Difference between revisions of "User:Jhurley/sandbox"

(→Peeper Designs) |

|||

| (748 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | == | + | ==Sediment Porewater Dialysis Passive Samplers for Inorganics (Peepers)== |

| − | + | Sediment porewater dialysis passive samplers, also known as “peepers,” are sampling devices that allow the measurement of dissolved inorganic ions in the porewater of a saturated sediment. Peepers function by allowing freely-dissolved ions in sediment porewater to diffuse across a micro-porous membrane towards water contained in an isolated compartment that has been inserted into sediment. Once retrieved after a deployment period, the resulting sample obtained can provide concentrations of freely-dissolved inorganic constituents in sediment, which provides measurements that can be used for understanding contaminant fate and risk. Peepers can also be used in the same manner in surface water, although this article is focused on the use of peepers in sediment. | |

| + | |||

<div style="float:right;margin:0 0 2em 2em;">__TOC__</div> | <div style="float:right;margin:0 0 2em 2em;">__TOC__</div> | ||

'''Related Article(s):''' | '''Related Article(s):''' | ||

| − | * [[ | + | *[[Contaminated Sediments - Introduction]] |

| − | * [[ | + | *[[Contaminated Sediment Risk Assessment]] |

| − | * [[ | + | *[[In Situ Treatment of Contaminated Sediments with Activated Carbon]] |

| + | *[[Passive Sampling of Munitions Constituents]] | ||

| + | *[[Sediment Capping]] | ||

| + | *[[Mercury in Sediments]] | ||

| + | *[[Passive Sampling of Sediments]] | ||

| − | '''Contributor(s):''' | + | |

| + | '''Contributor(s):''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Florent Risacher, M.Sc. | ||

| + | *Jason Conder, Ph.D. | ||

'''Key Resource(s):''' | '''Key Resource(s):''' | ||

| − | * | + | *A review of peeper passive sampling approaches to measure the availability of inorganics in sediment porewater<ref>Risacher, F.F., Schneider, H., Drygiannaki, I., Conder, J., Pautler, B.G., and Jackson, A.W., 2023. A Review of Peeper Passive Sampling Approaches to Measure the Availability of Inorganics in Sediment Porewater. Environmental Pollution, 328, Article 121581. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2023.121581 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2023.121581] [[Media: RisacherEtAl2023a.pdf | Open Access Manuscript]]</ref> |

| − | * | + | *Best Practices User’s Guide: Standardizing Sediment Porewater Passive Samplers for Inorganic Constituents of Concern<ref name="RisacherEtAl2023">Risacher, F.F., Nichols, E., Schneider, H., Lawrence, M., Conder, J., Sweett, A., Pautler, B.G., Jackson, W.A., Rosen, G., 2023b. Best Practices User’s Guide: Standardizing Sediment Porewater Passive Samplers for Inorganic Constituents of Concern, ESTCP ER20-5261. [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/db871313-fbc0-4432-b536-40c64af3627f Project Website] [[Media: ER20-5261BPUG.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref> |

| + | |||

| + | *[https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/db871313-fbc0-4432-b536-40c64af3627f/er20-5261-project-overview Standardizing Sediment Porewater Passive Samplers for Inorganic Constituents of Concern, ESTCP Project ER20-5261] | ||

==Introduction== | ==Introduction== | ||

| − | + | Biologically available inorganic constituents associated with sediment toxicity can be quantified by measuring the freely-dissolved fraction of contaminants in the porewater<ref>Conder, J.M., Fuchsman, P.C., Grover, M.M., Magar, V.S., Henning, M.H., 2015. Critical review of mercury SQVs for the protection of benthic invertebrates. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 34(1), pp. 6-21. [https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.2769 doi: 10.1002/etc.2769] [[Media: ConderEtAl2015.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref><ref name="ClevelandEtAl2017">Cleveland, D., Brumbaugh, W.G., MacDonald, D.D., 2017. A comparison of four porewater sampling methods for metal mixtures and dissolved organic carbon and the implications for sediment toxicity evaluations. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 36(11), pp. 2906-2915. [https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.3884 doi: 10.1002/etc.3884]</ref>. Classical sediment porewater analysis usually consists of collecting large volumes of bulk sediments which are then mechanically squeezed or centrifuged to produce a supernatant, or suction of porewater from intact sediment, followed by filtration and collection<ref name="GruzalskiEtAl2016">Gruzalski, J.G., Markwiese, J.T., Carriker, N.E., Rogers, W.J., Vitale, R.J., Thal, D.I., 2016. Pore Water Collection, Analysis and Evolution: The Need for Standardization. In: Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, Vol. 237, pp. 37–51. Springer. [https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-23573-8_2 doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-23573-8_2]</ref>. The extraction and measurement processes present challenges due to the heterogeneity of sediments, physical disturbance, high reactivity of some complexes, and interaction between the solid and dissolved phases, which can impact the measured concentration of dissolved inorganics<ref>Peijnenburg, W.J.G.M., Teasdale, P.R., Reible, D., Mondon, J., Bennett, W.W., Campbell, P.G.C., 2014. Passive Sampling Methods for Contaminated Sediments: State of the Science for Metals. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management, 10(2), pp. 179–196. [https://doi.org/10.1002/ieam.1502 doi: 10.1002/ieam.1502] [[Media: PeijnenburgEtAl2014.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref>. For example, sampling disturbance can affect redox conditions<ref name="TeasdaleEtAl1995">Teasdale, P.R., Batley, G.E., Apte, S.C., Webster, I.T., 1995. Pore water sampling with sediment peepers. Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 14(6), pp. 250–256. [https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-9936(95)91617-2 doi: 10.1016/0165-9936(95)91617-2]</ref><ref>Schroeder, H., Duester, L., Fabricius, A.L., Ecker, D., Breitung, V., Ternes, T.A., 2020. Sediment water (interface) mobility of metal(loid)s and nutrients under undisturbed conditions and during resuspension. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 394, Article 122543. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122543 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122543] [[Media: SchroederEtAl2020.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref>, which can lead to under or over representation of inorganic chemical concentrations relative to the true dissolved phase concentration in the sediment porewater<ref>Wise, D.E., 2009. Sampling techniques for sediment pore water in evaluation of reactive capping efficacy. Master of Science Thesis. University of New Hampshire Scholars’ Repository. 178 pages. [https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis/502 Website] [[Media: Wise2009.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref><ref name="GruzalskiEtAl2016"/>. | |

