these binary files is necessary for making visualizations and further analysis. Software packages for reading and writing NetCDF datasets and for generating visualizations from these datasets are widely available and obtained free of cost ([https://www.unidata.ucar.edu/software/netcdf/docs/ NetCDF-tools]). Popular geospatial analysis tools such as ARC-GIS, statistical packages such as ‘R’ and programming languages such as Fortran, C++, and Python have built in libraries that can be used to directly read NetCDF files for visualization and analysis.

| |

| − |

| |

| | | | |

| − | | + | The elimination rate of the tracer (''K<small><sub>tracer</sub></small>'') is calculated using Equation 3: |

| − | [[File: Gschwend1w2fig1.png | thumb | 300px | Figure 1. A representation of a clam living in a sediment bed that contains a chemical contaminant (depicted as red hexagons). The contaminant is partly dissolved in the sediment porewater between the solid grains, and partly associated with solid phases, like natural organic matter and "black carbons" such as soots from diesel engines and chars emitted during forest fires. All of these liquid and solid materials can exchange their contaminant loads with one another, with the distributions dependent on the chemical's relative affinity for each material. When an animal like the clam moves into this system, the chemical is also accumulated into the animal, until the animal is also equilibrated with the other solids and liquid(s) present.]]

| + | </br> |

| − | Environmental media such as sediments typically contain many different materials or phases, including liquid solutions (e.g. water, [[Light Non-Aqueous Phase Liquids (LNAPLs)| nonaqueous phase liquids]] like spilled oils) and diverse solids (e.g., quartz, aluminosilicate clays, and combustion-derived soots). Further, the chemical concentration in the porewater medium includes both molecules that are "truly dissolved" in the water and others that are associated with colloids in the porewater<ref name="Brownawell1986">Brownawell, B.J., and Farrington, J.W., 1986. Biogeochemistry of PCBs in interstitial waters of a coastal marine sediment. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 50(1), pp. 157-169. [https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7037(86)90061-X DOI: 10.1016/0016-7037(86)90061-X] Free download available from: [https://semspub.epa.gov/work/01/268631.pdf US EPA].</ref><ref name="Chin1992">Chin, Y.P., and Gschwend, P.M., 1992. Partitioning of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons to Marine Porewater Organic Colloids. Environmental Science and Technology, 26(8), pp. 1621-1626. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es00032a020 DOI: 10.1021/es00032a020]</ref><ref name="Achman1996">Achman, D.R., Brownawell, B.J., and Zhang, L., 1996. Exchange of Polychlorinated Biphenyls Between Sediment and Water in the Hudson River Estuary. Estuaries, 19(4), pp. 950-965. [https://doi.org/10.2307/1352310 DOI: 10.2307/1352310] Free download available from: [https://www.academia.edu/download/55010335/135231020171114-2212-b93vic.pdf Academia.edu]</ref>. As a result, contaminant chemicals distribute among these diverse media (Figure 1) according to their affinity for each and the amount of each phase in the system<ref name="Gustafsson1996">Gustafsson, Ö., Haghseta, F., Chan, C., MacFarlane, J., and Gschwend, P.M., 1996. Quantification of the Dilute Sedimentary Soot Phase: Implications for PAH Speciation and Bioavailability. Environmental Science and Technology, 31(1), pp. 203-209. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es960317s DOI: 10.1021/es960317s]</ref><ref name="Luthy1997">Luthy, R.G., Aiken, G.R., Brusseau, M.L., Cunningham, S.D., Gschwend, P.M., Pignatello, J.J., Reinhard, M., Traina, S.J., Weber, W.J., and Westall, J.C., 1997. Sequestration of Hydrophobic Organic Contaminants by Geosorbents. Environmental Science and Technology, 31(12), pp. 3341-3347. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es970512m DOI: 10.1021/es970512m]</ref><ref name="Lohmann2005">Lohmann, R., MacFarlane, J.K., and Gschwend, P.M., 2005. Importance of Black Carbon to Sorption of Native PAHs, PCBs, and PCDDs in Boston and New York Harbor Sediments. Environmental Science and Technology, 39(1), pp.141-148. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es049424+ DOI: 10.1021/es049424+]</ref><ref name="Cornelissen2005">Cornelissen, G., Gustafsson, Ö., Bucheli, T.D., Jonker, M.T., Koelmans, A.A., and van Noort, P.C., 2005. Extensive Sorption of Organic Compounds to Black Carbon, Coal, and Kerogen in Sediments and Soils: Mechanisms and Consequences for Distribution, Bioaccumulation, and Biodegradation. Environmental Science and Technology, 39(18), pp. 6881-6895. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es050191b DOI: 10.1021/es050191b]</ref><ref name="Koelmans2009">Koelmans, A.A., Kaag, K., Sneekes, A., and Peeters, E.T.H.M., 2009. Triple Domain in Situ Sorption Modeling of Organochlorine Pesticides, Polychlorobiphenyls, Polyaromatic Hydrocarbons, Polychlorinated Dibenzo-p-Dioxins, and Polychlorinated Dibenzofurans in Aquatic Sediments. Environmental Science and Technology, 43(23), pp. 8847-8853. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es9021188 DOI: 10.1021/es9021188]</ref>. As such, the chemical concentration in any one medium (e.g., truly dissolved in porewater) in a multi-material system like sediment is very hard to know from measures of the total sediment concentration, which unfortunately is the information typically found by analyzing for chemicals in sediment samples.

