Difference between revisions of "PFAS Treatment by Anion Exchange"

(→Costs and the Importance of Treatment Criteria) |

(→Costs and the Importance of Treatment Criteria) |

||

| Line 54: | Line 54: | ||

<onlyinclude>Life cycle cost analyses show that anion exchange treatment is a viable alternative to GAC adsorption</onlyinclude><ref name="LiuEtAl2022" /><ref name="EllisEtAl2023" />. Like other adsorption treatment systems, single-use AER treatment systems have fairly simple design with lead-lag reactor vessels in series together with associated pumping, plumbing and any water pretreatment processes (e.g., sediment filters, process for metals removal). While similar in design to GAC treatment systems, single-use AER treatment systems can have significantly lower capital costs due to the smaller reaction vessels used (as a result of shorter required EBCTs for AER)<ref name="EllisEtAl2023" />. The smaller reactor sizes may also reduce associated costs for any structure required to house the reactors. Capital costs for regenerable AER systems are more difficult to estimate because of their added system complexity, including added infrastructure for resin regeneration, cosolvent recovery by distillation, and still bottoms management. Over the full life cycle of AER treatment systems, typically >10 years, operating costs are expected to dominate overall PFAS treatment costs<ref name="EllisEtAl2023" />. These costs are determined largely by media usage rate (MUR), which is the frequency for replacement and disposal or regeneration of exhausted resins. Despite the higher unit costs of anion exchange media relative to GAC (often ≥3-fold greater per m<sup>3</sup>), the superior adsorption capacity and PFAS affinity of AERs leads to lower MURs that more than offset this increased sorbent cost<onlyinclude>. </onlyinclude> | <onlyinclude>Life cycle cost analyses show that anion exchange treatment is a viable alternative to GAC adsorption</onlyinclude><ref name="LiuEtAl2022" /><ref name="EllisEtAl2023" />. Like other adsorption treatment systems, single-use AER treatment systems have fairly simple design with lead-lag reactor vessels in series together with associated pumping, plumbing and any water pretreatment processes (e.g., sediment filters, process for metals removal). While similar in design to GAC treatment systems, single-use AER treatment systems can have significantly lower capital costs due to the smaller reaction vessels used (as a result of shorter required EBCTs for AER)<ref name="EllisEtAl2023" />. The smaller reactor sizes may also reduce associated costs for any structure required to house the reactors. Capital costs for regenerable AER systems are more difficult to estimate because of their added system complexity, including added infrastructure for resin regeneration, cosolvent recovery by distillation, and still bottoms management. Over the full life cycle of AER treatment systems, typically >10 years, operating costs are expected to dominate overall PFAS treatment costs<ref name="EllisEtAl2023" />. These costs are determined largely by media usage rate (MUR), which is the frequency for replacement and disposal or regeneration of exhausted resins. Despite the higher unit costs of anion exchange media relative to GAC (often ≥3-fold greater per m<sup>3</sup>), the superior adsorption capacity and PFAS affinity of AERs leads to lower MURs that more than offset this increased sorbent cost<onlyinclude>. </onlyinclude> | ||