| + | |||

| + | To address the complications with mechanical porewater sampling, passive sampling approaches for inorganics have been developed to provide a method that has a low impact on the surrounding geochemistry of sediments and sediment porewater, thus enabling more precise measurements of inorganics<ref name="ClevelandEtAl2017"/>. Sediment porewater dialysis passive samplers, also known as “peepers,” were developed more than 45 years ago<ref name="Hesslein1976">Hesslein, R.H., 1976. An in situ sampler for close interval pore water studies. Limnology and Oceanography, 21(6), pp. 912-914. [https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.1976.21.6.0912 doi: 10.4319/lo.1976.21.6.0912] [[Media: Hesslein1976.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref> and refinements to the method such as the use of reverse tracers have been made, improving the acceptance of the technology as decision-making tool. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Peeper Designs== | ||

| + | Peepers (Figure 1) are inert containers with a small volume (typically 1-100 mL) of purified water (“peeper water”) capped with a semi-permeable membrane. Peepers can be manufactured in a wide variety of formats (Figure 2, Figure 3) and deployed in in various ways. | ||

| + | Two designs are commonly used for peepers. Frequently, the designs are close adaptations of the original multi-chamber Hesslein design<ref name="Hesslein1976"/> (Figure 2), which consists of an acrylic sampler body with multiple sample chambers machined into it. Peeper water inside the chambers is separated from the outside environment by a semi-permeable membrane, which is held in place by a top plate fixed to the sampler body using bolts or screws. An alternative design consists of single-chamber peepers constructed using a single sample vial with a membrane secured over the mouth of the vial, as shown in Figure 3, and applied in Teasdale ''et al.''<ref name="TeasdaleEtAl1995"/>, Serbst ''et al.''<ref>Serbst, J.R., Burgess, R.M., Kuhn, A., Edwards, P.A., Cantwell, M.G., Pelletier, M.C., Berry, W.J., 2003. Precision of dialysis (peeper) sampling of cadmium in marine sediment interstitial water. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 45(3), pp. 297–305. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s00244-003-0114-5 doi: 10.1007/s00244-003-0114-5]</ref>, Thomas and Arthur<ref name="ThomasArthur2010">Thomas, B., Arthur, M.A., 2010. Correcting porewater concentration measurements from peepers: Application of a reverse tracer. Limnology and Oceanography: Methods, 8(8), pp. 403–413. [https://doi.org/10.4319/lom.2010.8.403 doi: 10.4319/lom.2010.8.403] [[Media: ThomasArthur2010.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref>, Passeport ''et al.''<ref>Passeport, E., Landis, R., Lacrampe-Couloume, G., Lutz, E.J., Erin Mack, E., West, K., Morgan, S., Lollar, B.S., 2016. Sediment Monitored Natural Recovery Evidenced by Compound Specific Isotope Analysis and High-Resolution Pore Water Sampling. Environmental Science and Technology, 50(22), pp. 12197–12204. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b02961 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b02961]</ref>, and Risacher ''et al.''<ref name="RisacherEtAl2023"/>. The vial is filled with deionized water, and the membrane is held in place using the vial cap or an o-ring. Individual vials are either directly inserted into sediment or are incorporated into a support structure to allow multiple single-chamber peepers to be deployed at once over a given depth profile (Figure 3). | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | {| class="wikitable mw-collapsible" style="float:left; margin-right:20px; text-align:center;" | |

| − | + | |+Table 1. Analyte list with acronyms and CAS numbers. | |

| + | |- | ||

| + | !Compound | ||

| + | ! Acronym | ||

| + | !CAS Number | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1,2-Dinitrobenzene (surrogate) ||'''1,2-DNB (surr.)''' || 528-29-0 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1,3-Dinitrobenzene || 1,3-DNB || 99-65-0 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1,3,5-Trinitrobenzene || 1,3,5-TNB || 99-35-4 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1,4-Dinitrobenzene || '''1,4-DNB (surr.)''' || 100-25-4 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2-Amino-4,6-dinitrotoluene || 2-Am-4,6-DNT || 35572-78-2 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2-Nitrophenol || '''2-NP''' || 88-75-5 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2-Nitrotoluene || 2-NT || 88-72-2 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2,4-Dinitrophenol || '''2,4-DNP''' || 51-28-5 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2,4-Dinitrotoluene || 2,4-DNT || 121-14-2 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2,4,6-Trinitrophenol || '''Picric Acid (PA)''' || 88-89-1 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2,4,6-Trinitrotoluene || 2,4,6-TNT || 118-96-7 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2,6-Dinitrotoluene || 2,6-DNT || 606-20-2 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 3-Nitrotoluene || 3-NT || 99-08-1 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 3,5-Dinitroaniline || 3,5-DNA || 618-87-1 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 4-Amino-2,6-dinitrotoluene || 4-Am-2,6-DNT || 19406-51-0 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 4-Nitrophenol || '''4-NP''' || 100-02-7 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 4-Nitrotoluene || 4-NT || 99-99-0 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2,4-Dinitroanisole || '''DNAN''' || 119-27-7 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | Octahydro-1,3,5,7-tetranitro-1,3,5,7-tetrazocine || HMX || 2691-41-0 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | Nitrobenzene || NB || 98-95-3 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | Nitroglycerine || NG || 55-63-0 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | Nitroguanidine || '''NQ''' || 556-88-7 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 3-Nitro-1,2,4-triazol-5-one || '''NTO''' || 932-64-9 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | ''ortho''-Nitrobenzoic acid || '''''o''-NBA (surr.)''' || 552-16-9 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | Pentaerythritol tetranitrate || PETN || 78-11-5 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | Hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine || RDX || 121-82-4 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | N-Methyl-N-(2,4,6-trinitrophenyl)nitramide || Tetryl || 479-45-8 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | colspan="3" style="background-color:white;" | Note: Analytes in '''bold''' are not identified by EPA Method 8330B. | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | [[File: ScircleFig1.png | thumb | 400px | Figure 1. Primary Method labeled chromatograms]] | ||

| + | [[File: ScircleFig2.png | thumb | 400px | Figure 2. Secondary Method labeled chromatograms]] | ||