| + | {| |

| − | | + | | || '''Equation 3:''' |

| − | If an animal moves into this system, it will also accumulate the chemical in its tissues from the loads in all the other materials (Figure 1). This can lead to exposures of the chemical to other organisms, including humans, who may eat such animals. Predicting the quantity of contaminant in the animal requires knowledge of the relative affinities of the chemical for the animal versus the sediment materials. For example, if one knew the chemical's truly dissolved concentration in the porewater and could reasonably assume the chemical of interest in the animal has mostly accumulated in its lipids (as is often the case for very hydrophobic compounds), then one could estimate the chemical concentration in the animal (''C<sub><small>animal</small></sub>'', typically in units of μg/kg animal wet weight) using a lipid-water [[Wikipedia: Partition coefficient | partition coefficient]], ''K<sub><small>lipid-water</small></sub>'', typically in units of (μg/kg lipid)'''/'''(μg/L water), and the porewater concentration of the chemical (''C<sub><small>porewater</small></sub>'', in μg/L) with Equation 1.

| + | | [[File: Equation3r2.png]] |

| − | {|

| |

| − | |

| |

| | |- | | |- |

| − | | || Equation 1. | + | | Where: || || |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"| <big>'''''C<sub><small>animal</small></sub> '''=''' f<sub><small>lipid</small></sub> '''x''' K<sub><small>lipid-water</small></sub> '''x''' C<sub><small>porewater</small></sub>'''''</big> | |

| | |- | | |- |

| − | | where: | + | | || ''K<small><sub>tracer</sub></small>'' || is the elimination rate of the tracer |

| | |- | | |- |

| − | | || ''f<sub><small>lipid</small></sub>'' || is the fraction lipids contribute to the total wet weight of the animal (kg lipid/kg animal wet weight), and | + | | || ''C<small><sub>tracer,i</sub></small>''|| is the measured initial concentration of the tracer in the peeper prior to deployment (mg/L or μg/L) |

| | |- | | |- |

| − | | || ''C<sub><small>porewater</small></sub>'' || is the freely dissolved contaminant concentration in the porewater surrounding the animal. | + | | || ''C<small><sub>tracer,t</sub></small>'' || is the measured final concentration of the tracer in the peeper at time of retrieval (mg/L or μg/L) |

| − | |}

| |

| − | | |

| − | While there is a great deal of information on the values of ''K<sub><small>lipid-water</small></sub>'' for many chemicals<ref name="Schwarzenbach2017">Schwarzenbach, R.P., Gschwend, P.M., and Imboden, D.M., 2017. Environmental Organic Chemistry, 3rd edition. Ch. 16: Equilibrium Partitioning from Water and Air to Biota, pp. 469-521. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN: 978-1-118-76723-8</ref>, it is often very inaccurate to estimate truly dissolved porewater concentrations from total sediment concentrations using assumptions about the affinity of those chemicals for the solids in the system<ref name="Gustafsson1996"/>. Further, it is difficult to isolate porewater without colloids and/or measure the very low truly dissolved concentrations of hydrophobic contaminants of concern like [[Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) | polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs)]], [[Wikipedia: Polychlorinated biphenyl | polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs)]], nonionic pesticides like [[Wikipedia: DDT | dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT)]], and [[Wikipedia: Polychlorinated dibenzodioxins | polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins (PCDDs)]]/[[Wikipedia: Polychlorinated dibenzofurans | dibenzofurans (PCDFs)]]<ref name="Hawthorne2005">Hawthorne, S.B., Grabanski, C.B., Miller, D.J., and Kreitinger, J.P., 2005. Solid-Phase Microextraction Measurement of Parent and Alkyl Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Milliliter Sediment Pore Water Samples and Determination of K<sub><small>DOC</small></sub> Values. Environmental Science and Technology, 39(8), pp. 2795-2803. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es0405171 DOI: 10.1021/es0405171]</ref>.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==Passive Samplers==