| − | <onlyinclude>A critical parameter that will dictate media usage or regeneration, and ultimately O&M costs, is the criteria used to determine when ‘PFAS breakthrough’ is reached. Sites are typically contaminated with a mix of different PFAS that will breakthrough resin beds into effluent at different bed volumes of water. For example, short-chain PFCAs breakthrough much more rapidly than long-chain PFCAs and PFSAs, so selection of treatment criteria that include short-chain PFCAs like perfluorobutanoic acid (PFBA) will necessitate more frequent media replacement or regeneration than criteria focused on long-chain PFAS. | + | <onlyinclude>A critical parameter that will dictate media usage or regeneration, and ultimately O&M costs, is the criteria used to determine when ‘PFAS breakthrough’ is reached. </onlyinclude>Sites are typically contaminated with a mix of different PFAS that will breakthrough resin beds into effluent at different bed volumes of water. For example, short-chain PFCAs breakthrough much more rapidly than long-chain PFCAs and PFSAs, so selection of treatment criteria that include short-chain PFCAs like perfluorobutanoic acid (PFBA) will necessitate more frequent media replacement or regeneration than criteria focused on long-chain PFAS. Likewise, adoption of the proposed drinking water limits for PFOS and PFOA (4 ng/L each)<ref>USEPA, 2023. PFAS National Primary Drinking Water Regulation Rulemaking. 88 Federal Register, pp. 18638-18754. [https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/03/29/2023-05471/pfas-national-primary-drinking-water-regulation-rulemaking Federal Register Website]</ref> in effluent of the lead vessel of a lead-lag reactor system as the breakthrough criteria will require more frequent media replacement than using a less stringent criteria (e.g., 50% breakthrough of either compound in the lead vessel). Breakthrough criteria can also affect media selection because the performance advantages of the more expensive PFAS-selective AER over regenerable AER and GAC are most apparent when media replacement/regeneration is dictated by breakthrough of long-chain PFCAs and PFSAs, and when a greater extent of media adsorption capacity is used before replacement/regeneration; these advantages shrink when media replacement/regeneration is dictated by breakthrough of short-chain PFCAs<ref name="EllisEtAl2023" /><ref name="EllisEtAl2022" /><ref name="ChowEtAl2022" />. While purchase of new media and disposal of exhausted media are minimal with regenerable AER, costs are still linked closely to regeneration frequency because of the needs for consumables (salt brine, cosolvent) and management and disposal of the resulting waste regenerant solutions, which often far exceeds media waste in terms of total waste mass and volume. These costs may be reduced by recovering cosolvent and destruction of PFAS in the resulting still bottoms<ref name="BoyerEtAl2021b" />, areas of active research and development<ref name="StrathmannEtAl2020" /><ref name="HuangEtAl2021" /> |

==References== | ==References== | ||

Revision as of 15:08, 11 September 2024

Anion exchange has emerged as one of the most effective and economical technologies for treatment of water contaminated by per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Anion exchange resins (AERs) are polymer beads (0.5–1 mm diameter) incorporating cationic adsorption sites that attract anionic PFAS by a combination of electrostatic and hydrophobic mechanisms. Both regenerable and single-use resin treatment systems are being investigated, and results from pilot-scale studies show that AERs can treat much greater volumes of PFAS-contaminated water than comparable amounts of granular activated carbon (GAC) adsorbent media. Life cycle treatment costs and environmental impacts of anion exchange and other adsorbent technologies are highly dependent upon the treatment criteria selected by site managers to determine when media is exhausted and requires replacement or regeneration.

Related Article(s):

- Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)

- PFAS Sources

- PFAS Transport and Fate

- PFAS Ex Situ Water Treatment

- Supercritical Water Oxidation (SCWO)

- PFAS Treatment by Electrical Discharge Plasma

Contributor(s): Dr. Timothy J. Strathmann, Dr. Anderson Ellis and Dr. Treavor H. Boyer

Key Resource(s):

- Anion Exchange Resin Removal of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) from Impacted Water: A Critical Review[1]

- Regenerable Resin Sorbent Technologies with Regenerant Solution Recycling for Sustainable Treatment of PFAS; SERDP Project ER18-1063 Final Report[2]

Introduction

Anion exchange is an adsorptive treatment technology that uses polymeric resin beads (0.5–1 mm diameter) that incorporate cationic adsorption sites to remove anionic pollutants from water[4]. Anions (e.g., NO3-) are adsorbed by an ion exchange reaction with anions that are initially bound to the adsorption sites (e.g., Cl-) during resin preparation. Many per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) of concern, including perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS), are present in contaminated water as anionic species that can be adsorbed by anion exchange reactions[1][5][6].

Resins most commonly utilized for PFAS treatment are strong base anion exchange resins (SB-AERs) that incorporate quaternary ammonium cationic functional groups with hydrocarbon side chains (R-groups) that promote PFAS adsorption by a combination of electrostatic and hydrophobic mechanisms (Figure 1)[1][7]. SB-AERs maintain cationic functional groups independent of water pH. Recently introduced ‘PFAS-selective’ AERs show >1,000,000-fold greater selectivity for some PFAS over the Cl- initially loaded onto resins[8]. These resins also show much higher adsorption capacities for PFAS (mg PFAS adsorbed per gram of adsorbent media) than granular activated carbon (GAC) adsorbents.