| + | The primary intention of the analytical methods presented here is to support the monitoring of legacy and insensitive munitions contamination on test and training ranges, however legacy and insensitive munitions often accompany each other at demilitarization facilities, manufacturing facilities, and other environmental sites. Energetic materials typically appear on ranges as small, solid particulates and due to their varying functional groups and polarities, can partition in various environmental compartments<ref>Walsh, M.R., Temple, T., Bigl, M.F., Tshabalala, S.F., Mai, N. and Ladyman, M., 2017. Investigation of Energetic Particle Distribution from High‐Order Detonations of Munitions. Propellants, Explosives, Pyrotechnics, 42(8), pp. 932-941. [https://doi.org/10.1002/prep.201700089 doi: 10.1002/prep.201700089]</ref>. To ensure that contaminants are monitored and controlled at these sites and to sustainably manage them a variety of sample matrices (surface or groundwater, process waters, soil, and tissues) must be considered. (Process water refers to water used during industrial manufacturing or processing of legacy and insensitive munitions.) Furthermore, additional analytes must be added to existing methodologies as the usage of IM compounds changes and as new degradation compounds are identified. Of note, relatively new IM formulations containing [[Wikipedia: Nitrotriazolone | NTO]], [[Wikipedia: 2,4-Dinitroanisole | DNAN]], and [[Wikipedia: Nitroguanidine | NQ]] are seeing use in [[Wikipedia: IMX-101 | IMX-101]], IMX-104, Pax-21 and Pax-41 (Table 1)<ref>Mainiero, C. 2015. Picatinny Employees Recognized for Insensitive Munitions. U.S. Army, Picatinny Arsenal Public Affairs. [https://www.army.mil/article/148873/picatinny_employees_recognized_for_insensitive_munitions Open Access Press Release]</ref><ref>Frem, D., 2022. A Review on IMX-101 and IMX-104 Melt-Cast Explosives: Insensitive Formulations for the Next-Generation Munition Systems. Propellants, Explosives, Pyrotechnics, 48(1), e202100312. [https://doi.org/10.1002/prep.202100312 doi: 10.1002/prep.202100312]</ref>. | ||

| − | + | Sampling procedures for legacy and insensitive munitions are identical and utilize multi-increment sampling procedures found in USEPA Method 8330B Appendix A<ref name= "8330B"/>. Sample hold times, subsampling and quality control requirements are also unchanged. The key differences lie in the extraction methods and instrumental methods. Briefly, legacy munitions analysis of low concentration waters uses a single cartridge reverse phase [[Wikipedia: Solid-phase extraction | SPE]] procedure, and [[Wikipedia: Acetonitrile | acetonitrile]] (ACN) is used for both extraction and [[Wikipedia: Elution | elution]] for aqueous and solid samples<ref name= "8330B"/><ref>United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), 2007. EPA Method 3535A (SW-846) Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE), Revision 1. [https://www.epa.gov/esam/epa-method-3535a-sw-846-solid-phase-extraction-spe USEPA Website] [[Media: epa-3535a.pdf | Method 3535A.pdf]]</ref>. An [[Wikipedia: High-performance_liquid_chromatography#Isocratic_and_gradient_elution | isocratic]] separation via reversed-phase C-18 column with 50:50 methanol:water mobile phase or a C-8 column with 15:85 isopropanol:water mobile phase is used to separate legacy munitions<ref name= "8330B"/>. While these procedures are sufficient for analysis of legacy munitions, alternative solvents, additional SPE cartridges, and a gradient elution are all required for the combined analysis of legacy and insensitive munitions. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Previously, analysis of legacy and insensitive munitions required multiple analytical techniques, however the methods presented here combine the two munitions categories resulting in an HPLC-UV method and accompanying extraction methods for a variety of common sample matrices. A secondary HPLC-UV method and a HPLC-MS method were also developed as confirmatory methods. The methods discussed in this article were validated extensively by single-blind round robin testing and subsequent statistical treatment as part of ESTCP [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/d05c1982-bbfa-42f8-811d-51b540d7ebda ER19-5078]. Wherever possible, the quality control criteria in the Department of Defense Quality Systems Manual for Environmental Laboratories were adhered to<ref>US Department of Defense and US Department of Energy, 2021. Consolidated Quality Systems Manual (QSM) for Environmental Laboratories, Version 5.4. 387 pages. [https://www.denix.osd.mil/edqw/denix-files/sites/43/2021/10/QSM-Version-5.4-FINAL.pdf Free Download] [[Media: QSM-Version-5.4.pdf | QSM Version 5.4.pdf]]</ref>. Analytes included in the methods presented here are found in Table 1. | |

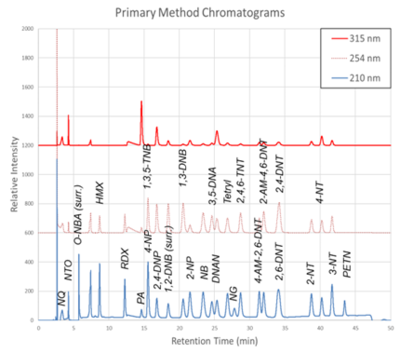

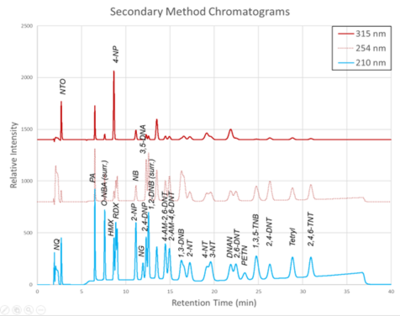

| − | + | The chromatograms produced by the primary and secondary HPLC-UV methods are shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2, respectively. Chromatograms for each detector wavelength used are shown (315, 254, and 210 nm). | |

| − | + | ==Extraction Methods== | |

| + | [[File: ScircleFig3.PNG |thumb|400px|Figure 3. Triple cartridge SPE setup]] | ||

| + | [[File: ScircleFig4.PNG |thumb|400px|Figure 4. A flow chart of the soil extraction procedure]] | ||