| |

| − | One approach to address this problem for contaminated sediments is to insert into the sediment billets of organic polymers like low density polyethylene (LDPE), polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), or polyoxymethylene (POM) that can absorb such hydrophobic chemicals from their surroundings<ref name="Mayer2000">Mayer, P., Vaes, W.H., Wijnker, F., Legierse, K.C., Kraaij, R., Tolls, J., and Hermens, J.L., 2000. Sensing Dissolved Sediment Porewater Concentrations of Persistent and Bioaccumulative Pollutants Using Disposable Solid-Phase Microextraction Fibers. Environmental Science and Technology, 34(24), pp. 5177-5183. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es001179g DOI: 10.1021/es001179g]</ref><ref name="Booij2003">Booij, K., Hoedemaker, J.R., and Bakker, J.F., 2003. Dissolved PCBs, PAHs, and HCB in Pore Waters and Overlying Waters of Contaminated Harbor Sediments. Environmental Science and Technology, 37(18), pp. 4213-4220. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es034147c DOI: 10.1021/es034147c]</ref><ref name="Cornelissen2008">Cornelissen, G., Pettersen, A., Broman, D., Mayer, P., and Breedveld, G.D., 2008. Field testing of equilibrium passive samplers to determine freely dissolved native polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon concentrations. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 27(3), pp. 499-508. [https://doi.org/10.1897/07-253.1 DOI: 10.1897/07-253.1]</ref><ref name="Tomaszewski2008">Tomaszewski, J.E., and Luthy, R.G., 2008. Field Deployment of Polyethylene Devices to Measure PCB Concentrations in Pore Water of Contaminated Sediment. Environmental Science and Technology, 42(16), pp. 6086-6091. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es800582a DOI: 10.1021/es800582a]</ref><ref name="Fernandez2009">Fernandez, L.A., MacFarlane, J.K., Tcaciuc, A.P., and Gschwend, P.M., 2009. Measurement of Freely Dissolved PAH Concentrations in Sediment Beds Using Passive Sampling with Low-Density Polyethylene Strips. Environmental Science and Technology, 43(5), pp. 1430-1436. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es802288w DOI: 10.1021/es802288w]</ref><ref name="Arp2015">Arp, H.P.H., Hale, S.E., Elmquist Kruså, M., Cornelissen, G., Grabanski, C.B., Miller, D.J., and Hawthorne, S.B., 2015. Review of polyoxymethylene passive sampling methods for quantifying freely dissolved porewater concentrations of hydrophobic organic contaminants. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 34(4), pp. 710-720. [https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.2864 DOI: 10.1002/etc.2864] [https://setac.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/etc.2864 Free access article.] [[Media: Arp2015.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref><ref name="Apell2016"/>. In this approach, the polymer is inserted in the sediment bed where it absorbs some of the contaminant load via the contaminant's diffusion into the polymer from the surroundings. When the polymer achieves sorptive equilibration with the sediments, the chemical concentration in the polymer, ''C<sub><small>polymer</small></sub>'' (μg/kg polymer), can be used to find the corresponding concentration in the porewater, ''C<sub><small>porewater</small></sub>'' (μg/L), using a polymer-water partition coefficient, ''K<sub><small>polymer-water</small></sub>'' ((μg/kg polymer)'''/'''(μg/L water)), that has previously been found in laboratory testing<ref name="Lohmann2012">Lohmann, R., 2012. Critical Review of Low-Density Polyethylene’s Partitioning and Diffusion Coefficients for Trace Organic Contaminants and Implications for Its Use as a Passive Sampler. Environmental Science and Technology, 46(2), pp. 606-618. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es202702y DOI: 10.1021/es202702y]</ref><ref name="Ghosh2014">Ghosh, U., Kane Driscoll, S., Burgess, R.M., Jonker, M.T., Reible, D., Gobas, F., Choi, Y., Apitz, S.E., Maruya, K.A., Gala, W.R., Mortimer, M., and Beegan, C., 2014. Passive Sampling Methods for Contaminated Sediments: Practical Guidance for Selection, Calibration, and Implementation. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management, 10(2), pp. 210-223. [https://doi.org/10.1002/ieam.1507 DOI: 10.1002/ieam.1507] [https://setac.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/ieam.1507 Free access article.] [[Media: Ghosh2014.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref>, as shown in Equation 2.

| |

| − | {|

| |

| − | |

| |

| | |- | | |- |

| − | | || Equation 2. | + | | || ''t'' || is the deployment time (days) |

| − | | style="width:600px; text-align:center;" | <big>'''''C<sub><small>porewater</small></sub> '''=''' C<sub><small>polymer</small></sub> '''/''' K<sub><small>polymer-water</small></sub>'''''</big>

| |

| − | |} | |

| − | | |

| − | Such “passive uptake” by the polymer also reflects the availability of the chemicals for transport to adjacent systems (e.g., overlying surface waters) and for uptake into organisms (e.g., [[Wikipedia: Bioaccumulation | bioaccumulation]]). Thus, one can use the porewater concentrations to estimate the biotic accumulation of the chemicals, too. For example, for the concentration in the animal equilibrated with the sediment, ''C<sub><small>animal</small></sub>'' (μg/kg animal), would be found by combining Equations 1 and 2 to get Equation 3.

| |

| − | {|

| |

| − | |

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | || Equation 3.

| |

| − | |style="width:700px; text-align:center;" |<big>'''''C<sub><small>animal</small></sub> '''=''' f<sub><small>lipid</small></sub> '''x''' K<sub><small>lipid-water</small></sub> '''x''' C<sub><small>polymer</small></sub> '''/''' K<sub><small>polymer-water</small></sub>'''''</big>

| |

| | |} | | |} |

| − | [[File: Gschwend1w2fig2a.PNG | thumb | 300px | Figure 2a. Plot of the initial concentrations of a PRC (green lines) in a polyethylene (PE) sheet inserted in a sediment showing constant concentration across the PE and zero concentration outside the PE. At the same time, a target contaminant of interest (red lines) initially has a constant concentration in the sediment outside the PE and zero concentration inside the PE.]][[File: Gschwend1w2fig2b.PNG | thumb | 300px | Figure 2b. After the PE has been deployed for a time, the PRC is depleted from the PE (green lines), especially near the surfaces contacting the sediment, and its concentration is building up outside the PE and diffusing away into the sediment. Meanwhile, the target chemical leaves the sediment and begins to diffuse into the PE (red lines). The "jumps" in concentration at the PE-sediment boundary reflect the equilibrium paritioning coefficient,</br>''K<sub>PE-sed</sub> = C<sub>PE</sub> / C<sub>sediment</sub>''.]]