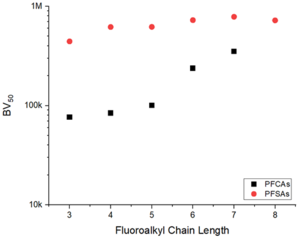

PFAS of concern have a wide range of structures, including perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids (PFCAs) and perfluoroalkyl sulfonic acids (PFSAs) of varying carbon chain length[9]. As such, affinity for adsorption to AERs is heavily dependent upon PFAS structure[1][5]. In general, it has been found that the extent of adsorption increases with increasing chain length, and that PFSAs adsorb more strongly than PFCAs of similar chain length (Figure 2)[8][10]. The chain length-dependence supports the conclusion that PFAS-resin hydrophobic mechanisms contribute to adsorption. Adsorption of polyfluorinated structures also depends on structure and prevailing charge, with adsorption of zwitterionic species (containing both anionic and cationic groups in the same structure) to AERs being documented despite having a net neutral charge[8].

Reactors for Treatment of PFAS-Contaminated Water

Anion exchange treatment of water is accomplished by pumping contaminated water through fixed bed reactors filled with AERs (Figure 3). A common configuration involves flowing water through two reactors arranged in a lead-lag configuration[11]. Water flows through the pore spaces in close contact with resin beads. Sufficient contact time needs to be provided, referred to as empty bed contact time (EBCT), to allow PFAS to diffuse from the water into the resin structure and adsorb to exchange sites. Typical EBCTs for AER treatment of PFAS are 2-5 min, shorter than contact times recommended for granular activated carbon (GAC) adsorbents (≥10 min)[12][13]. The higher adsorption capacities and shorter EBCTs of AERs enable use of much less media and smaller vessels than GAC, reducing expected capital costs for AER treatment systems[14].

Like other adsorption media, PFAS will initially adsorb to media encountered near the inlet side of the reactor, but as ion exchange sites become saturated with PFAS, the active zone of adsorption will begin to migrate through the packed bed with increasing volume of water treated. Moreover, some PFAS with lower affinity for exchange sites (e.g., shorter-chain PFAS that are less hydrophobic) will be displaced by competition from other PFAS (e.g., longer-chain PFAS that are more hydrophobic) and move further along the bed to occupy open sites[15]. Eventually, PFAS will start to breakthrough into the effluent from the reactor, typically beginning with the shorter-chain compounds. The initial breakthrough of shorter-chain PFAS is similar to the behavior observed for AER treatment of inorganic contaminants.

Upon breakthrough, treatment is halted, and the exhausted resins are either replaced with fresh media or regenerated before continuing treatment. Most vendors are currently operating AER treatment systems for PFAS in single-use mode where virgin media is delivered to replace exhausted resins, which are transported off-site for disposal or incineration[1]. As an alternative, some providers are developing regenerable AER treatment systems, where exhausted resins are regenerated on-site by desorbing PFAS from the resins using a combination of salt brine (typically ≥1 wt% NaCl) and cosolvent (typically ≥70 vol% methanol)[1][16][17]. This mode of operation allows for longer term use of resins before replacement, but requires more complex and extensive site infrastructure. Cosolvent in the resulting waste regenerant can be recycled by distillation, which reduces chemical inputs and lowers the volume of PFAS-contaminated still bottoms requiring further treatment or disposal[16]. Currently, there is active research on various technologies for destruction of PFAS concentrates in AER still bottoms residuals[3][18].