| + | ===High Concentration Waters (> 1 ppm)=== | ||

| + | Aqueous samples suspected to contain the compounds of interest at concentrations detectable without any extraction or pre-concentration are suitable for analysis by direct injection. The method deviates from USEPA Method 8330B by adding a pH adjustment and use of MeOH rather than ACN for dilution<ref name= "8330B"/>. The pH adjustment is needed to ensure method accuracy for ionic compounds (like NTO or PA) in basic samples. A solution of 1% HCl/MeOH is added to both acidify and dilute the samples to a final acid concentration of 0.5% (vol/vol) and a final solvent ratio of 1:1 MeOH/H<sub><small>2</small></sub>O. The direct injection samples are then ready for analysis. | ||

| − | + | ===Low Concentration Waters (< 1 ppm)=== | |

| + | Aqueous samples suspected to contain the compounds of interest at low concentrations require extraction and pre-concentration using solid phase extraction (SPE). The SPE setup described here uses a triple cartridge setup shown in Figure 3. Briefly, the extraction procedure loads analytes of interest onto the cartridges in this order: Strata<sup><small>TM</small></sup> X, Strata<sup><small>TM</small></sup> X-A, and Envi-Carb<sup><small>TM</small></sup>. Then the cartridge order is reversed, and analytes are eluted via a two-step elution, resulting in 2 extracts (which are combined prior to analysis). Five milliliters of MeOH is used for the first elution, while 5 mL of acidified MeOH (2% HCl) is used for the second elution. The particular SPE cartridges used are noncritical so long as cartridge chemistries are comparable to those above. | ||

| − | + | {| class="wikitable mw-collapsible" style="float:left; margin-right:20px; text-align:center;" | |

| + | |+Table 2. Primary HPLC-UV mobile phase gradient method concentrations | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | colspan="5" style="background-color:white;"| Method run time = 48 minutes; Column temperature = 25°C<br>Injection volume = 50 μL; Flow rate = 1.0 mL/min<br>Detector wavelengths = 210, 254, and 310 nm | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! Time<br>(min) | ||

| + | ! Reagent Water<br>(%) | ||

| + | ! MeOH<br>(%) | ||

| + | ! 0.1% TFA/Water<br>(%) | ||

| + | ! ACN<br>(%) | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 0.00 || 89 || 3 || 3 || 5 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2.00 || 89 || 3 || 3 || 5 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2.20 || 52 || 40 || 3 || 5 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 12.5 || 52 || 40 || 3 || 5 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 19.0 || 57 ||35 || 3 || 5 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 28.0 || 48 || 44 || 3 || 5 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 32.0 || 48 || 44 || 3 || 5 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 44.0 || 32 || 60 || 3 || 5 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 44.1 || 89 || 3 || 3 || 5 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 48.0 || 89 || 3 || 3 || 5 | ||

| + | |} | ||

| − | + | ===Soils=== | |

| + | Soil collection, storage, drying and grinding procedures are identical to the USEPA Method 8330B procedures<ref name= "8330B"/>; however, the solvent extraction procedure differs in the number of sonication steps, sample mass and solvent used. A flow chart of the soil extraction procedure is shown in Figure 4. Soil masses of approximately 2 g and a sample to solvent ratio of 1:5 (g/mL) are used for soil extraction. The extraction is carried out in a sonication bath chilled below 20 ⁰C and is a two-part extraction, first extracting in MeOH (6 hours) followed by a second sonication in 1:1 MeOH:H<sub><small>2</small></sub>O solution (14 hours). The extracts are centrifuged, and the supernatant is filtered through a 0.45 μm PTFE disk filter. | ||

| − | + | The solvent volume should generally be 10 mL but if different soil masses are required, solvent volume should be 5 mL/g. The extraction results in 2 separate extracts (MeOH and MeOH:H<sub><small>2</small></sub>O) that are combined prior to analysis. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Tissues=== | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Tissue matrices are extracted by 18-hour sonication using a ratio of 1 gram of wet tissue per 5 mL of MeOH. This extraction is performed in a sonication bath chilled below 20 ⁰C and the supernatant (MeOH) is filtered through a 0.45 μm PTFE disk filter. | |

| − | + | Due to the complexity of tissue matrices, an additional tissue cleanup step, adapted from prior research, can be used to reduce interferences<ref name="RussellEtAl2014">Russell, A.L., Seiter, J.M., Coleman, J.G., Winstead, B., Bednar, A.J., 2014. Analysis of munitions constituents in IMX formulations by HPLC and HPLC-MS. Talanta, 128, pp. 524–530. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.talanta.2014.02.013 doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2014.02.013]</ref><ref name="CrouchEtAl2020"/>. The cleanup procedure uses small scale chromatography columns prepared by loading 5 ¾” borosilicate pipettes with 0.2 g activated silica gel (100–200 mesh). The columns are wetted with 1 mL MeOH, which is allowed to fully elute and then discarded prior to loading with 1 mL of extract and collecting in a new amber vial. After the extract is loaded, a 1 mL aliquot of MeOH followed by a 1 mL aliquot of 2% HCL/MeOH is added. This results in a 3 mL silica treated tissue extract. This extract is vortexed and diluted to a final solvent ratio of 1:1 MeOH/H<sub><small>2</small></sub>O before analysis. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ==HPLC-UV and HPLC-MS Methods== |

| − | {| class="wikitable" style="float:right; margin-left: | + | {| class="wikitable mw-collapsible" style="float:left; margin-right:20px; text-align:center;" |

| − | |+ Table | + | |+Table 3. Secondary HPLC-UV mobile phase gradient method concentrations |

| + | |- | ||

| + | | colspan="5" style="background-color:white;" | Method run time = 43 minutes; Column temperature = 25°C<br>Injection volume = 50 μL; Flow rate = 0.8 mL/min<br>Detector wavelengths = 210, 254, and 310 nm | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! Time<br>(min) | ||

| + | ! Reagent Water<br>(%) | ||

| + | ! MeOH<br>(%) | ||

| + | ! 0.1% TFA/Water<br>(%) | ||

| + | ! ACN<br>(%) | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 0.00 || 75 || 10 || 10 || 5 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2.50 || 75 || 10 || 10 || 5 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2.60 || 39 || 46 ||10 || 5 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 9.00 || 39 || 46 ||10 || 5 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 9.10 || 33.5 || 51.5 || 10 || 5 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 15.00 || 35 || 50 || 10 || 5 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 15.10 || 43 || 42 || 10 || 5 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 33.00 || 30 || 55 || 10 || 5 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 33.10 || 75 || 10 || 10 || 5 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 43.00 || 75 || 10 || 10 || 5 | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable mw-collapsible" style="float:right; margin-left:20px; text-align:center;" | ||

| + | |+Table 4. Ionization source and detector parameters | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! Parameter | ||

| + | ! Value | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | Ionization Source || APCI | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | Ionization Mode || Negative | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | Drying Gas Temperature (°C) || 350 |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | Vaporizer Temperature (°C) || 325 |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | | | ||