| |

| | | | |

| − | ==Performance Reference Compounds (PRCs)==

| + | Using this set of equations allows the calculation of the porewater concentration of the analyte prior to its equilibrium with the peeper water. A template for these calculations can be found in the appendix of Risacher ''et al.''<ref name="RisacherEtAl2023"/>. |

| − | Perhaps unsurprisingly, pollutants with low water solubility like PAHs, PCBs, etc. do not diffuse quickly through sediment beds. As a result, their accumulation in polymeric materials in sediments can take a long time to achieve equilibration<ref name="Fernandez2009b">Fernandez, L. A., Harvey, C.F., and Gschwend, P.M., 2009. Using Performance Reference Compounds in Polyethylene Passive Samplers to Deduce Sediment Porewater Concentrations for Numerous Target Chemicals. Environmental Science and Technology, 43(23), pp. 8888-8894. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es901877a DOI: 10.1021/es901877a]</ref><ref name="Lampert2015">Lampert, D.J., Thomas, C., and Reible, D.D., 2015. Internal and external transport significance for predicting contaminant uptake rates in passive samplers. Chemosphere, 119, pp. 910-916. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.08.063 DOI: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.08.063] Free download available from: [https://www.academia.edu/download/44146586/chemosphere_2014.pdf Academia.edu]</ref><ref name="Apell2016b">Apell, J.N., Tcaciuc, A.P., and Gschwend, P.M., 2016. Understanding the rates of nonpolar organic chemical accumulation into passive samplers deployed in the environment: Guidance for passive sampler deployments. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management, 12(3), pp. 486-492. [https://doi.org/10.1002/ieam.1697 DOI: 10.1002/ieam.1697]</ref>. This problem was recognized previously for passive samplers called [[Wikipedia: Semipermeable membrane devices | semipermeable membrane devices]] (SPMDs, e.g. polyethylene bags filled with triolein<ref name="Huckins2002">Huckins, J.N., Petty, J.D., Lebo, J.A., Almeida, F.V., Booij, K., Alvarez, D.A., Cranor, W.L., Clark, R.C., and Mogensen, B.B., 2002. Development of the Permeability/Performance Reference Compound Approach for In Situ Calibration of Semipermeable Membrane Devices. Environmental Science and Technology, 36(1), pp. 85-91. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es010991w DOI: 10.1021/es010991w]</ref>) that were deployed in surface waters. As a result, representative chemicals called performance reference compound (PRCs) were dosed inside the samplers before their deployment in the environment, and the PRCs' diffusive losses out of the SPMD could be used to quantify the fractional approach toward sampler-environmental surroundings equilibration<ref name="Booij2002">Booij, K., Smedes, F., and van Weerlee, E.M., 2002. Spiking of performance reference compounds in low density polyethylene and silicone passive water samplers. Chemosphere 46(8), pp.1157-1161. [https://doi.org/10.1016/S0045-6535(01)00200-4 DOI: 10.1016/S0045-6535(01)00200-4]</ref><ref name="Huckins2002"/>. A similar approach can be used for polymers inserted in sediment beds<ref name="Fernandez2009b"/><ref name="Apell2014"/>. Commonly, isotopically labeled forms of the compounds of interest such as deuterated or <sup>13</sup>C-labelled PAHs or PCBs are homogeneously impregnated into the polymers before their deployments. Upon insertion of the polymer into the sediment bed (or overlying waters or even air), the initially evenly distributed PRCs begin to diffuse out of the sampling polymer and into the surroundings (Figure 2).

| |

| | | | |

| − | Assuming the contaminants of interest undergo the same mass transfer restrictions limiting their rates of uptake into the polymer (e.g., diffusion through the sedimentary porous medium) that are also limiting transfers of the PRCs out of the polymer<ref name="Fernandez2009b"/><ref name="Apell2014"/>, then fractional losses of the PRCs during a particular deployment can be used to adjust the accumulated contaminant loads to what they would have been at equilibrium with their surroundings with Equation 4.

| + | ==Using Peeper Data at a Sediment Site== |

| − | {|

| + | Peeper data can be used to enable site specific decision making in a variety of ways. Some of the most common uses for peepers and peeper data are discussed below. |

| − | |

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | || Equation 4.

| |

| − | | style="text-align:center;"| <big>'''''C(<sub>∞</sub>)<sub><small>polymer</small></sub> '''=''' C(<small>t</small>)<sub><small>polymer</small></sub> '''/''' f<sub><small>PRC lost</small></sub>'''''</big>

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | where:

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | || ''f<sub><small>PRC lost</small></sub>'' || is the fraction of the PRC lost to outward diffusion,

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | || ''C(<sub>∞</sub>)<sub><small>polymer</small></sub>'' || is the concentration of the contaminant in the polymer at equilibrium, and

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | || ''C(<small>t</small>)<sub><small>polymer</small></sub>'' || is the concentration of the contaminant in the polymer after deployment time, t.