Field Demonstrations

Field pilot studies are critical to demonstrating the effectiveness and expected costs of PFAS treatment technologies. A growing number of pilot studies testing the performance of commercially available AERs to treat PFAS-contaminated groundwater, including sites impacted by historical use of aqueous film-forming foam (AFFF), have been published recently (Figure 4)[11][12][15][19][20]. A 9-month pilot study treating contaminated groundwater near an AFFF source zone, with total PFAS concentrations >20 μg/L, showed that single-use PFAS-selective resins significantly outperform more traditional regenerable resins[15]. No detectable concentrations of ≥C7 PFCAs or PFSAs of any length were observed in the first 150,000 bed volumes (BVs) of water treated with PFAS-selective resins provided by three different manufacturers (one BV is a volume of water equivalent to the volume occupied by the pore spaces in the reactor). Earlier breakthrough of shorter-chain PFCAs was observed for all resins, with the shortest chain structures eluting chromatographically (PFAS breakthrough order follows increasing chain length). Moreover, the superiority of PFAS-selective resins was less dramatic for shorter-chain PFCAs, highlighting the importance of site-specific treatment criteria when selecting among resins. Analysis of the used resin beds following completion of the study shows that breakthrough of PFAS with the lowest affinity for AERs (e.g., short-chain PFCAs) is accelerated by competitive displacement from adsorption sites by PFAS with greater affinity (e.g., PFSAs and long-chain PFCAs).

Another study treating a more dilute plume of AFFF-impacted groundwater (100 – 200 ng/L total PFAS) compared PFAS-selective AER with GAC[12]. The same compound-dependent breakthrough patterns were observed with all media, where earlier PFCA breakthrough will likely dictate media changeout requirements. Comparing AER with GAC shows that the former adsorbed 6-7 times more PFAS than the latter before breakthrough. All PFSAs appear to breakthrough AER simultaneously after >100,000 BVs due to fouling of resins by metals present in the sourcewater, highlighting the potential importance of sourcewater pretreatment. Although AERs outperform GAC, estimated operation and maintenance (O&M) costs for both media are similar due to the higher unit media costs for AER.

A third pilot study compared the long-term (>1 year) performance of PFAS-selective AERs with GAC treating contaminated groundwater dominated by short-chain PFCAs[19]. As noted in other studies, AER outperform GAC on a bed volume-normalized basis, especially for longer-chain PFCAs and PFSAs. With lower site groundwater concentrations, quantitative relationships between chain length and breakthrough was observed for both PFCAs and PFSAs, with log-linear relationships being observed between BV10 and BV50 (bed volumes at which 10% and 50% breakthrough occurs, respectively) and chain length. These investigators also noted that deviations from a linear PFAS structure (e.g., branching of the perfluoroalkyl chain) negatively affects AER adsorption to a lesser extent than GAC.

While most pilot studies have focused on evaluating single-use AERs, pilot studies have also been undertaken to test anion exchange treatment systems employing regenerable AER[11]. Operating lead-lag packed beds, with 5-min EBCT each, the regenerable AER delayed breakthrough of PFCAs and PFSAs compared to GAC. Effluent PFOA breakthrough from the lag bed of AER occurred after ~10,000 BVs, necessitating resin regeneration, which was accomplished by backflushing with 10 BVs of a salt brine/organic cosolvent mixture (+1 BV salt brine pre-rinse and 10 BVs potable water post-rinse). PFAS removal results using the regenerated resin were then found to be comparable with virgin resin. Preliminary tests showed that cosolvent use can be minimized by recovering from the waste regenerant mixture by distillation. A number of studies are currently underway to test the effectiveness of different technologies for destruction of PFAS concentrates in the resulting still bottoms residual.

Costs and the Importance of Treatment Criteria

Life cycle cost analyses show that anion exchange treatment is a viable alternative to GAC adsorption[12][14]. Like other adsorption treatment systems, single-use AER treatment systems have fairly simple design with lead-lag reactor vessels in series together with associated pumping, plumbing and any water pretreatment processes (e.g., sediment filters, process for metals removal). While similar in design to GAC treatment systems, single-use AER treatment systems can have significantly lower capital costs due to the smaller reaction vessels used (as a result of shorter required EBCTs for AER)[14]. The smaller reactor sizes may also reduce associated costs for any structure required to house the reactors. Capital costs for regenerable AER systems are more difficult to estimate because of their added system complexity, including added infrastructure for resin regeneration, cosolvent recovery by distillation, and still bottoms management. Over the full life cycle of AER treatment systems, typically >10 years, operating costs are expected to dominate overall PFAS treatment costs[14]. These costs are determined largely by media usage rate (MUR), which is the frequency for replacement and disposal or regeneration of exhausted resins. Despite the higher unit costs of anion exchange media relative to GAC (often ≥3-fold greater per m3), the superior adsorption capacity and PFAS affinity of AERs leads to lower MURs that more than offset this increased sorbent cost.