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | Drying Gas Flow (L/min) || 4.0 |

| + | |- | ||

| + | | Nebulizer Pressure (psig) || 40 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | Corona Current (μA) || 10 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | Capillary Potential (V) || 1500 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | Mass Range || 40 – 400 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | Fragmentor || 100 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | Gain || 1 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | Threshold || 0 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | Step Size || 0.20 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | Speed (μ/sec) || 743 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | Peak Width (min) || 0.06 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | Cycle Time (sec/cycle) || 0.57 | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | The Primary HPLC-UV method uses a Phenomenex Synergi 4 µm Hydro-RP column (80Å, 250 x 4.6 mm), or comparable, and is based on both the HPLC method found in USEPA 8330B and previous work<ref name= "8330B"/><ref name="RussellEtAl2014"/><ref name="CrouchEtAl2020"/>. This separation relies on a reverse phase column and uses a gradient elution, shown in Table 2. Depending on the analyst’s needs and equipment availability, the method has been proven to work with either 0.1% TFA or 0.25% FA (vol/vol) mobile phase. Addition of a guard column like a Phenomenex SecurityGuard AQ C18 pre-column guard cartridge can be optionally used. These optional changes to the method have no impact on the method’s performance. | |

| − | The | + | |

| − | + | The Secondary HPLC-UV method uses a Restek Pinnacle II Biphenyl 5 µm (150 x 4.6 mm) or comparable column and is intended as a confirmatory method. Like the Primary method, this method can use an optional guard column and utilizes a gradient elution, shown in Table 3. | |

| − | + | ||

| + | For instruments equipped with a mass spectrometer (MS), a secondary MS method is available and was developed alongside the Primary UV method. The method was designed for use with a single quadrupole MS equipped with an atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI) source, such as an Agilent 6120B. A majority of the analytes shown in Table 1 are amenable to this MS method, however nitroglycerine (which is covered extensively in USEPA method 8332) and 2-,3-, and 4-nitrotoluene compounds aren’t compatible with the MS method. MS method parameters are shown in Table 4. | ||

| − | + | ==Summary== | |

| + | The extraction methods and instrumental methods in this article build upon prior munitions analytical methods by adding new compounds, combining legacy and insensitive munitions analysis, and expanding usable sample matrices. These methods have been verified through extensive round robin testing and validation, and while the methods are somewhat challenging, they are crucial when simultaneous analysis of both insensitive and legacy munitions is needed. | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | |||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

==See Also== | ==See Also== | ||

| + | *[[Media: ERDC_TR-21-12.pdf | Preparative, Extraction, and Analytical Methods for Simultaneous Determination of Legacy and Insensitive Munition (IM) Constituents in Aqueous, Soil or Sediment, and Tissue Matrices]] | ||

| + | *[https://serdp-estcp.mil/focusareas/9f7a342a-1b13-4ce5-bda0-d7693cf2b82d/uxo#subtopics SERDP/ESTCP Focus Areas – UXO – Munitions Constituents] | ||

| + | *[https://denix.osd.mil/edqw/home/ Environmental Data Quality Workgroup] | ||

Latest revision as of 21:59, 26 September 2024

Sediment Porewater Dialysis Passive Samplers for Inorganics (Peepers)

Sediment porewater dialysis passive samplers, also known as “peepers,” are sampling devices that allow the measurement of dissolved inorganic ions in the porewater of a saturated sediment. Peepers function by allowing freely-dissolved ions in sediment porewater to diffuse across a micro-porous membrane towards water contained in an isolated compartment that has been inserted into sediment. Once retrieved after a deployment period, the resulting sample obtained can provide concentrations of freely-dissolved inorganic constituents in sediment, which provides measurements that can be used for understanding contaminant fate and risk. Peepers can also be used in the same manner in surface water, although this article is focused on the use of peepers in sediment.

Related Article(s):

- Contaminated Sediments - Introduction

- Contaminated Sediment Risk Assessment

- In Situ Treatment of Contaminated Sediments with Activated Carbon

- Passive Sampling of Munitions Constituents

- Sediment Capping

- Mercury in Sediments

- Passive Sampling of Sediments

Contributor(s):

- Florent Risacher, M.Sc.

- Jason Conder, Ph.D.

Key Resource(s):

- A review of peeper passive sampling approaches to measure the availability of inorganics in sediment porewater[1]

- Best Practices User’s Guide: Standardizing Sediment Porewater Passive Samplers for Inorganic Constituents of Concern[2]

Introduction

Biologically available inorganic constituents associated with sediment toxicity can be quantified by measuring the freely-dissolved fraction of contaminants in the porewater[3][4]. Classical sediment porewater analysis usually consists of collecting large volumes of bulk sediments which are then mechanically squeezed or centrifuged to produce a supernatant, or suction of porewater from intact sediment, followed by filtration and collection[5]. The extraction and measurement processes present challenges due to the heterogeneity of sediments, physical disturbance, high reactivity of some complexes, and interaction between the solid and dissolved phases, which can impact the measured concentration of dissolved inorganics[6]. For example, sampling disturbance can affect redox conditions[7][8], which can lead to under or over representation of inorganic chemical concentrations relative to the true dissolved phase concentration in the sediment porewater[9][5].

To address the complications with mechanical porewater sampling, passive sampling approaches for inorganics have been developed to provide a method that has a low impact on the surrounding geochemistry of sediments and sediment porewater, thus enabling more precise measurements of inorganics[4]. Sediment porewater dialysis passive samplers, also known as “peepers,” were developed more than 45 years ago[10] and refinements to the method such as the use of reverse tracers have been made, improving the acceptance of the technology as decision-making tool.

Peeper Designs

Peepers (Figure 1) are inert containers with a small volume (typically 1-100 mL) of purified water (“peeper water”) capped with a semi-permeable membrane. Peepers can be manufactured in a wide variety of formats (Figure 2, Figure 3) and deployed in in various ways.