| |

| − | |}

| |

| | | | |

| − | Since investigators are commonly interested in many chemicals at the same time, it is impractical to have a PRC for each contaminant of interest. Instead, a representative set of PRCs is used to characterize the rates of polymer-environment exchange as a function of the PRCs' properties (e.g., diffusivities, partition coefficients), the sediments characteristics (e.g., porosity), and the nature of the polymer used (e.g., film thickness, affinity for the chemicals)<ref name="Fernandez2009b"/><ref name="Lampert2015"/>. The resulting mass transfer model fit can then be used to estimate the fractional approaches to equilibrium for many other contaminants, whose diffusive and partitioning properties are also known. And these fractions can be used to adjust the target chemical concentrations that have accumulated from the sediment into the same polymeric sampler to find the equilibrated results<ref name="Apell2014"/>. Finally, these equilibrated concentrations can be used in Eq. 2 to estimate truly dissolved contaminant concentrations in the sediment's porewater.

| + | '''Nature and Extent:''' Multiple peepers deployed in sediment can help delineate areas of increased metal availability. Peepers are especially helpful for sites that are comprised of coarse, relatively inert materials that may not be conducive to traditional bulk sediment sampling. Because much of the inorganics present in these types of sediments may be associated with the porewater phase rather than the solid phase, peepers can provide a more representative measurement of C<small><sub>0</sub></small>. Additionally, at sites where tidal pumping or groundwater flux may be influencing the nature and extent of inorganics, peepers can provide a distinct advantage to bulk sediment sampling or other point-in-time measurements, as peepers can provide an average measurement that integrates the variability in the hydrodynamic and chemical conditions over time. |

| | | | |

| − | ==Field Applications==

| + | '''Sources and Fate:''' A considerable advantage to using peepers is that C<small><sub>0</sub></small> results are expressed as concentration in units of mass per volume (e.g., mg/L), providing a common unit of measurement to compare across multiple media. For example, synchronous measurements of C<small><sub>0</sub></small> using peepers deployed in both surface water and sediment can elucidate the potential flux of inorganics from sediment to surface water. Paired measurements of both C<small><sub>0</sub></small> and bulk metals in sediment can also allow site specific sediment-porewater partition coefficients to be calculated. These values can be useful in understanding and predicting contaminant fate, especially in situations where the potential dissolution of metals from sediment are critical to predict, such as when sediment is dredged. |

| − | [[File: Gschwend1w2fig3.png | thumb |left| 450px | Figure 3. Passive sampler system made of polyethylene sheet loaded into an aluminum sheet metal frame, before (left), during (middle), and after (right) deployment in sediment.]]

| |

| − | Polymeric materials can be deployed in sediment in various ways<ref name="Burgess2017"/>. PDMS coatings can be incorporated into slotted silica rods called SPMEs (solid phase micro extraction devices), while thin sheets of polymers like LDPE or POM can be incorporated into sheet metal frames. In both cases, such hardware is used to insert the polymers into sediment beds (Figure 3).

| |

| | | | |

| − | Deployment of the assembled passive samplers can be accomplished via poles from a boat<ref name="Apell2014"/>, by divers<ref name="Apell2016"/>, or by attaching the samplers to a sampling platform lowered off a vessel<ref name="Fernandez2012">Fernandez, L.A., Lao, W., Maruya, K.A., White, C., Burgess, R.M., 2012. Passive Sampling to Measure Baseline Dissolved Persistent Organic Pollutant Concentrations in the Water Column of the Palos Verdes Shelf Superfund Site. Environmental Science and Technology, 46(21), pp. 11937-11947. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es302139y DOI: 10.1021/es302139y]</ref>. Typically, the method used depends on the water depth. Small buoys on short lines, sometimes with associated water-sampling polymeric materials in mesh bags (see right panel of Figure 3), are attached to the samplers to facilitate the sampler recoveries. After recovery, the samplers are wiped to remove any adhering sediment, biofilm, or precipitates and returned to the laboratory for PRC and target contaminant analyses. The resulting measurements of the accumulated target chemical concentrations can be adjusted using the observed PRC losses and publicly available software programs<ref name="Gschwend2014">Gschwend, P.M., Tcaciuc, A.P., and Apell, J.N., 2014. Guidance Document: Passive PE Sampling in Support of In Situ Remediation of Contaminated Sediments – Passive Sampler PRC Calculation Software User’s Guide, US Department of Defense, Environmental Security Technology Certification Program Project ER-200915. Available from: [https://www.serdp-estcp.org/Program-Areas/Environmental-Restoration/Contaminated-Sediments/Bioavailability/ER-200915 ESTCP].</ref><ref name="Thompson2015">Thompson, J.M., Hsieh, C.H. and Luthy, R.G., 2015. Modeling Uptake of Hydrophobic Organic Contaminants into Polyethylene Passive Samplers. Environmental Science and Technology, 49(4), pp. 2270-2277. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es504442s DOI: 10.1021/es504442s]</ref>.