A critical parameter that will dictate media usage or regeneration, and ultimately O&M costs, is the criteria used to determine when ‘PFAS breakthrough’ is reached. Sites are typically contaminated with a mix of different PFAS that will breakthrough resin beds into effluent at different bed volumes of water. For example, short-chain PFCAs breakthrough much more rapidly than long-chain PFCAs and PFSAs, so selection of treatment criteria that include short-chain PFCAs like perfluorobutanoic acid (PFBA) will necessitate more frequent media replacement or regeneration than criteria focused on long-chain PFAS. Likewise, adoption of the proposed drinking water limits for PFOS and PFOA (4 ng/L each)[21] in effluent of the lead vessel of a lead-lag reactor system as the breakthrough criteria will require more frequent media replacement than using a less stringent criteria (e.g., 50% breakthrough of either compound in the lead vessel). Breakthrough criteria can also affect media selection because the performance advantages of the more expensive PFAS-selective AER over regenerable AER and GAC are most apparent when media replacement/regeneration is dictated by breakthrough of long-chain PFCAs and PFSAs, and when a greater extent of media adsorption capacity is used before replacement/regeneration; these advantages shrink when media replacement/regeneration is dictated by breakthrough of short-chain PFCAs[14][15][19]. While purchase of new media and disposal of exhausted media are minimal with regenerable AER, costs are still linked closely to regeneration frequency because of the needs for consumables (salt brine, cosolvent) and management and disposal of the resulting waste regenerant solutions, which often far exceeds media waste in terms of total waste mass and volume. These costs may be reduced by recovering cosolvent and destruction of PFAS in the resulting still bottoms[16], areas of active research and development[3][18]

References

- ^ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Boyer, T.H., Fang, Y., Ellis, A., Dietz, R., Choi, Y.J., Schaefer, C.E., Higgins, C.P., Strathmann, T.J., 2021. Anion Exchange Resin Removal of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) from Impacted Water: A Critical Review. Water Research, 200, Article 117244. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2021.117244 Open Access Manuscript.pdf

- ^ Strathmann, T.J., Higgins, C.P., Boyer, T., Schaefer, C., Ellis, A., Fang, Y., del Moral, L., Dietz, R., Kassar, C., Graham, C, 2023. Regenerable Resin Sorbent Technologies with Regenerant Solution Recycling for Sustainable Treatment of PFAS; SERDP Project ER18-1063 Final Report. 285 pages. Project Website Report.pdf

- ^ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Strathmann, T.J., Higgins, C., Deeb, R., 2020. Hydrothermal Technologies for On-Site Destruction of Site Investigation Wastes Impacted by PFAS, Final Report - Phase I. SERDP Project ER18-1501. Project Website Report.pdf

- ^ SenGupta, A.K., 2017. Ion Exchange in Environmental Processes: Fundamentals, Applications and Sustainable Technology. Wiley. ISBN:9781119157397 Wiley Online Library

- ^ 5.0 5.1 Dixit, F., Dutta, R., Barbeau, B., Berube, P., Mohseni, M., 2021. PFAS Removal by Ion Exchange Resins: A Review. Chemosphere, 272, Article 129777. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.129777

- ^ Rahman, M.F., Peldszus, S., Anderson, W.B., 2014. Behaviour and Fate of Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) in Drinking Water Treatment: A Review. Water Research, 50, pp. 318–340. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2013.10.045

- ^ Fuller, Mark. Ex Situ Treatment of PFAS-Impacted Groundwater Using Ion Exchange with Regeneration; ER18-1027. Project Website.