Two designs are commonly used for peepers. Frequently, the designs are close adaptations of the original multi-chamber Hesslein design[10] (Figure 2), which consists of an acrylic sampler body with multiple sample chambers machined into it. Peeper water inside the chambers is separated from the outside environment by a semi-permeable membrane, which is held in place by a top plate fixed to the sampler body using bolts or screws. An alternative design consists of single-chamber peepers constructed using a single sample vial with a membrane secured over the mouth of the vial, as shown in Figure 3, and applied in Teasdale et al.[7], Serbst et al.[11], Thomas and Arthur[12], Passeport et al.[13], and Risacher et al.[2]. The vial is filled with deionized water, and the membrane is held in place using the vial cap or an o-ring. Individual vials are either directly inserted into sediment or are incorporated into a support structure to allow multiple single-chamber peepers to be deployed at once over a given depth profile (Figure 3).

| Compound | Acronym | CAS Number |

|---|---|---|

| 1,2-Dinitrobenzene (surrogate) | 1,2-DNB (surr.) | 528-29-0 |

| 1,3-Dinitrobenzene | 1,3-DNB | 99-65-0 |

| 1,3,5-Trinitrobenzene | 1,3,5-TNB | 99-35-4 |

| 1,4-Dinitrobenzene | 1,4-DNB (surr.) | 100-25-4 |

| 2-Amino-4,6-dinitrotoluene | 2-Am-4,6-DNT | 35572-78-2 |

| 2-Nitrophenol | 2-NP | 88-75-5 |

| 2-Nitrotoluene | 2-NT | 88-72-2 |

| 2,4-Dinitrophenol | 2,4-DNP | 51-28-5 |

| 2,4-Dinitrotoluene | 2,4-DNT | 121-14-2 |

| 2,4,6-Trinitrophenol | Picric Acid (PA) | 88-89-1 |

| 2,4,6-Trinitrotoluene | 2,4,6-TNT | 118-96-7 |

| 2,6-Dinitrotoluene | 2,6-DNT | 606-20-2 |

| 3-Nitrotoluene | 3-NT | 99-08-1 |

| 3,5-Dinitroaniline | 3,5-DNA | 618-87-1 |

| 4-Amino-2,6-dinitrotoluene | 4-Am-2,6-DNT | 19406-51-0 |

| 4-Nitrophenol | 4-NP | 100-02-7 |

| 4-Nitrotoluene | 4-NT | 99-99-0 |

| 2,4-Dinitroanisole | DNAN | 119-27-7 |

| Octahydro-1,3,5,7-tetranitro-1,3,5,7-tetrazocine | HMX | 2691-41-0 |

| Nitrobenzene | NB | 98-95-3 |

| Nitroglycerine | NG | 55-63-0 |

| Nitroguanidine | NQ | 556-88-7 |

| 3-Nitro-1,2,4-triazol-5-one | NTO | 932-64-9 |

| ortho-Nitrobenzoic acid | o-NBA (surr.) | 552-16-9 |

| Pentaerythritol tetranitrate | PETN | 78-11-5 |

| Hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine | RDX | 121-82-4 |

| N-Methyl-N-(2,4,6-trinitrophenyl)nitramide | Tetryl | 479-45-8 |

| Note: Analytes in bold are not identified by EPA Method 8330B. | ||

The primary intention of the analytical methods presented here is to support the monitoring of legacy and insensitive munitions contamination on test and training ranges, however legacy and insensitive munitions often accompany each other at demilitarization facilities, manufacturing facilities, and other environmental sites. Energetic materials typically appear on ranges as small, solid particulates and due to their varying functional groups and polarities, can partition in various environmental compartments[14]. To ensure that contaminants are monitored and controlled at these sites and to sustainably manage them a variety of sample matrices (surface or groundwater, process waters, soil, and tissues) must be considered. (Process water refers to water used during industrial manufacturing or processing of legacy and insensitive munitions.) Furthermore, additional analytes must be added to existing methodologies as the usage of IM compounds changes and as new degradation compounds are identified. Of note, relatively new IM formulations containing NTO, DNAN, and NQ are seeing use in IMX-101, IMX-104, Pax-21 and Pax-41 (Table 1)[15][16].

Sampling procedures for legacy and insensitive munitions are identical and utilize multi-increment sampling procedures found in USEPA Method 8330B Appendix A[17]. Sample hold times, subsampling and quality control requirements are also unchanged. The key differences lie in the extraction methods and instrumental methods. Briefly, legacy munitions analysis of low concentration waters uses a single cartridge reverse phase SPE procedure, and acetonitrile (ACN) is used for both extraction and elution for aqueous and solid samples[17][18]. An isocratic separation via reversed-phase C-18 column with 50:50 methanol:water mobile phase or a C-8 column with 15:85 isopropanol:water mobile phase is used to separate legacy munitions[17]. While these procedures are sufficient for analysis of legacy munitions, alternative solvents, additional SPE cartridges, and a gradient elution are all required for the combined analysis of legacy and insensitive munitions.

Previously, analysis of legacy and insensitive munitions required multiple analytical techniques, however the methods presented here combine the two munitions categories resulting in an HPLC-UV method and accompanying extraction methods for a variety of common sample matrices. A secondary HPLC-UV method and a HPLC-MS method were also developed as confirmatory methods. The methods discussed in this article were validated extensively by single-blind round robin testing and subsequent statistical treatment as part of ESTCP ER19-5078. Wherever possible, the quality control criteria in the Department of Defense Quality Systems Manual for Environmental Laboratories were adhered to[19]. Analytes included in the methods presented here are found in Table 1.

The chromatograms produced by the primary and secondary HPLC-UV methods are shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2, respectively. Chromatograms for each detector wavelength used are shown (315, 254, and 210 nm).

Extraction Methods

High Concentration Waters (> 1 ppm)

Aqueous samples suspected to contain the compounds of interest at concentrations detectable without any extraction or pre-concentration are suitable for analysis by direct injection. The method deviates from USEPA Method 8330B by adding a pH adjustment and use of MeOH rather than ACN for dilution[17]. The pH adjustment is needed to ensure method accuracy for ionic compounds (like NTO or PA) in basic samples. A solution of 1% HCl/MeOH is added to both acidify and dilute the samples to a final acid concentration of 0.5% (vol/vol) and a final solvent ratio of 1:1 MeOH/H2O. The direct injection samples are then ready for analysis.