| + | '''Direct Toxicity to Aquatic Life:''' Peepers are frequently used to understand the potential direct toxicity to aquatic life, such as benthic invertebrates and fish. A C<small><sub>0</sub></small> measurement obtained from a peeper deployed in sediment (''in situ'') or surface water (''ex situ''), can be compared to toxicological benchmarks for aquatic life to understand the potential toxicity to aquatic life and to set remediation goals<ref name="USEPA2017"/>. C<small><sub>0</sub></small> measurements can also be incorporated in more sophisticated approaches, such as the Biotic Ligand Model<ref>Santore, C.R., Toll, E.J., DeForest, K.D., Croteau, K., Baldwin, A., Bergquist, B., McPeek, K., Tobiason, K., and Judd, L.N., 2022. Refining our understanding of metal bioavailability in sediments using information from porewater: Application of a multi-metal BLM as an extension of the Equilibrium Partitioning Sediment Benchmarks. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management, 18(5), pp. 1335–1347. [https://doi.org/10.1002/ieam.4572 doi: 10.1002/ieam.4572]</ref> to understand the potential for toxicity or the need to conduct toxicological testing or ecological evaluations. |

| | | | |

| − | Subsequently, since the passive sampling reveals the concentrations of contaminants in a sediment bed's porewater and the overlying bottom water<ref name="Booij2003"/>, the data can be used to estimate bed-to-water column diffusive fluxes of contaminants<ref name="Koelmans2010">Koelmans, A.A., Poot, A., De Lange, H.J., Velzeboer, I., Harmsen, J., and van Noort, P.C.M., 2010. Estimation of In Situ Sediment-to-Water Fluxes of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons, Polychlorobiphenyls and Polybrominated Diphenylethers. Environmental Science and Technology, 44(8), pp. 3014-3020. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es903938z DOI: 10.1021/es903938z]</ref><ref name="Fernandez2012"/> and bioirrigation-affected fluxes<ref name="Apell2018">Apell, J.N., Shull, D.H., Hoyt, A.M., and Gschwend, P.M., 2018. Investigating the Effect of Bioirrigation on In Situ Porewater Concentrations and Fluxes of Polychlorinated Biphenyls Using Passive Samplers. Environmental Science and Technology, 52(8), pp. 4565-4573. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.7b05809 DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.7b05809]</ref>. The data are also useful for assessing the tendency of the contaminants to accumulate in benthic organisms<ref name="Vinturella2004">Vinturella, A.E., Burgess, R.M., Coull, B.A., Thompson, K.M., and Shine, J.P., 2004. Use of Passive Samplers to Mimic Uptake of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons by Benthic Polychaetes. Environmental Science and Technology, 38(4), pp. 1154-1160. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es034706f DOI: 10.1021/es034706f]</ref><ref name="Yates2011">Yates, K., Pollard, P., Davies, I.M., Webster, L., and Moffat, C.F., 2011. Application of silicone rubber passive samplers to investigate the bioaccumulation of PAHs by Nereis virens from marine sediments. Environmental Pollution, 159(12), pp. 3351-3356. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2011.08.038 DOI: 10.1016/j.envpol.2011.08.038]</ref><ref name="Fernandez2015">Fernandez, L.A. and Gschwend, P.M., 2015. Predicting bioaccumulation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in soft-shelled clams (Mya arenaria) using field deployments of polyethylene passive samplers. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 34(5), pp. 993-1000. [https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.2892 DOI: 10.1002/etc.2892]</ref>, and by extension into food webs that include such benthic species<ref name="vonStackelberg2017">von Stackelberg, K., Williams, M.A., Clough, J., and Johnson, M.S., 2017. Spatially explicit bioaccumulation modeling in aquatic environments: Results from 2 demonstration sites. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management, 13(6), pp. 1023-1037. [https://doi.org/10.1002/ieam.1927 DOI: 10.1002/ieam.1927]</ref>. Furthermore, recent efforts have found that passive sampling observations can be used to infer ''in situ'' transformations of substances like nitro aromatic compounds<ref name="Belles2016">Belles, A., Alary, C., Criquet, J., and Billon, G., 2016. A new application of passive samplers as indicators of in-situ biodegradation processes. Chemosphere, 164, pp. 347-354. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.08.111 DOI: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.08.111]</ref> and DDT<ref name="Tcaciuc2018">Tcaciuc, A.P., Borrelli, R., Zaninetta, L.M., and Gschwend, P.M., 2018. Passive sampling of DDT, DDE and DDD in sediments: accounting for degradation processes with reaction–diffusion modeling. Environmental Science: Processes and Impacts, 20(1), pp. 220-231. [https://doi.org/10.1039/C7EM00501F DOI: 10.1039/C7EM00501F] Open access article available from: [https://pubs.rsc.org/--/content/articlehtml/2018/em/c7em00501f Royal Society of Chemistry].</ref>.

| + | '''Bioaccumulation of Inorganics by Aquatic Life:''' Peepers can also be used to understand site specific relationship between C<small><sub>0</sub></small> and concentrations of inorganics in aquatic life. For example, measuring C<small><sub>0</sub></small> in sediment from which organisms are collected and analyzed can enable the estimation of a site-specific uptake factor. This C<small><sub>0</sub></small>-to-organism uptake factor (or model) can then be applied for a variety of uses, including predicting the concentration of inorganics in other organisms, or estimating a sediment C<small><sub>0</sub></small> value that would be safe for consumption by wildlife or humans. Because several decades of research have found that the correlation between C<small><sub>0</sub></small> measurements and bioavailability is usually better than the correlation between measurements of chemicals in bulk sediment and bioavailability, C<small><sub>0</sub></small>-to-organism uptake factors are likely to be more accurate than uptake factors based on bulk sediment testing. |