- ^ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Fang, Y., Ellis, A., Choi, Y.J., Boyer, T.H., Higgins, C.P., Schaefer, C.E., Strathmann, T.J., 2021. Removal of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) in Aqueous Film-Forming Foam (AFFF) Using Ion-Exchange and Nonionic Resins. Environmental Science and Technology, 55(8), pp. 5001–5011. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.1c00769

- ^ Interstate Technology Regulatory Council (ITRC), 2023. Technical Resources for Addressing Environmental Releases of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS). ITRC PFAS Website

- ^ Gagliano, E., Sgroi, M., Falciglia, P.P., Vagliasindi, F.G.A., Roccaro, P., 2020. Removal of Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) from Water by Adsorption: Role of PFAS Chain Length, Effect of Organic Matter and Challenges in Adsorbent Regeneration. Water Research, 171, Article 115381. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2019.115381

- ^ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Woodard, S., Berry, J., Newman, B., 2017. Ion Exchange Resin for PFAS Removal and Pilot Test Comparison to GAC. Remediation, 27(3), pp. 19–27. doi: 10.1002/rem.21515

- ^ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Liu, C. J., Murray, C.C., Marshall, R.E., Strathmann, T.J., Bellona, C., 2022. Removal of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances from Contaminated Groundwater by Granular Activated Carbon and Anion Exchange Resins: A Pilot-Scale Comparative Assessment. Environmental Science: Water Research and Technology, 8(10), pp. 2245–2253. doi: 10.1039/D2EW00080F

- ^ Liu, C.J., Werner, D., Bellona, C., 2019. Removal of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) from Contaminated Groundwater Using Granular Activated Carbon: A Pilot-Scale Study with Breakthrough Modeling. Environmental Science: Water Research and Technology, 5(11), pp. 1844–1853. doi: 10.1039/C9EW00349E

- ^ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 Ellis, A.C., Boyer, T.H., Fang, Y., Liu, C.J., Strathmann, T.J., 2023. Life Cycle Assessment and Life Cycle Cost Analysis of Anion Exchange and Granular Activated Carbon Systems for Remediation of Groundwater Contaminated by Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs). Water Research, 243, Article 120324. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2023.120324

- ^ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Ellis, A.C., Liu, C.J., Fang, Y., Boyer, T.H., Schaefer, C.E., Higgins, C.P., Strathmann, T.J., 2022. Pilot Study Comparison of Regenerable and Emerging Single-Use Anion Exchange Resins for Treatment of Groundwater Contaminated by per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs). Water Research, 223, Article 119019. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2022.119019 Open Access Manuscript

- ^ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Boyer, T.H., Ellis, A., Fang, Y., Schaefer, C.E., Higgins, C.P., Strathmann, T.J., 2021. Life Cycle Environmental Impacts of Regeneration Options for Anion Exchange Resin Remediation of PFAS Impacted Water. Water Research, 207, Article 117798. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2021.117798 Open Access Manuscript

- ^ Houtz, E., (projected completion 2025). Treatment of PFAS in Groundwater with Regenerable Anion Exchange Resin as a Bridge to PFAS Destruction, Project ER23-8391. Project Website.

- ^ 18.0 18.1 Huang, Q., Woodard, S., Nickleson, M., Chiang, D., Liang, S., Mora, R., 2021. Electrochemical Oxidation of Perfluoroalkyl Acids in Still Bottoms from Regeneration of Ion Exchange Resins Phase I - Final Report. SERDP Project ER18-1320. Project Website Report.pdf

- ^ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Chow, S.J., Croll, H.C., Ojeda, N., Klamerus, J., Capelle, R., Oppenheimer, J., Jacangelo, J.G., Schwab, K.J., Prasse, C., 2022. Comparative Investigation of PFAS Adsorption onto Activated Carbon and Anion Exchange Resins during Long-Term Operation of a Pilot Treatment Plant. Water Research, 226, Article 119198. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2022.119198

- ^ Zaggia, A., Conte, L., Falletti, L., Fant, M., Chiorboli, A., 2016. Use of Strong Anion Exchange Resins for the Removal of Perfluoroalkylated Substances from Contaminated Drinking Water in Batch and Continuous Pilot Plants. Water Research, 91, pp. 137–146. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2015.12.039

- ^ USEPA, 2023. PFAS National Primary Drinking Water Regulation Rulemaking. 88 Federal Register, pp. 18638-18754. Federal Register Website