Low Concentration Waters (< 1 ppm)

Aqueous samples suspected to contain the compounds of interest at low concentrations require extraction and pre-concentration using solid phase extraction (SPE). The SPE setup described here uses a triple cartridge setup shown in Figure 3. Briefly, the extraction procedure loads analytes of interest onto the cartridges in this order: StrataTM X, StrataTM X-A, and Envi-CarbTM. Then the cartridge order is reversed, and analytes are eluted via a two-step elution, resulting in 2 extracts (which are combined prior to analysis). Five milliliters of MeOH is used for the first elution, while 5 mL of acidified MeOH (2% HCl) is used for the second elution. The particular SPE cartridges used are noncritical so long as cartridge chemistries are comparable to those above.

| Method run time = 48 minutes; Column temperature = 25°C Injection volume = 50 μL; Flow rate = 1.0 mL/min Detector wavelengths = 210, 254, and 310 nm | ||||

| Time (min) |

Reagent Water (%) |

MeOH (%) |

0.1% TFA/Water (%) |

ACN (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.00 | 89 | 3 | 3 | 5 |

| 2.00 | 89 | 3 | 3 | 5 |

| 2.20 | 52 | 40 | 3 | 5 |

| 12.5 | 52 | 40 | 3 | 5 |

| 19.0 | 57 | 35 | 3 | 5 |

| 28.0 | 48 | 44 | 3 | 5 |

| 32.0 | 48 | 44 | 3 | 5 |

| 44.0 | 32 | 60 | 3 | 5 |

| 44.1 | 89 | 3 | 3 | 5 |

| 48.0 | 89 | 3 | 3 | 5 |

Soils

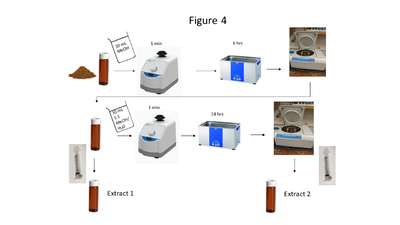

Soil collection, storage, drying and grinding procedures are identical to the USEPA Method 8330B procedures[17]; however, the solvent extraction procedure differs in the number of sonication steps, sample mass and solvent used. A flow chart of the soil extraction procedure is shown in Figure 4. Soil masses of approximately 2 g and a sample to solvent ratio of 1:5 (g/mL) are used for soil extraction. The extraction is carried out in a sonication bath chilled below 20 ⁰C and is a two-part extraction, first extracting in MeOH (6 hours) followed by a second sonication in 1:1 MeOH:H2O solution (14 hours). The extracts are centrifuged, and the supernatant is filtered through a 0.45 μm PTFE disk filter.

The solvent volume should generally be 10 mL but if different soil masses are required, solvent volume should be 5 mL/g. The extraction results in 2 separate extracts (MeOH and MeOH:H2O) that are combined prior to analysis.

Tissues

Tissue matrices are extracted by 18-hour sonication using a ratio of 1 gram of wet tissue per 5 mL of MeOH. This extraction is performed in a sonication bath chilled below 20 ⁰C and the supernatant (MeOH) is filtered through a 0.45 μm PTFE disk filter.

Due to the complexity of tissue matrices, an additional tissue cleanup step, adapted from prior research, can be used to reduce interferences[20][21]. The cleanup procedure uses small scale chromatography columns prepared by loading 5 ¾” borosilicate pipettes with 0.2 g activated silica gel (100–200 mesh). The columns are wetted with 1 mL MeOH, which is allowed to fully elute and then discarded prior to loading with 1 mL of extract and collecting in a new amber vial. After the extract is loaded, a 1 mL aliquot of MeOH followed by a 1 mL aliquot of 2% HCL/MeOH is added. This results in a 3 mL silica treated tissue extract. This extract is vortexed and diluted to a final solvent ratio of 1:1 MeOH/H2O before analysis.

HPLC-UV and HPLC-MS Methods

| Method run time = 43 minutes; Column temperature = 25°C Injection volume = 50 μL; Flow rate = 0.8 mL/min Detector wavelengths = 210, 254, and 310 nm | ||||

| Time (min) |

Reagent Water (%) |

MeOH (%) |

0.1% TFA/Water (%) |

ACN (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.00 | 75 | 10 | 10 | 5 |

| 2.50 | 75 | 10 | 10 | 5 |

| 2.60 | 39 | 46 | 10 | 5 |

| 9.00 | 39 | 46 | 10 | 5 |

| 9.10 | 33.5 | 51.5 | 10 | 5 |

| 15.00 | 35 | 50 | 10 | 5 |

| 15.10 | 43 | 42 | 10 | 5 |

| 33.00 | 30 | 55 | 10 | 5 |

| 33.10 | 75 | 10 | 10 | 5 |

| 43.00 | 75 | 10 | 10 | 5 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Ionization Source | APCI |

| Ionization Mode | Negative |

| Drying Gas Temperature (°C) | 350 |

| Vaporizer Temperature (°C) | 325 |

| Drying Gas Flow (L/min) | 4.0 |

| Nebulizer Pressure (psig) | 40 |

| Corona Current (μA) | 10 |

| Capillary Potential (V) | 1500 |

| Mass Range | 40 – 400 |

| Fragmentor | 100 |

| Gain | 1 |

| Threshold | 0 |

| Step Size | 0.20 |

| Speed (μ/sec) | 743 |

| Peak Width (min) | 0.06 |

| Cycle Time (sec/cycle) | 0.57 |

The Primary HPLC-UV method uses a Phenomenex Synergi 4 µm Hydro-RP column (80Å, 250 x 4.6 mm), or comparable, and is based on both the HPLC method found in USEPA 8330B and previous work[17][20][21]. This separation relies on a reverse phase column and uses a gradient elution, shown in Table 2. Depending on the analyst’s needs and equipment availability, the method has been proven to work with either 0.1% TFA or 0.25% FA (vol/vol) mobile phase. Addition of a guard column like a Phenomenex SecurityGuard AQ C18 pre-column guard cartridge can be optionally used. These optional changes to the method have no impact on the method’s performance.

The Secondary HPLC-UV method uses a Restek Pinnacle II Biphenyl 5 µm (150 x 4.6 mm) or comparable column and is intended as a confirmatory method. Like the Primary method, this method can use an optional guard column and utilizes a gradient elution, shown in Table 3.