| | | | |

| − | <br clear="left" /> | + | '''Evaluating Sediment Remediation Efficacy:''' Passive sampling has been used widely to evaluate the efficacy of remedial actions such as active amendments, thin layer placements, and capping to reduce the availability of contaminants at sediment sites. A particularly powerful approach is to compare baseline (pre-remedy) C<small><sub>0</sub></small> in sediment to C<small><sub>0</sub></small> in sediment after the sediment remedy has been applied. Peepers can be used in this context for inorganics, allowing the sediment remedy’s success to be evaluated and monitored in laboratory benchtop remedy evaluations, pilot scale remedy evaluations, and full-scale remediation monitoring. |

| | | | |

| | ==References== | | ==References== |

| | <references /> | | <references /> |

| | + | |

| | ==See Also== | | ==See Also== |

| − | | + | *[https://vimeo.com/809180171/c276c1873a Peeper Deployment Video] |

| − | [https://www.serdp-estcp.org/Tools-and-Training/Tools/PRC-Correction-Calculator A PRC Correction Calculator for LDPE deployed in sediments] | + | *[https://vimeo.com/811073634/303edf2693 Peeper Retrieval Video] |

| | + | *[https://vimeo.com/811328715/aea3073540 Peeper Processing Video] |

| | + | *[https://sepub-prod-0001-124733793621-us-gov-west-1.s3.us-gov-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2024-09/ER20-5261%20Fact%20Sheet.pdf?VersionId=malAixSQQM3mWCRiaVaxY8wLdI0jE1PX Fact Sheet] |

Sediment Porewater Dialysis Passive Samplers for Inorganics (Peepers)

Sediment porewater dialysis passive samplers, also known as “peepers,” are sampling devices that allow the measurement of dissolved inorganic ions in the porewater of a saturated sediment. Peepers function by allowing freely-dissolved ions in sediment porewater to diffuse across a micro-porous membrane towards water contained in an isolated compartment that has been inserted into sediment. Once retrieved after a deployment period, the resulting sample obtained can provide concentrations of freely-dissolved inorganic constituents in sediment, which provides measurements that can be used for understanding contaminant fate and risk. Peepers can also be used in the same manner in surface water, although this article is focused on the use of peepers in sediment.

Related Article(s):

Contributor(s):

- Florent Risacher, M.Sc.

- Jason Conder, Ph.D.

Key Resource(s):

- A review of peeper passive sampling approaches to measure the availability of inorganics in sediment porewater[1]

- Best Practices User’s Guide: Standardizing Sediment Porewater Passive Samplers for Inorganic Constituents of Concern[2]

Introduction

Biologically available inorganic constituents associated with sediment toxicity can be quantified by measuring the freely-dissolved fraction of contaminants in the porewater[3][4]. Classical sediment porewater analysis usually consists of collecting large volumes of bulk sediments which are then mechanically squeezed or centrifuged to produce a supernatant, or suction of porewater from intact sediment, followed by filtration and collection[5]. The extraction and measurement processes present challenges due to the heterogeneity of sediments, physical disturbance, high reactivity of some complexes, and interaction between the solid and dissolved phases, which can impact the measured concentration of dissolved inorganics[6]. For example, sampling disturbance can affect redox conditions[7][8], which can lead to under or over representation of inorganic chemical concentrations relative to the true dissolved phase concentration in the sediment porewater[9][5].

To address the complications with mechanical porewater sampling, passive sampling approaches for inorganics have been developed to provide a method that has a low impact on the surrounding geochemistry of sediments and sediment porewater, thus enabling more precise measurements of inorganics[4]. Sediment porewater dialysis passive samplers, also known as “peepers,” were developed more than 45 years ago[10] and refinements to the method such as the use of reverse tracers have been made, improving the acceptance of the technology as decision making tool.

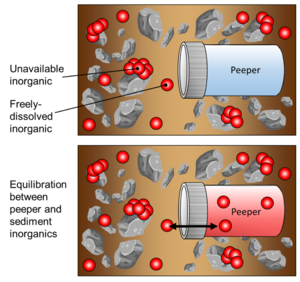

Peeper Designs

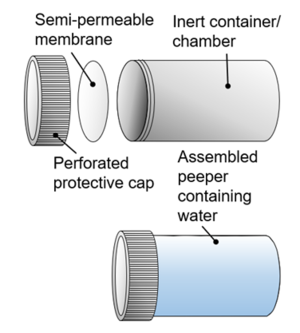

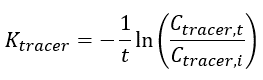

Figure 1. Conceptual illustration of peeper construction showing (top, left to right) the peeper cap (optional), peeper membrane and peeper chamber, and (bottom) an assembled peeper containing peeper water

Figure 2. Example of Hesslein

[10] general peeper design (42 peeper chambers), from

USGS

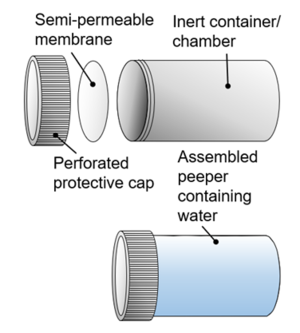

Figure 3. Peeper deployment structure to allow the measurement of metal availability in different sediment layers using five single-chamber peepers (Photo: Geosyntec Consultants)

Peepers (Figure 1) are inert containers with a small volume (typically 1-100 mL) of purified water (“peeper water”) capped with a semi-permeable membrane. Peepers can be manufactured in a wide variety of formats (Figure 2, Figure 3) and deployed in in various ways.