For instruments equipped with a mass spectrometer (MS), a secondary MS method is available and was developed alongside the Primary UV method. The method was designed for use with a single quadrupole MS equipped with an atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI) source, such as an Agilent 6120B. A majority of the analytes shown in Table 1 are amenable to this MS method, however nitroglycerine (which is covered extensively in USEPA method 8332) and 2-,3-, and 4-nitrotoluene compounds aren’t compatible with the MS method. MS method parameters are shown in Table 4.

Summary

The extraction methods and instrumental methods in this article build upon prior munitions analytical methods by adding new compounds, combining legacy and insensitive munitions analysis, and expanding usable sample matrices. These methods have been verified through extensive round robin testing and validation, and while the methods are somewhat challenging, they are crucial when simultaneous analysis of both insensitive and legacy munitions is needed.

References

- ^ Risacher, F.F., Schneider, H., Drygiannaki, I., Conder, J., Pautler, B.G., and Jackson, A.W., 2023. A Review of Peeper Passive Sampling Approaches to Measure the Availability of Inorganics in Sediment Porewater. Environmental Pollution, 328, Article 121581. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2023.121581 Open Access Manuscript

- ^ 2.0 2.1 Risacher, F.F., Nichols, E., Schneider, H., Lawrence, M., Conder, J., Sweett, A., Pautler, B.G., Jackson, W.A., Rosen, G., 2023b. Best Practices User’s Guide: Standardizing Sediment Porewater Passive Samplers for Inorganic Constituents of Concern, ESTCP ER20-5261. Project Website Report.pdf

- ^ Conder, J.M., Fuchsman, P.C., Grover, M.M., Magar, V.S., Henning, M.H., 2015. Critical review of mercury SQVs for the protection of benthic invertebrates. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 34(1), pp. 6-21. doi: 10.1002/etc.2769 Open Access Article

- ^ 4.0 4.1 Cleveland, D., Brumbaugh, W.G., MacDonald, D.D., 2017. A comparison of four porewater sampling methods for metal mixtures and dissolved organic carbon and the implications for sediment toxicity evaluations. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 36(11), pp. 2906-2915. doi: 10.1002/etc.3884

- ^ 5.0 5.1 Gruzalski, J.G., Markwiese, J.T., Carriker, N.E., Rogers, W.J., Vitale, R.J., Thal, D.I., 2016. Pore Water Collection, Analysis and Evolution: The Need for Standardization. In: Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, Vol. 237, pp. 37–51. Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-23573-8_2

- ^ Peijnenburg, W.J.G.M., Teasdale, P.R., Reible, D., Mondon, J., Bennett, W.W., Campbell, P.G.C., 2014. Passive Sampling Methods for Contaminated Sediments: State of the Science for Metals. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management, 10(2), pp. 179–196. doi: 10.1002/ieam.1502 Open Access Article

- ^ 7.0 7.1 Teasdale, P.R., Batley, G.E., Apte, S.C., Webster, I.T., 1995. Pore water sampling with sediment peepers. Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 14(6), pp. 250–256. doi: 10.1016/0165-9936(95)91617-2

- ^ Schroeder, H., Duester, L., Fabricius, A.L., Ecker, D., Breitung, V., Ternes, T.A., 2020. Sediment water (interface) mobility of metal(loid)s and nutrients under undisturbed conditions and during resuspension. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 394, Article 122543. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122543 Open Access Article

- ^ Wise, D.E., 2009. Sampling techniques for sediment pore water in evaluation of reactive capping efficacy. Master of Science Thesis. University of New Hampshire Scholars’ Repository. 178 pages. Website Report.pdf

- ^ 10.0 10.1 Hesslein, R.H., 1976. An in situ sampler for close interval pore water studies. Limnology and Oceanography, 21(6), pp. 912-914. doi: 10.4319/lo.1976.21.6.0912 Open Access Article

- ^ Serbst, J.R., Burgess, R.M., Kuhn, A., Edwards, P.A., Cantwell, M.G., Pelletier, M.C., Berry, W.J., 2003. Precision of dialysis (peeper) sampling of cadmium in marine sediment interstitial water. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 45(3), pp. 297–305. doi: 10.1007/s00244-003-0114-5

- ^ Thomas, B., Arthur, M.A., 2010. Correcting porewater concentration measurements from peepers: Application of a reverse tracer. Limnology and Oceanography: Methods, 8(8), pp. 403–413. doi: 10.4319/lom.2010.8.403 Open Access Article

- ^ Passeport, E., Landis, R., Lacrampe-Couloume, G., Lutz, E.J., Erin Mack, E., West, K., Morgan, S., Lollar, B.S., 2016. Sediment Monitored Natural Recovery Evidenced by Compound Specific Isotope Analysis and High-Resolution Pore Water Sampling. Environmental Science and Technology, 50(22), pp. 12197–12204. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b02961

- ^ Walsh, M.R., Temple, T., Bigl, M.F., Tshabalala, S.F., Mai, N. and Ladyman, M., 2017. Investigation of Energetic Particle Distribution from High‐Order Detonations of Munitions. Propellants, Explosives, Pyrotechnics, 42(8), pp. 932-941. doi: 10.1002/prep.201700089

- ^ Mainiero, C. 2015. Picatinny Employees Recognized for Insensitive Munitions. U.S. Army, Picatinny Arsenal Public Affairs. Open Access Press Release

- ^ Frem, D., 2022. A Review on IMX-101 and IMX-104 Melt-Cast Explosives: Insensitive Formulations for the Next-Generation Munition Systems. Propellants, Explosives, Pyrotechnics, 48(1), e202100312. doi: 10.1002/prep.202100312

- ^ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named8330B - ^ United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), 2007. EPA Method 3535A (SW-846) Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE), Revision 1. USEPA Website Method 3535A.pdf

- ^ US Department of Defense and US Department of Energy, 2021. Consolidated Quality Systems Manual (QSM) for Environmental Laboratories, Version 5.4. 387 pages. Free Download QSM Version 5.4.pdf

- ^ 20.0 20.1 Russell, A.L., Seiter, J.M., Coleman, J.G., Winstead, B., Bednar, A.J., 2014. Analysis of munitions constituents in IMX formulations by HPLC and HPLC-MS. Talanta, 128, pp. 524–530. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2014.02.013

- ^ 21.0 21.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedCrouchEtAl2020