Two designs are commonly used for peepers. Frequently, the designs are close adaptations of the original multi-chamber Hesslein design[10] (Figure 2), which consists of an acrylic sampler body with multiple sample chambers machined into it. Peeper water inside the chambers is separated from the outside environment by a semi-permeable membrane, which is held in place by a top plate fixed to the sampler body using bolts or screws. An alternative design consists of single-chamber peepers constructed using a single sample vial with a membrane secured over the mouth of the vial, as shown in Figure 3, and applied in Teasdale et al.[7], Serbst et al.[11], Thomas and Arthur[12], Passeport et al.[13], and Risacher et al.[2]. The vial is filled with deionized water, and the membrane is held in place using the vial cap or an o-ring. Individual vials are either directly inserted into sediment or are incorporated into a support structure to allow multiple single-chamber peepers to be deployed at once over a given depth profile (Figure 3).

Peepers Preparation, Deployment and Retrieval

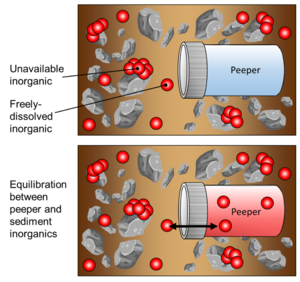

Figure 4: Conceptual illustration of peeper passive sampling in a sediment matrix, showing peeper immediately after deployment (top) and after equilibration between the porewater and peeper chamber water (bottom)

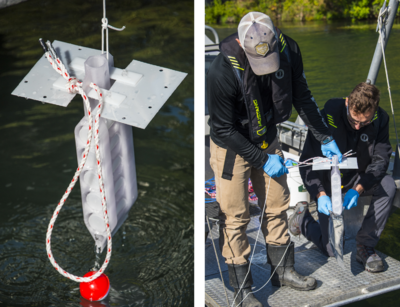

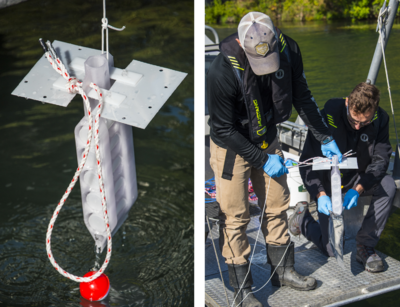

Peepers are often prepared in laboratories but are also commercially available in a variety of designs from several suppliers. Peepers are prepared by first cleaning all materials to remove even trace levels of metals before assembly. The water contained inside the peeper is sometimes deoxygenated, and in some cases the peeper is maintained in a deoxygenated atmosphere until deployment[14]. However, recent studies[2] have shown that deoxygenation prior to deployment does not significantly impact sampling results due to oxygen rapidly diffusing out of the peeper during deployment. Once assembled, peepers are usually shipped in a protective bag inside a hard-case cooler for protection.

Peepers are deployed by insertion into sediment for a period of a few days to a few weeks. Insertion into the sediment can be achieved by wading to the location when the water depth is shallow, by using push poles for deeper deployments[2], or by professional divers for the deepest sites. If divers are used, an appropriate boat or ship will be required to accommodate the diver and their equipment. Whichever method is used, peepers should be attached to an anchor or a small buoy to facilitate retrieval at the end of the deployment period.

During deployment, passive sampling is achieved via diffusion of inorganics through the peeper’s semi-permeable membrane, as the enclosed volume of peeper water equilibrates with the surrounding sediment porewater (Figure 4). It is assumed that the peeper insertion does not greatly alter geochemical conditions that affect freely-dissolved inorganics. Additionally, it is assumed that the peeper water equilibrates with freely-dissolved inorganics in sediment in such a way that the concentration of inorganics in the peeper water would be equal to that of the concentration of inorganics in the sediment porewater.

After retrieval, the peepers are brought to the surface and usually preserved until they can be processed. This can be achieved by storing the peepers inside a sealable, airtight bag with either inert gas or oxygen absorbing packets[2]. The peeper water can then be processed by quickly pipetting it into an appropriate sample bottle which usually contains a preservative (e.g., nitric acid for metals). This step is generally conducted in the field. Samples are stored on ice to maintain a temperature of less than 4°C and shipped to an analytical laboratory. The samples are then analyzed for inorganics by standard methods (i.e., USEPA SW-846). The results obtained from the analytical laboratory are then used directly or assessed using the equations below if a reverse tracer is used because deployment time is insufficient for all analytes to reach equilibrium.

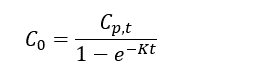

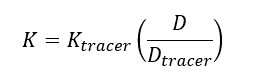

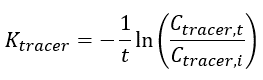

Equilibrium Determination (Tracers)

The equilibration period of peepers can last several weeks and depends on deployment conditions, analyte of interest, and peeper design. In many cases, it is advantageous to use pre-equilibrium methods that can use measurements in peepers deployed for shorter periods to predict concentrations at equilibrium[15].